I HADN’T PLANNED on transitioning at Harvard. No one would choose to invite puberty to graduate school, but I probably wouldn’t have finished my degree if I hadn’t started injecting testosterone into my thigh in my second semester. Surprisingly, in 2011, an esteemed liberal arts program turned out to be a perfectly comfortable place to renovate my identity. They had great health insurance; and most academics love a fresh opportunity to be culturally sensitive.

I didn’t tell the Divinity School they were my exit strategy from the life I was trying to incinerate when I applied. I told them about the queer bar I had opened to provide a sanctuary for my people. I then related my eight semesters of ancient Greek and fascination with Late Second Temple Judaism to my dyke bar prophecy, and they were all in. Harvard Divinity School cultivates diversity, and they had never had one of me before.

By the time I landed at Harvard, I was forty and emotionally and physically exhausted from a lifetime of manual labor, interpersonal conflict, debauchery, and hope. Hope is the most debilitating of these afflictions because it is the relentless belief the world might favor you more warmly if you could only confound and exceed its expectations. This is a fruitless exercise for a woman who looks like they don’t want to have sex with men or make babies.

I had lived my whole life as a masculine woman, a butch dyke. Even as a child, my uncommon presentation was unmistakable. In adolescence my sexuality was obvious. In every mundane, daily interaction from my earliest memory, I was a naturally occurring contradiction. I was a circumstance that demanded a response, whether it be curiosity, denial, discomfort, anger, ridicule, or fetishization. Circumstances don’t develop a healthy self-perception or even a sense of human entitlement. From my experience, they simply seek to limit risk.

As soon as I could, I moved to San Francisco, where I’d heard there were other people that looked like me. I also found people who thought the way I looked was cute. Clots of rebel affinities used to form freely in cities. These magic bubbles of the marginalized might have broken your heart, but at least there was enough safety for a young ego to start to form. Heteronormative people rarely entered those spaces out of fear. That means the standards for cultural acceptance were set by one’s peers rather than dominant society, and the outside world was obscured. I never had to wear a dress again, but I worked overtime at being cool.

When I wanted a less strenuous version of this kind of refuge, I moved to Minneapolis. This is where I opened a queer bar in an effort to preserve the wild enchantment of queer spaces against the encroaching environmental forces of normative assimilation in the broader LGBT agenda. Dyke bars across America were dying at the time. Mine died too. I didn’t know what else I could do to provide a natural habitat for people like me, so I decided to try something completely different, go someplace I’d never been, which is how I ended up in the Ivy League.

I chose Harvard as a last-ditch attempt to exceed expectations, mine and probably those of my parents. We all needed a win. I wasn’t thinking ahead to what the experience might actually involve. I just wanted to see my parents at a graduation party, unable to formulate any clever critiques of my life choices because every Harvard degree comes with at least one afternoon of uninterrupted parental restraint.

Preoccupied by this fantasy, I didn’t plan ahead. I didn’t think about what I was going to wear. I didn’t know what classes I wanted to take. I did not anticipate the nature of my future classmates. I assumed I could charm anyone.

I know not everyone who attends Harvard is rich and snobby, but there is a pervasive comfort with comfort. I’d had plenty of practice with people with money, but Marx would have called where I came from the bourgeoisie. My home for the previous twenty years had been the dissident proletariat. As a butch dyke, if you wanted a cute girl to think you were hot, you had to be smart, edgy, and working-class. I spent twenty years driving trucks and forklifts, pretending to understand Kant. I’d owned a bar and drank like a pirate. This blue-collar mystique had been part of why Harvard let me in, but it provided no practical skillset for success there.

I was away from the safety of the fringe for the first time in two decades. I was dressed like a steampunk coal miner when I arrived on campus the first day. I was surrounded by attractive, confident, intelligent people. My costume was my armor. I was minimizing risk again, trying to appear intimidating like a spiked mollusk. And then, everybody was nice. It was damn uncomfortable. I couldn’t discern the ingredients of the niceness, but I couldn’t help the sensation of feeling like a zoo exhibit. I will admit to half of this impression stemming from insecure emotional projection, but how the hell is an aging pirate to behave when everyone thinks of them as an interesting subculture?

