SOUTHWEST VIRGINIA, a rural part of the state nestled in the Appalachian Mountains, probably doesn’t spring to mind when most people think of areas with large LGBT communities. In fact, it’s better known for its outdoor recreational activities and bluegrass music than it is for diversity. Nevertheless a strong and vibrant LGBT community has called Appalachia home for decades.

A small group of dedicated individuals in Roanoke, the region’s cultural hub, has been working to document and spread the word about the community since coming together at the city’s diversity center in 2015. Housed at Roanoke College, the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project is led by Dr. Gregory Samantha Rosenthal with the purpose of “researching and telling the stories of LGBT individuals and organizations” throughout the region.

Since forming, the project has launched a regional archive of LGBT historical materials, creating an oral history collection, three walking tours, multiple online exhibits, interactive theatre workshops, reenactments of gay historical events, a podcast, and multiple Zines.

The most recent digital exhibit, BLT: Bisexual, Lesbian, and Transgender Inclusion and Exclusion in Southwest Virginia, 1990-1995, debuted at the end of 2020.

“Virginia has not always been at the forefront of progressive thinking about LGBT rights. Even today members of the LGBT community are struggling to have their needs met by the state and to have their lives mean as much as those of cisgender straight white men,” Megan Reynolds, an undergraduate research fellow with the project, writes in the introduction of the exhibit.

Records of what bisexual, lesbian, and transgender life was like in Southwest Virginia between 1990 and 1995 are scarce, except for two newsletters written for and by members of the community that are featured prominently in the exhibit.

“These newsletters from the 1980s and 1990s were the way the gay community received information on what was happening in the bigger picture for their representation and rights,” Reynolds explains in reference to Blue Ridge Lambda Press and Skip Two Periods.

Rosenthal notes that bisexual, lesbian, and transgender community members started to become more visible in the two newsletters during the years the exhibit examines. “One of the things we noticed in the newsletters about the time period was that it was a time of new conflict, division, and unity within the community,” she explains.

Although both newsletters started publishing in 1983, it wasn’t until the ‘90s that the words “bisexual” and “transgender” appeared. In the May-June 1991 edition of Blue Ridge Lambda Press, the word “bisexual” first appeared. Additionally, it wasn’t until the March-April 1993 edition that the same newsletter printed the word “transgender.”

Other examples of increased inclusion in the exhibit include an oral history from Peggy Shifflett, a local lesbian. Shifflett discusses First Friday, a lesbian organization in Roanoke in the 1980s, and how it held inclusive meetings which members of various social classes would attend.

Similarly Virginia Lindsey, a transgender woman, explains that the members of the first transgender organization she knew of in Southwest Virginia were accepting of all involved.

Despite some progress related to the inclusion of previously neglected members of the community, oral histories in the exhibit speak to the fact that there was still a significant amount of exclusion and stigma at the time.

Schifflett also explains she felt excluded from her own family because of her lesbian identity. When she attempted to come out to her sister, she says, her sister refused to hear her out and acknowledge her gayness.

Even the very first edition of Skip Two Periods spoke to the sense of isolation that lesbians felt at the time. The editors wrote, “Lack of communication, isolation, retreating into the closet, and diminished self-esteem often become a damaging chain of events for lesbians.” That sense of exclusion led to many discussions in the newsletter over whether they should join the larger gay community to obtain acceptance or move forward alone with a separatist agenda.

Reynolds explains, “Though this may seem as a step backwards for the lesbian community, working on their own agenda was the most important incentive for them and helped them become a strong part of the LGBT community of today.”

For bisexual individuals, the exclusion they experienced from some lesbian organizations led to the increased use of the term “bisexual erasure.” Reynolds notes in the exhibit that the lesbians who were in favor of excluding bisexuals “didn’t appreciate women who they thought were only sometimes lesbian but also romantically or sexually involved with men.” She goes on to say that such ignorant views at the time were perpetuated by the thought that one’s sexuality was dictated by the gender identity of the person with whom they were presently in a relationship, which discounted the fact that sexuality presents on a spectrum.

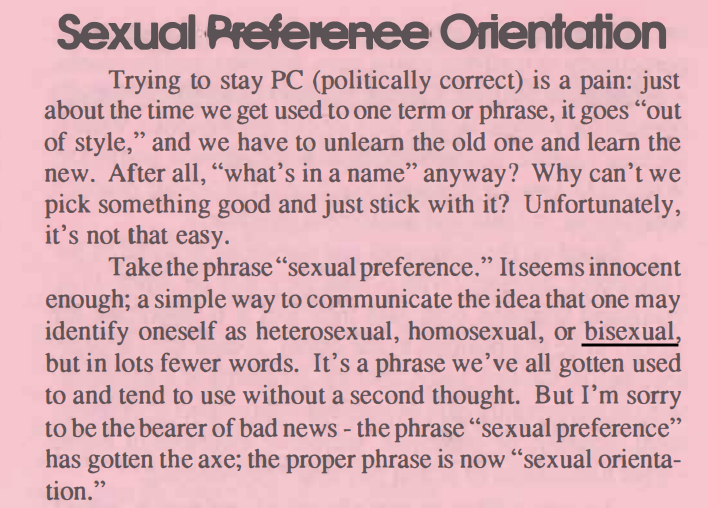

It was in reference to more inclusive terminology that a writer in the May-June 1991 edition of Blue Ridge Lambda Press used in his argument against political correctness when it comes to self-identification by saying, “Trying to stay PC is a pain: just about the time we get used to one term or phrase, it goes ‘out of style,’ and we have to unlearn the old one and learn the new. After all, ‘what’s in a name’ anyway? Why can’t we pick something good and just stick with it? Unfortunately, it’s not that easy.”

As a result of such exclusionary viewpoints, many women at the time who actually identified as bisexual would refer to themselves as being lesbian at lesbian gatherings, Nancy Kelly notes in an oral history. Reynolds says they did so “to be included without any problems and to not be excluded by lesbian separatists.”

Transgender individuals experienced even more severe erasure. Reynolds explains, “As the Blue Ridge Lambda Press was written and published by gay men, there is often a seeming ignorance of what transgender communities were doing in Southwest Virginia at the time.”

One of the oral histories notes that the level of exclusion for certain members of the transgender community was so extreme that one woman wasn’t even allowed to use the restroom on the floor in which she worked. Instead, she had to go to an entirely different floor just to find a family restroom.

At the end of the exhibit, Reynolds writes, “Bisexual, lesbian, and transgender individuals being fully accepted as part of the gay community in the 1990s was just the beginning of this expansion of the queer community to include everyone, no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity.”

She says she hopes those who view the exhibit will come away from it with an understanding that the history of the LGBT community is more expansive than just what is included in history books. “Providing this history that has been hidden up until now for the most part helps people to view LGBT people with a different perspective and be more accepting,” she notes.

Aila Alvina Boyd is a Virginia-based writer, educator, and award-winning journalist.

Aila Alvina Boyd is a Virginia-based writer, educator, and award-winning journalist.