This is the first half of a series of reviews, featuring short films that highlight the nonbinary experience. You can expect one more review and an overarching reflection next week!

Stories about non-binary humans are rare. I say non-binary humans because there are plenty of genderfluid characters in books, TV, and film who are robots or intergalactic aliens. It would be nice to every so often experience stories and characters that reflect those of us here on earth that struggle with (and celebrate!) their binary gender identity.

But I’m an impatient, compulsive them, so I recently Googled something along the lines of “non-binary film” and “non-binary art” in the hopes of finding something, anything, that was representative of the human genderqueer experience. I had no expectations and was more than prepared to be disappointed. The end result was a euphoric rainy mid-afternoon watching three flawed but wonderful short films, all on YouTube and centered around the non-binary experience and featuring non-binary main characters.

These films were Still Me, directed by Jay Beckerleg and Sam Jelley; Labels, directed by Courtney McCollough; and They/Them, directed by Beau Beaufill; and each of these films present unique visions and explorations of the non-binary experience. At the same time, they are ultimately united in that they deal with the struggle of taking ownership of one’s personal identity and body in an oppressively cisgendered world.

Still Me and They/Them are traditional coming-of-age narratives, while Labels is on the more experimental and surreal side. The two more traditional short films present a kind of bittersweet — at times triumphalist — narrative that brings to mind films like Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, and Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight. Labels is more abstract and captures a kind of undefinable trauma that comes with gender dysphoria and queerness in general.

***

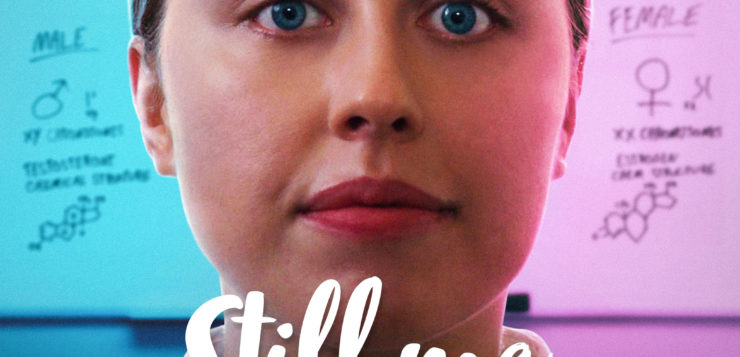

Still Me

Still Me

Jay Beckerleg and Sam Jelley, dirs.

Still Me opens dramatically with main character Bailey introducing themself outside two gendered bathrooms amid a panic attack.

“I know I’ve had a different name as long as you’ve all known me,” says Bailey, shaking and in tears. “But, please… just call me Bailey.”

We are to surmise that this is the first day Bailey is presenting themself as non-binary at school and soon after the opening scene, when in class their teacher refers to them by their deadname, Bailey forces a smile and gently says, “I’m sorry Miss, it’s Bailey now.”The teacher is dismissive and the other kids murmur among themselves; Bailey is left completely isolated with nothing else to do but remove their beanie and sigh.

As a cruel reward for their bravery, vulnerability and attempt to take control of their own gender identity, Bailey is soon bullied by their peers, abandoned by their friends, and ignored by teachers. Things reach a climax when Bailey suffers a severe panic attack during a lesson on gender. When the teacher asks the boys and girls to be separated, Bailey begins to heave and, ultimately, rushes out of the room. A student named Zach, who turns out to be queer, discovers Bailey crying and heaving by themself in an empty classroom. Zach, with a mix of cool, tough love and tender compassion, helps Bailey through their panic attack.

“I’m Emily,” says Bailey.

“Are you though?” replies Zach.

Bailey shakes their head. “No.”

Zach becomes a mentor for Bailey and opens Bailey’s eyes to possibilities of euphoric queer existance, the kind of which they had never conceived.

This was easily the best acted short-film of the three I am writing about in this piece. Parkin’s performance as Bailey, in particular, is moving and powerful. They portray a blend of bravery, sorrow, and pride familiar to any out non-binary person dealing with rejection and misunderstanding. Bailey holds a muted, prohibited rage that reveals itself in panic attacks and blood swallowing patience such as when their teacher refuses to not call them by their deadname.

