I’M TURNING sixty this month and, yes, it sounds old. It’s not that I feel that old, but in sixty years I’ve done a lot and lived a full life. I spent about twenty years of my adult professional life as an actor, and it’s still in my blood. So, for my sixtieth year, I decided to challenge myself and write, produce, and perform a one-man show about my life.

Yes, it’s the height of an ego-driven vanity project—I fully acknowledge and embrace that. Normally, my Scandinavian modesty would have precluded such a venture into egoism. But these are extraordinary times. And if we’ve learned anything from a year and a half of pandemic uncertainty, it’s that we have to embrace today like never before.

So, I’ve spent the last eight months mining the important moments of my life like an archeologist on a dig, gently removing pieces of some ancient artifact—a small piece of pottery, a buried scroll—dusting them off, and then putting them back together to tell a story. In the process of this dig, I’ve uncovered long-lost memories that remind me that my life has been kind of amazing.

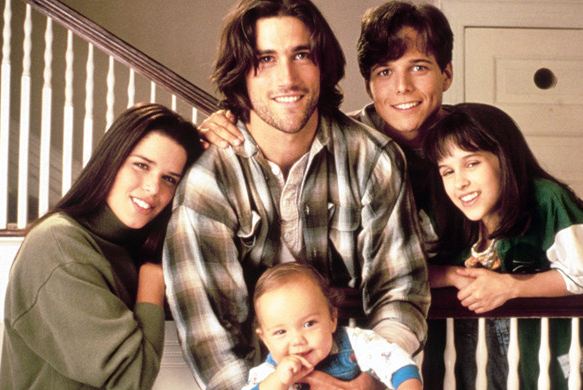

In 1994, I was cast in the pilot episode of a heartfelt family drama on the relatively new FOX TV network. The show, Party of Five, about a family of five children orphaned when their parents died in a car crash, was beautifully written, and I was thrilled to get the small role of Ross, Claudia’s violin teacher. Truthfully, it was just two scenes in the pilot. But they were nice little scenes, and I really was happy to be part of the show. As it turned out, my work on the series would change my life.

At that time, I was a working actor, maybe even a minor celebrity, spending about ten years in television and film. I was lucky enough to work steadily throughout my twenties and early thirties, enough to support myself and even buy a house. But the life of an actor is naturally tenuous, and even more so for me on account of being gay.

Back then, if you were gay in show business, you were pretty much told to shut up about it. “Live your life,” they would say. “Just don’t make a big deal out of it.” And that’s what I and most of my gay actor friends did. We played by the rules and were rewarded with enough work to keep us going—most of the time.

During this time, the 1990s, people all around us were dying of AIDS. It became increasingly important for everyone to come out of the closet so that our collective visibility would force the government to help. Figuring out how to live both in and out of the closet was the central conflict of my life.

Party of Five was picked up for a whole season, and I was asked to continue teaching Claudia violin once every few episodes. I was happy they included me as they went into the full story. While it wasn’t a true hit in terms of ratings, the press loved the show, and we had a small but vocal fan base. The show won the Golden Globe for Best Television Drama in its first year, and ended up having a six-year run (until 2000). Halfway through the first season, I got a call from the producers asking me to come to their office for a “chat.” I was sure they were going to fire me. Instead, they told me they had decided to have my character Ross come out of the closet! I took a deep breath, thanked them for the amazing opportunity, and went home. And then sort of freaked out.

Suddenly, my art was imitating my life, and I was in new and uncharted territory. I had always believed that my sexuality wasn’t important in the roles I played. But I think that’s because I always played straight guys. It never occurred to me that it could be any other way. Now I was given the opportunity to bring a part of me to work that I had always left at home. You would have thought that prospect was gravely frightening. But as it turns out, it was incredibly freeing. Suddenly I wasn’t hiding behind a mask, and I got to really “show up.”

With this newfound confidence, I wrote a letter to the producers describing a storyline I was interested in pursuing. This was completely out of character for me. I had never had the confidence to take my ideas into the writers’ room. But now, for the first time in my life, I felt like I had a voice in the direction I wanted my character to go.

The show was all about defining family: what forms can it take when it’s not typical? The Salinger family, after losing their parents, did everything they could to stay together. With love, they were able to forge a new way. I think that’s why the show struck a chord with so many people and continues to have a cult following.

Ross, a young, single gay man in 1990s San Francisco, was in a sense on the same journey as the Salingers—to find his family. I suggested to the writers that exploring the adoption process and Ross’ desire to start a family might be interesting. They listened and apparently liked the idea, because the last show of the first season was exactly that. The script they wrote was beautiful and turned out to be about a couple of themes. Yes, it was about Ross, a gay man, taking the step to adopt and fall in love with a baby. But it was also about Bailey, one of the Salinger boys, learning to love again after the pain of loss by watching Ross give his heart over to his newborn daughter. The episode was classic Party of Five: well-written, meaningful, and moving.

I had sort of forgotten about this part of my life story. There were bigger milestones that came later: coming out at the glaad Media Awards (1996), meeting and marrying my husband, starting a second career as a restaurateur and chef. How lucky that I’ve been given this time to dig into my earlier life and uncover this artifact from a long-lost world.

Mitchell Anderson is known for his work on Party of Five, Doogie Howser, The Karen Carpenter Story, and, more recently, the Emmy-winning digital series After Forever. He is an Atlanta chef and owner of MetroFresh Café. In November he’ll perform his cabaret You Better Call Your Mother at Atlanta’s Synchronicity Theatre.