The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930

CHICAGO’S WRIGHTWOOD 659, a private institution focused on socially engaged art, is currently showing a landmark exhibition: The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869–1930. A team of international scholars, led by art historian Jonathan D. Katz has assembled a groundbreaking show that comprises over 100 paintings, prints, photographs, and film clips that reveal how, as Dr. Katz notes, “while language narrowed into a simplistic binary of homosexual / heterosexual, art gave form to a nuanced range of sexualities and genders that can best be described as queer.”

This trailblazing exhibition offers a tantalizing survey of the artists whose self-consciously queer art first fell under the category of “homosexual,” a term that was coined in Europe in 1869, catapulting same-sex desire into a new category of personal identity.

One of the show’s most exciting aspects is that it challenges conventional art history by lifting the cover from works that have not been widely understood as homoerotic. In doing so, it reveals how art became one of the primary vehicles through which “the love that dared not speak its name” was able to manifest itself. The exhibition also introduces some artists who are little known in the U.S. but revered in their own countries, including Gerda Wegener (Denmark), Eugène Jansson (Sweden), and Frances Hodgkins (New Zealand).

The First Homosexuals is divided into nine sections that offer a clear-eyed understanding of how the “first homosexuals” saw themselves and how dominant culture understood them.

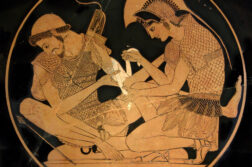

The first section, titled “Before Homosexuality,” features 19th-century works that demonstrate that same-sex eroticism was far from a new art subject before the debut of the word “homosexual.” In Europe, the representation of classical, mythological, and religious themes such as Saint Sebastian provided artists with ample opportunities to showcase homoerotic images and a remarkable array of sexual possibilities.

The second section, “Couples,” shines light on how many artists were romantically involved with other artists and often created works that depicted their partners. Louise Abbéma’s portrait of Sarah Bernhardt and herself by a lake was a tribute to their union. A standard exhibition would have focused on Bernhardt as a celebrity, ignoring their relationship, but this one identifies this as a portrait of domestic intimacy, showing how art can have alternate meanings, depending on the viewer.