More than just a queer high school melodrama, Still Me actually struck me as something almost resembling a prison narrative. Bailey is isolated and powerless within the crushing physical and psychological structure of their school and there does not seem to be an escape. The character of Zach actually reminded me quite a bit of the inmate Baines (Albert Hall) from Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X during the title character’s years in prison. Baines, a composite character based on a small handful of real-life figures, in particular a fellow called Bimbi, meets Malcolm (Denzel Washington) in prison and urges the troubled, alienated young man to embrace self-love through racial pride and to reject the narrow mindframe inflicted by the white oppressor. Baines talks, reads, and prays with Malcolm, and teaches him what it is to be proud and fearless about his black skin, heritage, and culture.

Like Baines — at least before he is released from prison — Still Me’s Zach maintains a confident wisdom that one can surmise has been gained through some degree of strife and scarring. It turns out that Still Me is a sequel to 2019’s Masked, which is about Zach’s trans journey. In Still Me, we see a respectful — though a bit more gentle than Baines’s — sternness that comes from a place of love for their mentee, and a deep appreciation for the power of identity and community.

The next time Bailey reveals their name, pronouns, and non-binaryness, they do it with newfound confidence and pride. But then one realizes that Bailey has had these traits all along, having, after all, bravely come out to the audience in the opening scene. Sometimes it just takes a special mentor and a loving community to appreciate these traits in one’s self.

Let it be understood, in the end, that one should not watch Still Me, nor They/Them, expecting highly innovative, genre-bending cinema (though gender bending is another matter!). Still Me’s narrative is predictable and there is a slight tendency toward teenage melodrama, which is understandable given the target audience. Nonetheless I found myself quite emotionally taken by the film and I think a lot of that has to do with the acting of the non-binary actors Parkin and Adelaide as the brave and powerful Bailey and Zach.

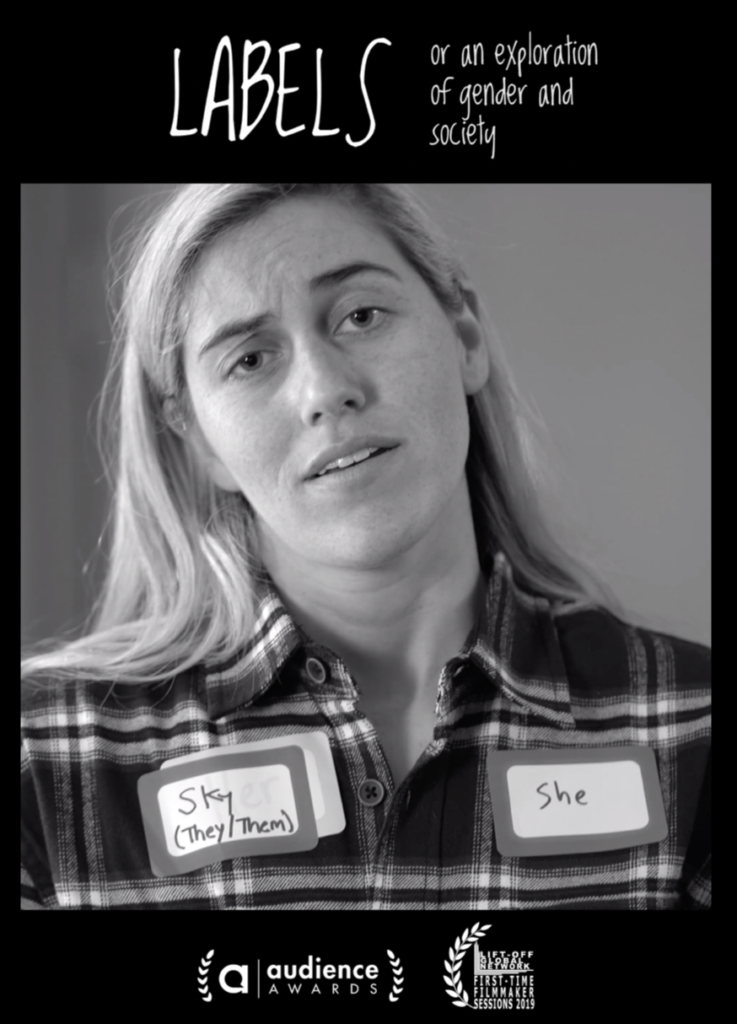

Labels, is silent and black and white but nonetheless takes place in the most modern of settings – a so-called “young professional meetup” well stocked with cheap booze and snacks in an urban apartment. Its main character is the non-binary, blonde-haired Sky; who, dressed in striped flannel and jeans, makes their way around the dream-like “young professional Meetup” greeting friends and acquaintances. They attempt to don a little name tag which indicates their name and pronouns but this proves difficult. Just as they’re about to paste the thing below their lapel, they discover that another name tag, which simply reads “Her”, has already been placed there. Sky’s initial solution is to sort of shake the whole thing off and just place their they/them nametag on top of the mysterious cisgendered one.

