A few years ago, I was planning a trip to meet my mom for a long weekend and wanted to find a place about halfway between her home in Salem, Oregon, where I grew up, and my (then) house in Berkeley. I looked at a map and was reminded of Port Orford, a tiny town of 1,000 that my beloved grandma enjoyed visiting throughout her life. Almost no one knows where Port Orford is—not even most other Oregonians. It is so very small and remote.

During my first trip to Port Orford a kind of magic descended, and I became enamored with the town. I’ve often felt that towns are like people: either they are easy to fall in love with, or not so much. I was very smitten with Port Orford. While I had loved and thoroughly partook in all that the San Francisco Bay Area had to offer for the previous 22 years, I was very ready for a change.

In Port Orford on that first visit, people waved at me from their beat up trucks while someone played the banjo on a crooked porch. At the grocery store, on my second day there, the cashier got on the loudspeaker and asked everyone to come to the front of the store. As I had been teaching high school English for the decade prior, I was anxiously anticipating trouble, but what type was unclear. Not a school shooter drill (which had been my first thought) but surely something else terrible. A tsunami? Nope. When the shoppers made it to the front of the store, the cashier let us know that little Kelsey was turning nine and we should all sing happy birthday. Where was I?

Since moving to Port Orford, it feels like I was adopted into a big, dysfunctional family—the long-lost cousin welcomed with open arms (for the most part). I love knowing so many people’s names, love knowing who their kids are, and love being yelled at from the side of the road to meet folks later for music or a drink. There is absolutely nothing that could make me live in any other city or town again; I am already far too attached to jumping in these particular rivers, visiting the two nesting hawks in the pasture north of town, and of my regular walks in the forest and along this rustic coastline. I also fell in love with someone, and opened a bookstore. It has been a dream.

Except for one thing: pronouns.

In urban areas, at least those along the West Coast, I have grown accustomed to people having an understanding of pronouns—of waitstaff at restaurants using gender-neutral greetings, of “What’s your preferred pronoun?” being a normal part of a conversation. I’ve always been androgynous, have always felt ‘in the middle.’ When I had top surgery, I explored taking testosterone, but decided it wasn’t for me. I loved my androgyny, loved having a masculine-of-center presentation and a soft voice, and loved having a flat chest and short hair. I also appreciated having been socialized as female: of being emotional and empathetic and attuned to others. And I loved, and still love, having that reflected in how I’m perceived by others.

It feels pretty terrible (even though, or maybe because, I know who I am so thoroughly) to be misgendered, which happens a lot in my town. A little liberal enclave in a region thick with conservatives, Port Orford is full of homesteaders, artists, musicians of all ages, young families and retirees. There are fishing people and service workers and librarians and tradespeople. Few people have managed to use the they/them pronouns that I prefer.

I anticipated having to explain pronouns—specifically the they/them pronouns I use—but I didn’t anticipate people saying to me, “Well, I just don’t get it.” Or “I’m too old for this.” Or “I don’t really want to try and honestly don’t think it’s worth the effort.” Not in so many words, but in their actions. Most people here refer to me with she/her pronouns and every time it happens, it is a punch to the gut that makes me feel isolated, unseen, frustrated, and disappointed. Some people try and still get it wrong, and that’s okay. I’m content enough if someone makes an effort to grapple with something new to them. I understand that it takes practice, some reframing, an openness, and personal effort. We have all been so thoroughly and narrowly trained.

I am still not sure how to understand it, but besides the rules of grammar and language, I think people are uncomfortable or resistant to the thing underneath, the reality of gender ambiguity. Humans are fond of categories, and we love the binary: white/black, male/female, young/old. When one’s identity is unclear, it often results in anxiety or resistance, sometimes outright aversion.

The people who have seemingly given up on trying (at least for now) to get my pronouns right are lovely people who I can tell like me; they come to my bookstore, offer smiles and hugs when we meet on the street. I am working to understand what it is that causes this rift, this buckling down into binary notions. Sometimes I fantasize about sitting down with each of the people who seem committed to ‘she-ing’ me, and ask them to take a step back and reflect: What is it that makes them think I’m female? Or why do they think they know anyone’s gender for that matter? I hope one day these kinds of assumptions are not made, and that we learn to refrain from sizing one another up in seconds. At the same time, I’d also like to live in a world where language matters—that we were all a little more thoughtful with it.

When I substitute teach at the local high school (where no one is allowed to use the word gay) there are always young people who come up and ask me what my pronouns are. As usual, it is the youth who give me the most hope, but I’m not yet willing to write off their elders.

As Milan Kundera wrote, “The greater the ambiguity, the greater the pleasure” and I have found this to be true. Existing in a liminal space of my own making has been the most freeing reality I could imagine as a human, and I wouldn’t give it up for anything. It is the gift of a lifetime.

Torrey House Press just published my debut novel, “A Wounded Deer Leaps Highest.” And just like Smokey, the child narrator, I will seek refuge in the trees and animals, in the rivers and under starry skies for the rest of my life, hoping the humans in my community are eventually able to set aside their belief in the binary, and see me as I am.

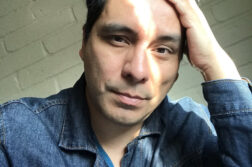

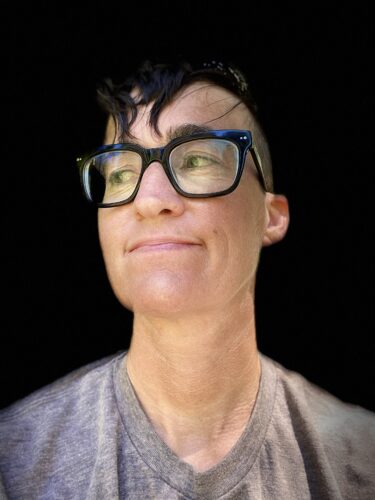

Charlie J. Stephens is a queer, non-binary, mixed-race writer from the Pacific Northwest. Resident of Port Orford on the southern Oregon coast, they are the owner of Sea Wolf Books & Community Writing Center. Charlie’s short fiction has appeared in Electric Literature, Best Small Fictions Anthology, New World Writing, Original Plumbing/Feminist Press, and elsewhere. Their debut novel, A Wounded Deer Leaps Highest, was published by Torrey House Press in April 2024. You can read more on their website and follow them on Instagram @