The 1990 Dutch documentary Na Het Feest, Zonder Afscheid Verdwenen tells the story of Willem Arondeus, artist, novelist, and Dutch Resistance worker in World War II. Arondeus lived his life as an openly gay man. He led an attack on a Nazi registry office to protect thousands of people hiding in the country. The attack on the registry succeeded, but the participants were caught. As he faced the Nazi firing squad, Arondeus’ final words were “homosexuals are not cowards.”

His message was one that I, a grieving gay boy, needed to hear. The previous summer, I’d fallen in love with a boy for the first time. Joseph, the older brother of a friend of mine, was a popular athlete who took my breath away and had me hoping, more than believing, that he might be interested in boys too. And interested he was.

After a couple of weeks of chatting him up at his summer job at a suburban movie theater, I made my move, my first move ever. Sleeping over at my friend’s house that night, I heard Joseph come in, late, after his shift at the multiplex. Summoning every bit of courage I possessed, I casually strolled into his room. He looked at me, and I looked right back, and we both knew, in that moment, that we had a secret, now a shared secret, one that scared us both to death. Scared and thrilled—that first night and all those perfect, secret nights that followed.

That was the summer of 1991, the dawn of that decade that saw so much anti-gay rhetoric and politics in the U.S., such as the “family values movements” and the Defense of Marriage Act.

Strangely—miraculously, even, as I look back on it—the politics of the era didn’t much enter into our world, at least at first. Even in 1991, even in Texas, neither of us thought what we were doing was wrong. Never once—as we met secretly, and kissed, and held each other, and talked, and, joyously figuring it all out, made love—did the question “Should we be doing this?” pass our lips.

Our secret made our romance all the more exhilarating. We’d find ourselves in a crowd or at the same party, and Joseph would look for me, discreetly run a finger along my inner thigh or mischievously whisper something into my ear, and my breath would catch, and I’d have to cover my awakened crotch. He would saunter away, giving me that grin of his, the one I still see in my sleep sometimes.

But secrets grow heavy with the keeping of them. We hardly knew of anyone who was out as gay in those days—hardly knew what being out was, there in suburban Texas. But for my next birthday, Joseph gave me his letterman jacket. When I opened up my present, I knew what he meant by it. He was giving me his blessing to come out as gay, and promising that he’d be there with me as we faced an exciting and scary future together.

Except: he didn’t stand with me for long. I came out, to my parents, just after that birthday. Joseph offered to be there with me as I did so, but I needed to do it alone, face my mom and dad without him, though I did wear that jacket when I told them.

He was proud of me. He told me so a million times, as he planned his own coming out. I could sense his fear, see his terror. He didn’t like me to see him cry, but he cried on my shoulder that week. I promised him he’d be okay, that we’d be okay, reminded him, by pinching on and kissing his biceps, how strong he was. And he laughed at my antics, as he always did, and we made love, a final time.

I got the phone call in the middle of the night from Joseph’s brother. My strong athlete had taken his life, injecting himself with a cocktail that included insulin and swallowing a handful of pills.

He kept his promise, I suppose, in the note he left behind. In it he came out, and brought me fully out with him, as people saw his suicide note, or simply gossiped about it. I didn’t even care, really, about being suddenly and fully out. I was too deep in grief, too deep in guilt, forever—even now—regretful that I wasn’t there that night to pinch his biceps or kiss his abs, to make him laugh, to help him see a future instead of an end.

I mostly hid in those first few weeks and months, crazy with crying, sick of the pity and sympathy. I found myself almost every day in the libraries of local museums and universities, and various branches of the public library. In one of those bookish refuges, a librarian befriended me. Though he never said it, I knew he was gay; and though I never said it, he knew I was too. A knowledgeable man approaching middle age, he saw me for what I was, a young brother of his, a broken one, just out and barely hanging on.

