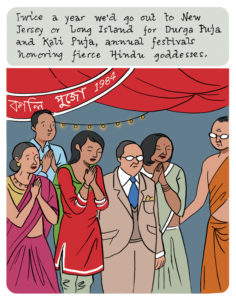

LIKE A LOT of Bengali families, we had images of Hindu goddesses adorning the walls of our home growing up in New York City. Hindus adopt their favorite deities from within the Hindu pantheon, according to where they’re from in India or what their profession is. Merchants, for example, favor Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, or Laxmi, the goddess of wealth. Kali, the destroyer—blue black-skinned, naked save for a skirt made of human arms, and a necklace of human heads—is the fearsome avatar of the mother goddess Durga, who is sari-clad, brandishing weapons, astride a tiger. Both are beloved by Bengalis, including my own family. It was Saraswati who my mother honored with a choreographed puja, a Hindu ritual of worship, before my exams at school. The goddess of knowledge, arts, and music was depicted playing a veena (an Indian stringed instrument) and riding a swan.

Growing up, I took it for granted that we worshipped goddesses. I didn’t realize until around middle school that this was a bit of an anomaly. I may have been the only kid in my grade whose parents brought them up to kneel before images of women, to salute distinctly feminine divinities. It all sounds like a formula for a tolerant attitude toward women loving women, right? And yet, the acknowledgement of feminine love did not exempt my parents from a certain strain of Indian conservatism that frowned upon anything to do with LGBT matters.

Once, when I came home at 5 am after a night out in the East Village, dolled up in Goth gear, my hair teased up, my eyes lined with kohl, my mother berated me: “I almost called the police! And look at you! You look like a girl!” My folks must have been scared that the proximity of Goth to femme meant that I was a gay boy. I told them I wasn’t, which was my truth.

But eighteen-year-old me hadn’t the foggiest notion of what harbor I would one day call home. Indeed I was still at sea through my thirties—trying to make a go of establishing myself in architecture, flailing about with looks, clothes, and identities—when both my parents died within three years of each other.

Several years later, I abandoned my so-called career to dive into making art and comics. My hair grew past my shoulders, down my back. I traded in my architecture-office-friendly J. Crew sweaters for black tunics, skintight black jeans, black leather boots. Eighteen-year-old me had come home to roost in my 45-year-old body.

As I sought success in my new artistic pursuits, I once again asked for guidance and fortune from Saraswati and for strength from Kali and Durga. As gray hairs started to sprout amongst my witchy ebony locks, I started to resemble my mother. As I reflected on myself with the advantage of maturity, I realized: I am a daughter of these devis, these goddesses. The divine feminine essence that had been such a lodestone of my childhood was shaping me psychically and fleshing out my essence—at the heart of this transformation was an embrace of my gender, my trans-ness.

There are kernels of trans-positivity scattered throughout the stories and histories of Hinduism. In the Ramayana, for example, there is an account of Lord Rama, the seventh avatar of Vishnu, who, on returning home from a fourteen-year exile in the forest, and touched by the devotion of a group of hijras (third-gender or transgender women), bestowed on them the power to confer divine blessings themselves. Lord Siva and his companion Parvati are sometimes jointly depicted as the Ardhanarishvara, or a composite figure who is half male and half female, split evenly down the middle, an acknowledgement of the Shakti, the divine feminine energy that pervades all beings. Finally, there are several renowned monuments of Hinduism that bear witness to its openness towards sexuality in general: you only have to read the Kama Sutra or visit the erotic carvings of the temples of Khajurao to see this for yourself.

It is within this open space that I make room for these beliefs: I believe that the mother goddesses planted in me the seeds of devotion and that they made me this way very specifically. I believe that these avatars of Shakti wield and distribute femme vitalities and that when they decided to make me trans, they did so as a gift to me. I believe that if and when we exit this dark age, this time of chaos and upheaval, a distinctly femme constellation of energies will guide us.

Bishakh Som’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, We’re Still Here (The first all-trans comics anthology), Beyond, vol. 2, The Strumpet, The Boston Review, Black Warrior Review, VICE, The Brooklyn Rail, Buzzfeed, Ink Brick, The Huffington Post, The Graphic Canon vol. 3 and Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream. She received the Xeric grant in 2003 for her comics collection Angel. Her graphic novel Apsara Engine is out now from The Feminist Press and her graphic memoir Spellbound has been published by Street Noise Books. www.bishakh.com