I unraveled. There was no one to fight and no one to protect. This experience suddenly became my responsibility to either master or waste. I wasn’t just back in the mainstream world; I was in a rarified version of it. Everyone around me assumed I was a real person with interesting things to say, or they wouldn’t have let me in. I didn’t know how to be anything but a hustle, and I was exposed and depleted. I gave up on changing the world, so I changed myself.

Testosterone turned out to be better armor. My masculinity is never questioned anymore. I made it through my master’s program and impressed my parents and myself. I haven’t made much of my fancy degree. I went home and became a bartender who writes things. The normal world is still uncomfortable for me, and I never did get new clothes, but I did find a chance at peace when I got that diploma. It gave me a trump card to deflect any future attack to my self-worth, either from the normative world or my own insecurity.

My transition story is uncommon, but that’s why it offers room for a new generation to find value in their own underappreciated triumphs and missteps. Some of us never do it the way everyone else does.

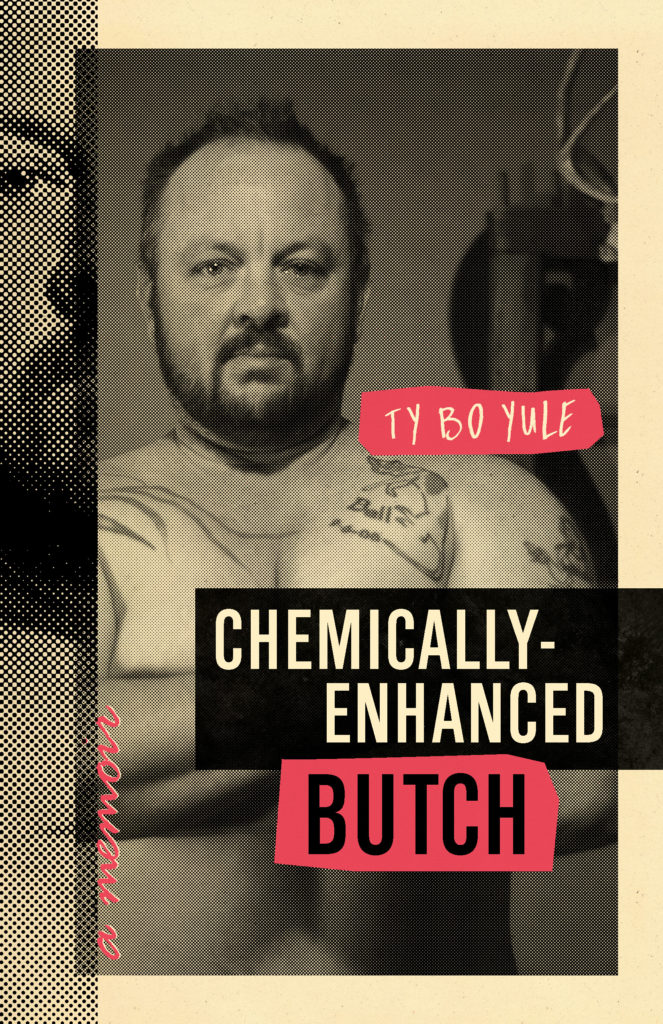

Ty Bo Yule is a Gen X trans masculine butch storyteller living and writing in Minneapolis. A newly elder queer reflecting on his vibrant and full queer life, he is eager to hear new stories. His memoir, Chemically Enhanced Butch, can be found at chemicallyenhancedbutch.com. His more recent thoughts and critiques of the intergenerational evolution of queerness can be found @tybobutch.medium.com.

Ty Bo Yule is a Gen X trans masculine butch storyteller living and writing in Minneapolis. A newly elder queer reflecting on his vibrant and full queer life, he is eager to hear new stories. His memoir, Chemically Enhanced Butch, can be found at chemicallyenhancedbutch.com. His more recent thoughts and critiques of the intergenerational evolution of queerness can be found @tybobutch.medium.com.