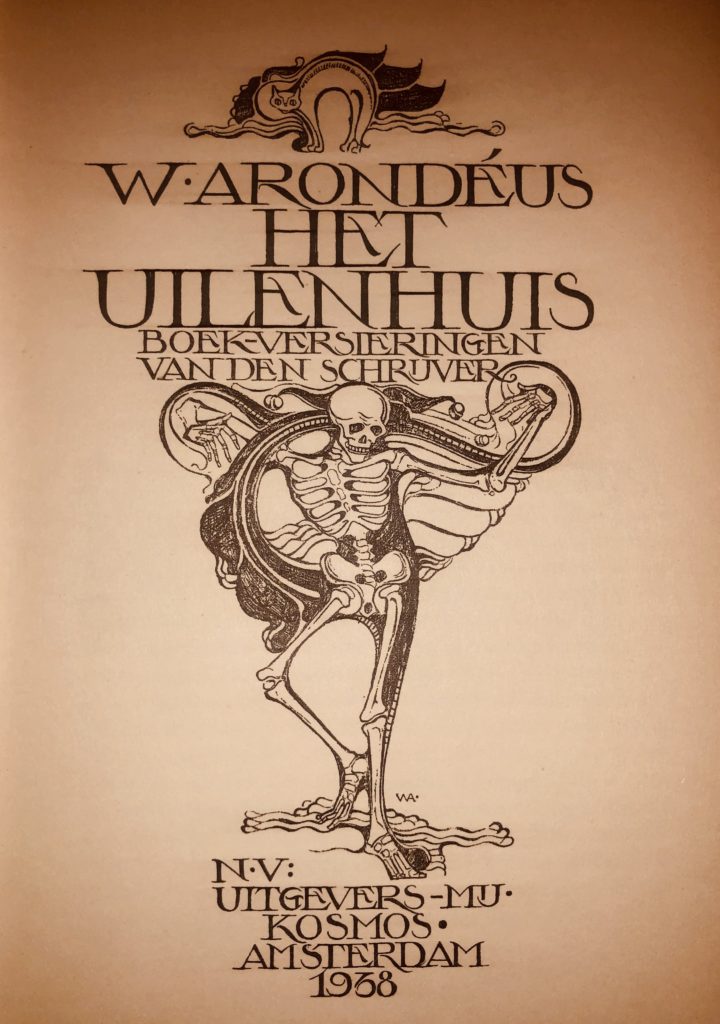

My friend gave me a subtitled copy of the Arondeus movie, which I watched two or three times in a row, by myself in my room that night, learning about Arondeus. He had been forced away by the Nazis, not given a chance to say goodbye. What would he have said, if he’d been given time to properly say farewell to everyone he loved? I do not know.

Nor do I know, though I’ve tried so hard for decades to remember, what Joseph’s exact last words were to me the day before he died. I can’t remember, because at the time I never would have imagined those would be his last words. He, too, left without saying goodbye.

My friend wanted me to hear Arondeus’ final message: “Homosexuals are not cowards.”

Those phantom words of his, hanging elusively out there in the ether, are my goodbye that never was.

In the decades since this story took place, Brian Fehler earned degrees in English and now teaches writing and rhetoric at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas.

Discussion5 Comments

Although I believe I’ve heard you tell this story before, I was glad to encounter it again in this powerful form. It again takes my breath away. Thank you so much for sharing.

Thank you! ❤️

Peter G. Courlas I was so ,moved by your story, i had a lump in my throat !! I experienced a love for 38 years ( married when same sex couples could.) We were completely out for all of those years as a couple.He died 7 years ago of cancer. I treasure those years we made our love and commitment the first priority over our friends and family. I still miss him deeply but grateful our lives were so enriched with each other. Brian you never get over the type of loss we have experienced. Yo just learn to live with it.What a joy you were for each other.

Thank you for sharing your moving story, Peter. Inspirational, too–38 years! I know your heart will always be full of beautiful memories. Much love, Brian

I would be interested in seeing that movie or finding his books. I recently found out that I am his great niece, one of the last who caries that last name Arondus (though Canadianized when my grat grandfather, his brother, immigrated to Canada).