I chose Auden’s “Funeral Blues” for the program of my brother’s funeral. My own words had failed. I was grateful that another writer had crafted them, for the timelessness of their meaning, and for the relevance of poetry.

On June 11, 2002, my oldest brother died of a heart attack. Stephen was forty. Two days prior he had collapsed in my arms. I held him as long as I could.

We were eight years apart. Early in our childhood, we realized we were both different and alike, falling branches of the same family tree. Our family, conservative Republicans, were natives of Wilmington, Delaware. My mother, a member of the Colonial Dames, traced our lineage to the 1700s.

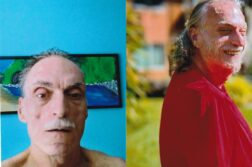

Stephen fit all of the stereotypes. He loved theater. He loved Cher. He was witty, charming, and had a distinct flair for the dramatic. He wrote his first play in high school. He had chestnut hair and eyes, like my mother’s side of the family. He was not an athlete and therefore ignored by most of the men.

In photographs, Stephen smiles tenderly at me through the bars of my crib. One of my earliest memories is of him helping me with my homework. I was six. Our parents were out. I was in bed, but realized I have forgotten to do my homework, a map of our neighborhood. I ran to find him, in tears, afraid of our parents’ return and my teacher’s disappointment. He sat me down at the kitchen table, poured me a glass of milk, and told me not to worry. He helped me trace an outline of our house, a colonial with white brick and black shutters. We switched off the lights as the key turned in the lock.

Another early memory: my father taunting Stephen at the dinner table, a routine teasing, and me laughing at my brother, at the same time knowing I was wrong, but knowing I was trying to survive. My face burned. It was at that moment I saw my brother, and myself, clearly.

The weeks and months before his death, I had urged him to go to the doctor. He had complained of stomach pain and indigestion. He was a smoker, and a closeted gay man with depression, anxiety and a family history of heart disease. All of his life, society told him he was not the right kind of boy, and, later, not the right kind of man.

Despite this, we drank and smoked and laughed. Every Sunday we met for dinner at our East Village bar. I wish I had known the signs. I wish we had gone for walks. I wish we had both felt worthy of health and love and happiness, or of longevity and time. I wish we had both been “out,” our authentic selves, without fear of violence, judgment, reproach.

Stephen and I shared a secret language—of siblings and queer survival. We shared glances across a holiday table. We felt the visceral, redemptive feeling of being seen, heard, and recognized. Loved, wholly.

What happens to sibling language when a brother dies? What happens to memory, to meaning? What happens to identity and family structure? What happens to all the unspoken truths?

Mary Warren Foulk is a educator, writer, poet, and activist whose work has been published in VoiceCatcher, Cathexis Northwest Press, Yes Poetry, Arlington Literary Journal, Los Angeles Poet Society, Pine Hills Review, Palette Poetry, Visitant, Silkworm, and Steam Ticket among other publications. She is the author of If I Could Write You a Happier Ending. A graduate of the MFA Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and lives in western Massachusetts with her wife and two children.

Mary Warren Foulk is a educator, writer, poet, and activist whose work has been published in VoiceCatcher, Cathexis Northwest Press, Yes Poetry, Arlington Literary Journal, Los Angeles Poet Society, Pine Hills Review, Palette Poetry, Visitant, Silkworm, and Steam Ticket among other publications. She is the author of If I Could Write You a Happier Ending. A graduate of the MFA Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and lives in western Massachusetts with her wife and two children.

Discussion6 Comments

Mary

What a nice story I always loved Stephen & so did the DTC !!

Am proud of both of you 🎶💕

Avec appréciation

MaryPage

Mary Warren,

I loved reading this and have many fond memories of Stephen. He was a cool guy, always preppy, handsome and sweet. He loved family and always spent time visiting cousins, aunts and uncles when in Orange. I thought of him as an individual with clear plans for a successful future. He left this world too early, but I am sure God had plans for him.

Your parents and grandparents would be so proud of you!

Love,

Bev

Mary-

What a powerful story of loss and live and unspoken secrets! How sad that your beloved brother died so young! Sending love and feeling gratitude for you and your writing…

Worthy of Health, Love , Happiness Longevity and Time !!! Life affirming words . Thanks Mary for sharing your heart and memories about your brother Stephen .

Remarkably poignant and elegiac…reminded me of the deeply profound feelings I experienced when I lost my own brother far too soon: You elegantly captured our shared humanity,

He was very lucky to have a sister who spoke his language. And you lucky that he saw you through the bars of your crib.

I lost a cousin who was like my brother to hiv/aids and no one in the family knows the lost language. It can be a sad place to reside, but remembering the ghosts of those words and glances still brings great joy. Yes, ghost words thrive