WHEN JESÚS announced he’d invited Christopher Isherwood’s longtime lover, Don Bachardy, over for dinner, he acted as if he was daring me not to know my gay history.

Twelve years my senior, Jesús often patronized me. However, this time I countered: “I totally know who Isherwood is! I played the Master of Ceremonies in my high school production of Cabaret.” Unimpressed, he leapt to grill me on some requisite facts in anticipation of our upcoming petite soirée: “Babes, how can you be clueless about Chris and Don’s relationship or that Don’s a recognized portrait artist? Are you even aware Chris passed away?”

While at his former job as an Auto Club dispatcher, Jesús had met Chris and Don six months earlier, on one rare stormy night in L.A. when AAA was swamped with service calls. After he confirmed that the member on the other end of the line was the Christopher Isherwood, Jesús promptly placed the author at the top of the list, saving the stranded couple several hours of a wet waiting. In appreciation, Don invited Jesús, a struggling Chicano artist, to his next opening, and the friendships developed from there.

Don arrived late to Jesús’ West Hollywood apartment that evening, because he’d gotten into a fender bender on the way over. In my estimation, Don was frazzled beyond all reasonable measure over this minor accident. He kept repeating that he absolutely couldn’t function until he had a glass of Absolut in his hand. But since Jesús’ roommates were both recovering alcoholics, there wasn’t any hooch to be had in the house. So Jesús drove right over to Mayfair market to get our little graying guest a big bottle of Grey Goose.

Don eventually calmed down as he sipped his drink. Jesús asked him how he was doing as a single man, and Don let his emotions pour forth. He concluded his lamentations by revealing that this was the first time he’d opened up to anyone about Chris’ death. Maybe that car crash (and cocktail) was just what Don needed to finally express his feelings about the end one of the most famous romantic gay relationships of modern times.

In order to cope with his overwhelming loneliness and loss, Don had begun reading the volumes of daily diary entries Isherwood had been composing for as long as Don could remember. But Don wasn’t reading these journals in chronological order. He was reading them backwards, beginning with the very last entry Chris wrote on the morning of the day he passed. Don was heartened to discover that Chris often wrote directly to him in his private journals, with the author sagely predicting the love of his life would one day need to “hear” his darling’s voice once more.

At 21, I was only six months into my very first relationship, and I regularly vacillated between feeling inferior and adored. I thought: “Jesús best never read any of my uncensored nightly diary entries, whether I’m living or deceased, especially those parts where my angry, wounded words are directed at him.

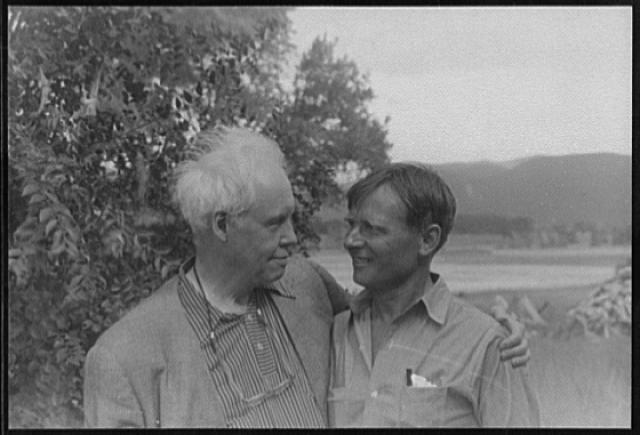

As Jesús battered and deep-fried our dinner, Don happily provided me with the backstory Jesús and the gay literati already well knew: Don had met Chris on the gay beach in Santa Monica on Valentine’s Day, when he was eighteen and Chris was 48. Despite their considerable age difference, the lovers remained together for 33 years. “Maybe there’s hope for me and Jesús,” I mused.

Don partly credited their relationship’s longevity to Chris’ wisdom. At the beginning of their May-December romance, Chris insisted on an open relationship. He firmly believed this was the only way two men, especially so far apart in age, could remain together.

Although Don ended up not eating a bite of the tempura feast Jesús had fixed, he confided in me with a tipsy wink: “When I was a tempting chicken like you, Wynward, I possessed quite a healthy appetite.”

This middle-aged man I’d just met looked nothing like the gap-toothed doll in early photos of him, so I’m sure young Don had no problem finding the boys—and the booze. What I found slightly curious was his British accent, even though Don was born and raised in L.A.

I suspected Jesús that had arranged that dinner with Don not merely “to look at art,” as he so pretentiously put it, because soon afterward he suggested that we have an open relationship, too. As Jesús explained it, his grand and worldly gesture would grant me access to the same youthful exploits he’d voraciously partaken of in the ’70s, and sowing my oats now would hopefully prevent me from straying several years down the road. Flings would only be anonymous safe sex, of course, and we’d remain a committed couple. Of course, Jesús casually added, if I had the freedom to dally, then he could too—which I swiftly discerned was what he was after all along. That and Don’s artistic approval, and perhaps his patronage.

I still don’t know how I feel about the merits of monogamy, but I knew even then that an open relationship wasn’t for me; it’s just not who I am. Plus, Chris and Don’s arrangement wasn’t as blissfully progressive as I was led to believe; jealousies over each other’s affairs almost destroyed their union, and nearly losing Don was the impetus for Isherwood’s novel about a man coping with the death of his lover in A Single Man.

A few months later, I posed nude for Don in his art studio one August afternoon, on what would have been Chris’ 82nd birthday. I was honored that Don chose to celebrate that day with me. As I struggled to sit still, Don remarked from behind his easel that he liked my legs. “Chris and I were leg men,” he asserted gleefully. When he completed the painting, he had me sign and date it, as he does with all the subjects who sit for his portraits.

Jesús, with me now on his arm, continued to be a guest in the eclectic Isherwood-Bachardy bungalow on Adelaide Dr. in the Pacific Palisades. Unfortunately, Jesús got custody of that friend in our divorce six years later, while I got a twinge of schadenfreude from Don’s politely noncommittal response to Jesús’ paintings, which were hanging on his apartment wall that indelible spring evening in 1986.

Wynward H. Oliver is a writer and retired educator living in Los Angeles with his husband of twenty-six years and their two adorable doggies. His memoir, Playing with Myself: The Meanderings of a Mind and a Man in the Making, is nearing completion. You can contact Wyn via email at hextor@att.net. For more stories, visit Wyn’s blog PlayingWithMyselfBlog.

Discussion1 Comment

The review of Cather’s book was Outstanding. I sorta claim her as a sister in crime because she died on the day I was born. I have several of her books and books about her and I have visited Red Cloud, NE. I like Holleran taking a run at her sexuality winch other writers, write around..

I just wanted to say: well done Andrew Holleran, well done Gay & Lesbian Review.