Roberto Juarez: Crossing Five Decades

(Works Created Between 1983 and 2023)

C. Parker Gallery

Feb. 28, 2023 – Apr. 15, 2024

Roberto Juarez (b. 1952) is a multi-faceted and tri-cultural artist. His work includes painting and drawing as well as numerous public murals for such venues as the dome of the School of Engineering at the University of Michigan, the Miami Airport, and Grand Central Station in New York. His mother was Puerto Rican and his father was from Mexico (the place with which he most directly identifies as a “patria” or homeland). Roberto was born in Chicago and studied film in San Francisco, later spending time in both Miami and Rome. But since the late 1970s, New York has been his home base. The magnet for him was the Downtown cultural scene of the 1980s; much of the energy and vivacity in his paintings and drawings may be traced to that time period. Roberto’s immediate cohort included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Arch Connelly, Mark Tambella, Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, Jimmy Wright, Elaine Reichek, and others. All of them took great liberties with the characteristics of movements like international Neo Expressionism (called the Trans-Avantgarde in Italy and, in Germany, the Neue Wilden or New Fauves) and pattern and decoration styles that impacted their art. Many of the male members, including Juarez, were queer and manifested a distinct and often highly idiosyncratic as well as a socially engaged approach to sexuality.

Juarez has had a sequence of exhibitions in the past two years in both the U.S. and abroad. Two of them were in Italy, where he had never had a gallery before. In December 2023 the Apalazzo Gallery in Brescia presented a retrospective of paintings on paper from the 1980s, organized by the opera and theatre impresario Fabio Cherstich who was also responsible for a pop-up, week-long show this past April at the eighteenth-century Palazzo Tiepolo in Venice, coinciding with the opening of the Venice Biennale. They both concentrated on his work of the 1980s and its relationship to the visual production of his fellow artists within the circle of the East Village avant garde. Meanwhile in the States, Roberto exhibited his most recent works during the summer of last year at Time and Space Ltd., a cultural center in Hudson, New York, an upstate hipster-heaven. And finally, the C. Parker Gallery in Greenwich, Ct. staged a mini retrospective of the artist’s work in a judiciously chosen and tastefully installed show of nearly five decades of his art.

The C. Parker Gallery show contained one example of Roberto’s 1980s work that possessed his characteristic nervous, sensuous, and frenzied brushwork, luxurious use of brightly colored tones, and sensitivity to such long-cherished sources as Van Gogh’s yellows and reds. Other 1980s works are more heavily invested in an intense testimonial of sexuality that characterized Juarez’s Downtown, Lower East Side aesthetic. The Brescia exhibition, however, concentrated specifically on this side of the artist’s work.

The 1980s paintings on paper were something of a “rediscovery” for Roberto. Virtually none of which had sold when he painted them, and dozens of these pieces remained in deep storage in his studio until the pandemic, when Juarez had time to take a census of his previous works. It was then that he rediscovered the 1984 “Phone Sex” among other similar works redolent of themes directly related to the scourge of HIV/AIDS that ravaged the LGBTQIA+ community.

In “Phone Sex” we observe a man dressed in red – the color of passion, desire and inflamed sexual hunger – sitting on a chair or a couch, his tiny feet dangling below him. The central character of this intimate, even lonely drama, exists only within his own universe of yearning and craving contact with another hidden human being. His facial features are indistinct and mask life, reminding us of the artist’s fascination with and use of motifs suggested by ancient Mexican or Peruvian ceramics. At the lower right there is a huge green rotary telephone. Four bells indicate the sound of the ringing. The protagonist fondles his immense phallus protruding from a large opening in his pants. His right hand holds his erect penis while his left-hand strokes it in what is certainly increasingly urgent caresses. His orgasm is near; the culmination of an act – or a performance of lust – that forms the core of this image. While the phone’s receiver is connected to the body of the machine, there is a distinct intimation that the protagonist is not alone. He is accompanied by a voice at the other end of the line. This disembodied voice represents, in fact, another participant in the scene: a sonic aura without a concrete physical presence. As Roberto stated to a group of my graduate students when I took them to visit his East 8th Street studio, “During the AIDS crisis phone sex was virtually the only secure way of connecting with other gay men.”

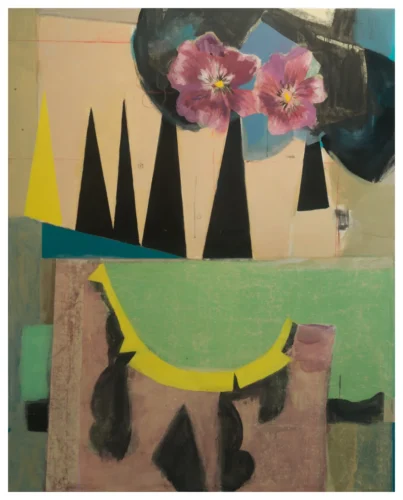

In 2018 I had the privilege of curating an exhibition of ten years of Roberto’s work at the Boulder Colorado Museum of Contemporary Art titled “Roberto Juarez: Processing” and which contained art in a variety of media, from paintings, drawings, and collages to studies for mural commissions. The word “processing” partly referred to the artist’s dealing with the emotional impact of the death of his father – also named Roberto. Although none of the works within this group were representational, all of them evinced a decidedly somber mood, including the mixed media on canvas “Pater Painting” (2017). This piece, with its combination of lyrical floral elements juxtaposed with a series of spiky black forms and quasi-architectonic shapes, elicited from the viewer a sense of melancholic nostalgia. As such it served as one of the signature pieces in both the Boulder and the Greenwich exhibitions.

The mixed media on linen painting called “Tablet” from 2015 (also in the Greenwich exhibition) attests to the artist’s interest in fragmentation and manipulation of space. Evoking a tabletop still life, Juarez seemingly stitches together elements derived from both soft and solid shapes. With an elusive recognition of Cubist form, the components of “Tablet” remind us of a way of seeing objects within space that is a mixture of quasi-geometric form within a background of washes of color. Here and there are hints of fabrics such as lace, interspersed with paper cutouts. A sense of recognition coexists with a disorientation of space.

This work shows Roberto Juarez within his most experimental and creatively cerebral visual habitat. His evolving imagination, spanning interest in natural forms, experimental with pure abstraction, and sensitivity to Juarez’s site specific projects, reveals an immensely multi-faceted artist rooted in Latinx and queer sensibilities, but tethered to no single guiding aesthetic force. The Greenwich show is the closest thing to a full-dress anthology of Juarez’s painting; and it makes us anxious to experience a much more fleshed-out museum exhibition that should span the same time frame.

Edward J. Sullivan is an art historian and a curator who teaches at New York University (NYU). He writes about Latin American, Latino and Latinx art and artists from the 19th century to today. His next book, a memoir entitled Latino New York 1970-2001: Art & Experience, will be published next year by Yale University Press.

Edward J. Sullivan is an art historian and a curator who teaches at New York University (NYU). He writes about Latin American, Latino and Latinx art and artists from the 19th century to today. His next book, a memoir entitled Latino New York 1970-2001: Art & Experience, will be published next year by Yale University Press.