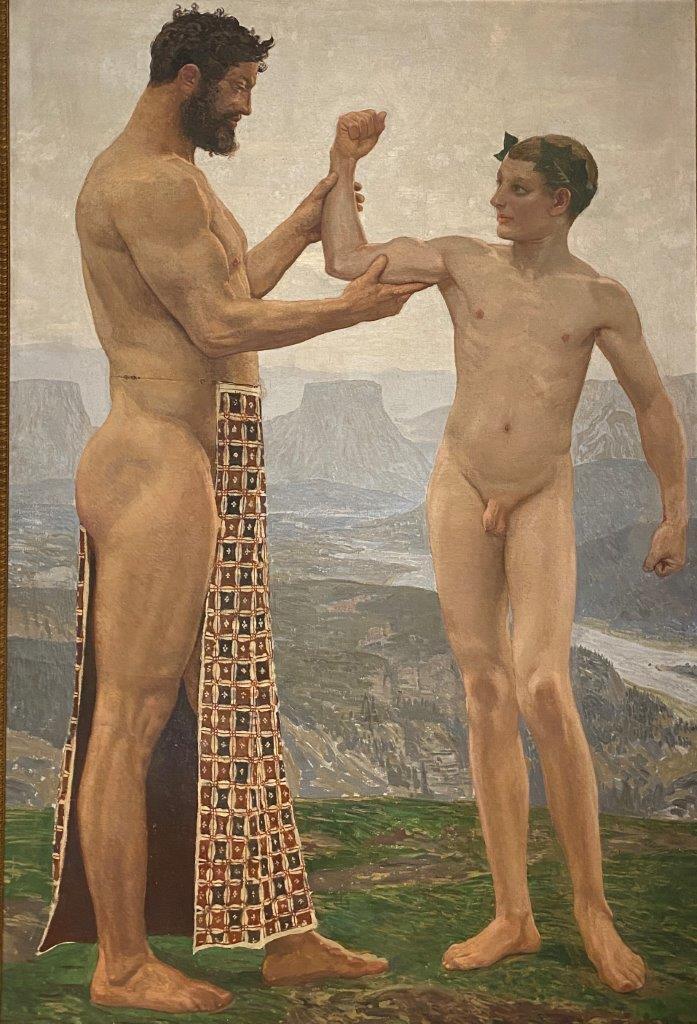

The third section, “Archetypes,” shows how the use of the term used was “Uranian,” suggesting a misalignment of soul and body, played out before the word “homosexuality” was coined. Here we discover how the ideal of male beauty evolved from the 19th-century ephebe, who combined both male and female traits, to a resolutely masculine ideal of perfection, epitomized by Thomas Eakins’ Salutat (1898). In this painting, a crowd not so much cheers a boxing victory as absorbs the exposed buttocks of a boxer glowing at the center of the canvas, the area historically reserved for eroticized female subjects. Sascha Schneider’s Growing Strength (1904), in which an ephebic youth is trained by a muscled older man, cements this new male ideal in a stunning image.

The fourth section, Pose, showcases the deployment of various codes of representation and the crafting of a persona to meet a condemning world. Roberto Montenegro’s iconic portrait of the antiques dealer Chucho Reyes (1926) features the limp wrist, the tilted chin, and the wry smile that signified a certain type of man. The artist included in the foreground a silver ball reflecting his own face, bringing himself into the picture, a proud declaration of his own connection to the main subject.

The fifth section, Between Genders, reminds us that the term “homosexual” obscures the distinction between sexual orientation and gender identity, which has come to the fore as part of the trans revolution unfolding around us. We can see here one of the first self-consciously trans images, Gerda Wegener’s 1929 portrait of her spouse as she understood herself: the woman Lili Elbe. Lili appears before having gender affirming surgery, but Gerda portrays her as her fully actualized in her womanhood, posing as an odalisque with a cigarette, an emblem of women’s liberation. Their tumultuous relationship was the basis for the film The Danish Girl.

The sixth section, Desire, shows significant distinctions between Western and Eastern imagery. While Western art rarely depicted sexual penetration in a fine arts context, such was not the case in Asia, where sex was understood not a something shameful but as a natural part of life. I was struck by a Japanese painted scroll from the mid-19th century that chronicles a young man’s coming of age as he moves seamlessly between women and men, dominance and submission.

“Public/Private” shows how homosexuality has been forced into the shadows, rendered invisible, stigmatized, and dangerous. Some artists challenged this dynamic, pushing homosexuality into the realm of public life. A beautiful example is Charles Demuth’s Eight O’clock (Early Morning) (1917), a provocative “morning after” scene with three young men. A melancholic figure, probably the artist himself, is addressed by a man in underwear as another nude man washes himself in the bathroom.

“Past and Future” shows how the exclusion of homosexual representation continues today. In the past the threat of erasure forced homosexual artists to use historical or mythical themes to legitimize their work. Baron von Gloeden’s photographs showcase naked youths with a Greek backdrop, evoking a Classical world in which same-sex desire was recognized as a part of life. In the premonitory painting Landscape with rainbows (1915) by queer Russian artist Konstantin Somov. a rainbow represents absolution and acceptance—63 years before Gilbert Baker introduced the first rainbow flag at a San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade.

In the final section, “Colonizing,” we learn how the arrival of “the homosexual” in Europe coincided with the advance of colonialism, a European expansionist ideology that used Darwinism to justify racism, military expansion, and even genocide. A pernicious side-effect was that Western ideologies on homosexuality were imposed on conquered lands, many of which respected same-sex relations or at least didn’t condemn them, and homophobic laws were written into their legal codes. In response to these attitudes, Sri Lankan artist David Paynter created in L’après midi (1935) a ravishing male version of Gauguin’s alluring female portraits.

After walking through the exhibition, we come to realize that sexuality is not an eternal category but a historical one that’s subject to dramatic changes in response to competing influences. In short, this is an extraordinary exhibition. If you aren’t able to see the show in Chicago, another opportunity will present itself in 2025, when 250 works will be assembled at the same museum for Part II, a major exhibition that will travel internationally, accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue.

Ignacio Darnaude is an art writer, lecturer and film producer. He is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight—Breaking the Queer Code in Art.