In July 2000, my partner Rob and I spent several weeks in Italy, beginning in Rome. We came to the Eternal City for World Pride Roma, a week of gay cultural and political activities culminating in a march. The event attracted several hundred thousand gay men, lesbians, trans people, and heterosexual allies, from Italy and abroad. But World Pride, an international celebration held in a different capital city each year, almost didn’t make it to Rome. The Vatican and its conservative political allies waged a vituperative, unabashedly bigoted campaign to prevent it from being held in Rome in 2000, the year of the Giubileo, the Catholic Church’s millennial Holy Year celebration.

The opposition to World Pride Roma backfired; it ended up generating an outpouring of support from Italians who believed that the attempts to ban it constituted an assault on the Constitution and lo stato laico, the secular state. Support came from a wide range of public figures, from the president of Rome’s Jewish community to artists such as filmmaker Nanni Moretti and the playwright Dario Fo, as well as from liberal and leftist political parties, civil society organizations, trade unions, and even grassroots Catholic associations that condemned the Vatican’s stance. The leftist newspaper Il Manifesto published a statement of solidarity titled, “Siamo tutti gay” (“We are all gay”).

World Pride Roma 2000 was a great success. Its significance, however, was greater than the size of the crowds or even the defeat of its formidable foes. What the event signaled was the refusal of the gay population—or at least its activists—to accept the unfavorable terms of the social contract offered by Italian society. Male and female homosexual behavior has been legal in Italy since 1890. Italy does not have sodomy laws, and the age of consent is fourteen, for both hetero- and homosexuals.

The absence of legal prohibitions, however, didn’t mean there was no stigma or discrimination. Catholicism may no longer be Italy’s official state religion, but its influence remains pervasive. Social attitudes towards homosexuality are strongly influenced by the Church’s stance that it is both sinful and unnatural, and that gay people should be tolerated only as long as they suffer their condition in silence and don’t demand civil rights or social acceptance.

In 2000, there were no anti-discrimination laws in Italy (employment discrimination was banned in 2003), and it wasn’t until 2016 that same-sex civil unions became legal. At the dawn of the 21st century, Italy was very much the land of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” Don’t tell your friends, your coworkers, your schoolmates, and above all your family. (It would kill your mother! Given how often I’ve heard that one, Italian mothers must be a very fragile species indeed.)

World Pride challenged this societal omertà. “In Italy, invisibility has been the price for tolerance,” observed Sergio Lo Giudice, at that time the president of Aricgay, the national gay rights association. “But gays don’t want to be invisible anymore.”

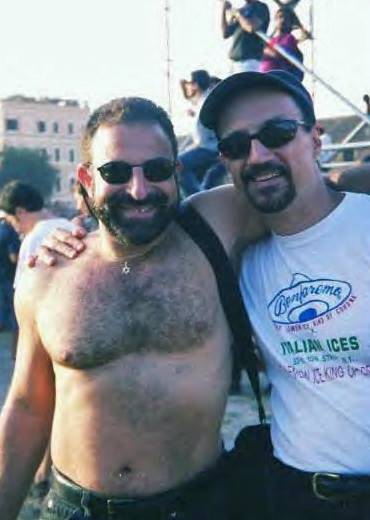

While in Rome, we met up with Salvo, a friend who had come from Sicily to march in World Pride. As we stepped off the sidewalk to join the marchers, Salvo, with tears in his eyes, said, “You have no idea how much this means to us.”

Two weeks later, Rob and I went to Sicily to visit him and two other friends, Gianni and Salvone. The couple had planned a trip for the four of us in Selinunte, an ancient, picturesque town of Greek and Phoenician origins on the island’s west coast. After the long drive from Catania, the main city of eastern Sicily, we arrived at our hotel. As we were checking in, there was a problem. Gianni had reserved two rooms with double beds, for Rob and me, and for him and Salvone. But the clerk decided that four men could not have accommodations with the letto matrimoniale, literally the “marriage bed.” He insisted we take rooms with single beds. Gianni refused to accept this. The conversation escalated into an argument, with rising decibels and growing frustration on both sides. Gianni, a university professor from an upper-middle-class family, code-switched from his usual polished Italian to the more emphatic Sicilian dialect. The clerk’s boss emerged from his office, quickly assessed the situation, and then told his underling, “Let them have what they want.”

Word of Gianni’s intervention, and our presence, spread at the hotel. Our clearly gay waiter in the hotel’s restaurant was notably friendly and solicitous. A British family at a nearby table, enjoying their meal, was oblivious to the fact that their teenage son was smiling and winking at us.

Back in New York City, after an eventful Italian sojourn that began in Rome and ended in Sicily, we received an e-mail from Gianni. He said that he and Salvone enjoyed the time the four of us spent together and that they looked forward to seeing us again. Then he put the confrontation with the hotel desk clerk at Selinunte in a different and surprising light. It turned out that the success of World Pride Roma, and the example of Rob’s and my openness about our sexuality, had encouraged Gianni to challenge the disapproving clerk.

“Thank you,” he said, “for bringing some of the spirit of World Pride to Sicily.”

George de Stefano is a writer and editor living in Queens, New York with his spouse, Rob Eisdorfer.