Labels, is silent and black and white but nonetheless takes place in the most modern of settings – a so-called “young professional meetup” well stocked with cheap booze and snacks in an urban apartment. Its main character is the non-binary, blonde-haired Sky; who, dressed in striped flannel and jeans, makes their way around the dream-like “young professional Meetup” greeting friends and acquaintances. They attempt to don a little name tag which indicates their name and pronouns but this proves difficult. Just as they’re about to paste the thing below their lapel, they discover that another name tag, which simply reads “Her”, has already been placed there. Sky’s initial solution is to sort of shake the whole thing off and just place their they/them nametag on top of the mysterious cisgendered one.

As Sky moves around the apartment and mingles, new cisgendered name tags and labels appear on their clothes and body. This leads to a game of whack-a-mole where Sky tries, in vain, to remove and erase these labels that do not suit them. It gets so intense and out of control that Sky finds that they must rush into the bathroom so as to scrub off a phantom tattoo on their forearm which reads “WOMAN”. A young woman wearing a “girl power” necklace walks in and interrupts, and commences to hug Sky and put an identical necklace appears on their neck. Sky desperately tries to tear the thing off but cannot. Rather than help them dismantle the gift, the girl attempts to reassure Sky by stroking their long hair.

It only gets more nightmarish and uncanny from there. After the bathroom incident, Sky has finally, it seems, eliminated all the cisgendered labeling and has returned the they/them tag to its rightful place below their lapel. But one of Sky’s friends introduces them to a new acquaintance, and the latter appears to express confusion over the they/them nametag. Against their will, the friend attempts to negotiate, and a new “she/her” name tag is placed on Sky’s lapel against their will. The new acquaintance is assuaged, but Sky is by now quite disillusioned and melancholy.

Label’s ending is ambiguous. After the episode with the friend and acquaintance, Sky isolates themself in an empty bedroom and crashes on an unmade bed. After discovering it and crumpling up yet another cis-gendered label, they find one on the ground which reads, simply, “human.” Sky’s reaction to this is as ambiguous – their face shows a mix of relief and ambivalence.

Labels manages to leave the viewer with a lot to think about in just over five minutes. Its two main themes are complex and interrelated: The first is a theme shared with the other short films in these reviews – that of control of personal/gender identity and the erasure that results from even well-intentioned ignorance. In the aforementioned scene when a “she/her” nametag is placed on Sky’s lapel against their will to placate an uncomfortable peer, we see the extent to which one’s own feelings are devalued and erased so as to reassure the fragile, cis-gendered sensitivity of others.

The second theme is an inverted flip side of the first. Throughout Labels, Sky confronts the complicated gendered and cisgendered cultural realties that being non-binary can create confusing distance from. In other words, one can sense in Sky a kind of internal tug-of-war that can only come from the tension of suffering misogynist oppression and not being able to escape it while being perceived as cis-feminine. The key scene as it relates to this theme is the one in the bathroom, in which the young woman gives Sky the “girlpower” necklace. Sky doesn’t quite know what to do with it; ultimately opting, in vain, to rip it off their own neck.

Labels is on its surface very obviously about external, interpersonal challenges presented by gender queerness and internalized dysphoria. But dig a little deeper and you will find that there is also something being said here about about this same internal dysphoria manifesting itself interpersonally and culturally. It is a dramatization of a painful vicious cycle. That Sky’s only refuge seems to be to isolate themself and lock themself into an empty bedroom is indicative of their internal exasperation and external erasure. Those two things feed each other and dance in lockstep.

Labels is ultimately a wonderful — and quite melancholic — if unpolished, exploration of queer and non-binary erasure, pride, and dysphoria that requires multiple close watches to appreciate.

Toby Jaffe is a writer from New Jersey whose work has been published in The New Republic, American Prospect, Paste Magazine, and The New York Review of Architecture. Follow them on twitter at @JaffeToby.