MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS have passed, and even though we were together for a mere ten hours, he made a mark on my life as singular as a thumbprint.

Jonas and I met at a gay club in Paris. It was 1990. He was a 38-year-old Swede on vacation. I was a Filipino writer who had moved from Boston with an English degree, in search of a story. I was 23 and toward the end of a year-long stay. We were in the club basement, which provided cubicles for carnal interludes. In jeans and a collarless gray T-shirt, Jonas stood in a lit corner with arms folded. He was tan and tall with wavy dark hair and the kind of physique that had fueled many an adolescent fantasy. But it was the smile that got me. Grand and warm, Jonas’ smile neutralized my stifling insecurity that physically I could be no match. Athletic build notwithstanding, I was still a boy, a work in progress. I approached him. He might have said something—his name, a greeting. We huddled into a cubicle.

Because men of Jonas’ stature usually overlooked me, I doubted the night could get any better. But it did.

“I wonder about you,” he said in English. We were now on the metro, headed to where he was staying. “It’s not always I meet someone right after he’s had someone else.” I could only smirk.

The ease with which Jonas spoke allowed for a fluid conversation. He was an oncologist who skied and lifted weights, bet on horses, and was hooked on European football. He had gone to boarding school, where homosexuality was so rampant that he thought it was the norm and was therefore shocked at his mother’s initial coldness when he came out. For his sojourn in Paris, he was staying at a friend’s place.

I confided that while I was out to some friends, I was closeted with my family. I asked about any boyfriend in his life, and he replied that he had, but: “We’re no longer together, but I still love him. I’m helping him through psychological problems. He’s actually not my type.” I didn’t ask Jonas what exactly his type was or if he had ever been with an Asian before. We were enjoying each other’s company too much; I didn’t care.

I went home with him to a townhouse in the Place des Vosges, once the address of such historical figures as Cardinal Richelieu and Victor Hugo. Enormous windows afforded a view of vaulted arcades and brick façades surrounding a statue of Louis XIII astride a stallion. We ensconced ourselves in a dim room on a king-size bed and under sheets fluffy as an avalanche of marshmallows, our bodies in synch like notes to music.

“Is that my heart beating?” he asked at dawn to the rattle of a drain pipe. And then, “I like you a lot.”

“I like you a lot, too,” I said.

But he was going back to Sweden in two days, and I was moving to San Francisco in two weeks. Come sunrise, he gave me his address. I promised to write.

I kept my word, initiating a two-year postal relationship. Jonas wrote of the freezing Stockholm winters, his former lover’s alcoholism, and the spring sunshine. He divulged his HIV-positive status, painted me flowers, and assured me that he would never forget our night. He told me he loved me. I told Jonas of my adventures in discovering my gay identity.

Once in San Francisco, I quickly realized that I was a flavor, one that appealed to men who lusted primarily for Asians. Bars existed as designated venues for specific ethnicities and their admirers: the N-Touch for Asians and Pacific Islanders, Esta Noche for Latinos, the Pendulum for Blacks. Meanwhile, white gay men stuck together in their own bars from the Castro to the South of Market and all the way up to Pacific Heights. Labels had been created to identify those who fixate on a certain race: “Rice Queen,” “Bean Queen,” “Chocolate Queen,” and “Potato Queen.”

To expand my appeal, I lifted weights to attain the coveted physique of the all-American jock. Every weekend, I sought to relive the spark I had found with Jonas, with whom connecting had been so easy, so instantaneous. However, what San Francisco was teaching me about the convoluted correlation between race and sex reduced all prospects of love to the color of my skin.

Jonas wrote to me for the last time in the winter of 1992. Alas, he would succumb to the disease that had claimed a swath of other gay men of his generation. As for me, I proceeded in the ensuing three decades to ride a rollercoaster of bliss and heartache. I would come out to family and all would be well, have one-night stands that would flourish into everlasting friendships, and hook up with guys that appeared to have jumped out of a porn flick and into my bedroom, leaving me perplexed as to why their passion could not survive the sunrise.

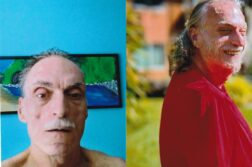

Through all this, the issue of race has become increasingly inconsequential. My motto: either a man will love me or he won’t. Best not to be analytical over affairs of the heart. I am now 54, in the autumn of my years. Sometimes, I have wondered what might have been had Jonas survived. But we can only control our life course up to a point. After that, we need to trust in fate, which decided that he and I were meant for one perfect night only, a night that still inspires every love story that I write.

Rafaelito V. Sy did write and publish a novel, titled Potato Queen (Palari Publishing) in 2005. Today he maintains a lively blog at www.rafsy.com.