I FIRST READ Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past—which was the English title given to the monumental novel by its first English translator, C. K. Scott Moncrieff*—when I was around thirty. I’d heard that one should never attempt to read Proust before that age, because much of it would be lost on you. And so, every day for nearly a year and a half as my bus made slow progress going to and from work in Chicago in 1991, I patiently made my way through volume after volume. I remember being both dazzled and frustrated by the work, and there were indeed days when the leisurely pace of Proust’s prose, which, with its constant and insistent insertion of parentheticals, actually forces one to slow down, was simply beyond the level of my attention.

Now, however, in the middle of a pandemic lockdown in which there was nothing but silence, I thought about revisiting those long, leisurely sentences and returning to that marvelously recreated world of late 19th-century France. Indeed, coming to the work a second time, and now at age sixty, one of the things I most appreciated was the calmness and intricacy of the prose, and the way it forced one to pay attention. I was also constantly amazed by how seamless and sustained the writing was, so that, even though most days I was only able to manage twenty pages or so, after putting it aside for a day or two, I could easily pick up where I’d left off and instantly re-engage with the workings of Proust’s mind. I found a calming, almost healing quality in that.

There were, however, differences in my reactions this time around. For instance, at thirty, having just come out of the closet myself, I found the portrait of Charlus, a gay man, to be appalling and cringe-worthy, even reprehensible. Similarly, the depiction of Odette and Albertine’s lesbianism was equally lamentable. Though I still found much to object to upon rereading, what struck me was how brave Proust actually was in presenting such a complex, eminently recognizable portrait of a closeted gay man. The fact that no one had really ever addressed these issues so frankly before allowed me to forgive some of the more unforgivable statements Proust made as he wrote about that world while hiding the fact that he himself was gay.

With the passage of time, I also felt better able to understand the poignancy and brilliance of Proust’s depiction of the pains of the heart. There is surely no more affecting portrayal of tortured love in all of literature than Proust’s portrait of Swann in love with the unworthy Odette. That said, and despite the brilliance of Proust’s perceptions about love as played out in the narrator’s love affairs with Gilberte and Albertine, what struck me was how Proust’s concept of love is so often associated with jealousy and possessiveness. So, even as I admired the portraits of tortured people pursuing unattainable objects, I also found myself on a different plain of understanding about the foolishness of such pursuits.

Remembrance of Things Past opens with the narrator recollecting an evening in childhood when he waited long and patiently for a kiss from his mother in order to fall asleep. For page after page, Proust elaborates his thoughts and emotions while waiting for this sign, so the kiss becomes a kind of metaphor for the way many people suffer as they await love’s arrival. This waiting also comes to symbolize that love can never quite be attained, and that the “glory” of love depends upon how much one suffers in its name. Indeed, knowing that Proust sacrificed his own life by locking himself up in a cork-lined room year after year to commit his novel to paper, one can’t help wondering if he was really trying to recover the last time he truly felt something. Ironically, by locking himself away in this manner, he virtually guaranteed that he would never find happiness.

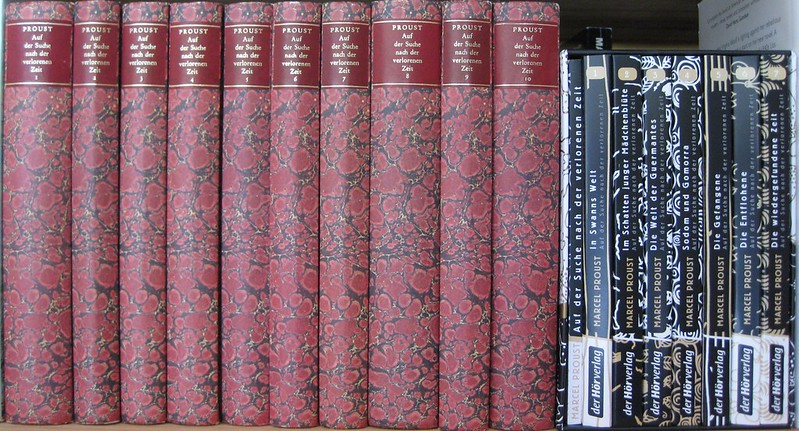

And yet, Proust’s novel is a wholly satisfying work—surely one of the greatest novels ever written—a work whose subject is consciousness itself. Every educated reader should read at least the Overture; and if one is not ready to commit to all seven volumes, Swann’s Way (volume one) contains nearly all the themes of the other six, and is perhaps the most beautiful and self-contained. I can think of no other way to summarize the beauty and poignancy of this beautiful, daunting, aggravating, and astounding work than to end with the words Proust uses as he recalls that night so long ago, when he awaited his mother’s kiss:

Many years have passed since that night. The wall of the staircase, up which I had watched the light of his candle gradually climb, was long ago demolished. And in myself, too, many things have perished which, I imagined, would last forever, and new structures have arisen, giving birth to new sorrows and new joys which in those days I could not have foreseen, just as now the old are difficult of comprehension.

Dale Boyer is the author of The Dandelion Cloud, Thornton Stories, and Justin & the Magic Stone.