At 58, I outed myself through a series of conversations on Zoom, in the middle of the pandemic.

This happened just a few months after burying my wife and partner of 40 years, whom I’d loved very deeply and who’d suffered greatly from a rare and incurable cancer.

It was a time of intense grief coupled with immense relief at the end of her suffering and at my being able to remove the armature that every closeted gay person wears to deflect and protect. It’s heavy, and hot, and limits your range of motion and emotion.

My wife had known before we’d married, but no one else had. The expansive intimacy we shared worked for me and for us, and we’d spent eight years before marrying understanding the depth and shape of it. Because of her acceptance, I’d always felt out and at home, with myself and her. Put differently, I’d built a home with a big enough closet.

At that point, “gay” was a sensibility as much as a sexual identity, an encompassing feeling of how I would be in the world and not so much who I would be with, i.e., a man. It remained that way for decades. I was able to compartmentalize my queerness into these two realms of being. Perhaps not the healthiest segregation but a necessary one, I felt, as this was in the emerging era of HIV/AIDS.

In that way, Zooming was really a second coming out, though no less consequential for the possible social disapproval, since I’d decided I would publicly be in a relationship with a man, no longer willing or even able to keep my sensibility and sexuality apart. I feared my straight friends might see duplicity, my gay friends, cowardice.

These dramatic circumstances (oh, and I’d gotten a case of shingles) had left me scarred, exhausted, and vulnerable, and I didn’t want any more drama when I shared my news. Therefore, I figured that the social distance and banality of Zoom would be a good option. But I had no idea that Zooming out would be so hilarious.

It’s worth saying that finding humor in the depths of grief may seem callous. Yet, my wife experienced her illness with great grace, and the dark side and the funny side were often one in the same. This rubbed off on me. And since we’d known for a long time that she was dying, I started preparing myself years before for being alone (and out), mostly through mindfulness practice, which helped me experience my wife’s grace in illness as my own. For me, that acceptance became a funny BFF who helped me see that Zooming out meant there’d be no need for the awkward coffee klatches and inevitable, “Well, good for you!” the gay world’s equivalent of the American South’s “Bless your heart!”

I got an even better reaction.

Zoom meetings during COVID had an urgent, distraught quality that prompted serious dialogue. If, for example, the conversation really hit an awkward pause, the person whose understanding (if not acceptance) I sought, could make up an excuse, say she had to end the call to go kill her children, whom she was unsuccessfully home-schooling, Day 155, in the upstairs guest bedroom.

My 86-year-old aunt disappointed me when I Zoomed her my news. It wasn’t so much her response — “This would have killed your parents!” — but her lack of imagination.

“No, Auntie,” I said. “So many other things I did hadn’t killed them. I’m, sure they’d have survived this.”

Some other things they survived: My elopement with someone fourteen years my senior; opting not to buy the modern-day equivalent of a papal indulgence to marry someone Jewish; attending an ultraliberal college where Ronald Reagan had been burned in effigy; buying a German car; serving brisket on Easter; never having children; and voting for Hillary.

Auntie agreed: “Yes, your mother did survive that; I’d totally forgotten about Hillary!”

The backdrops for the Zoom-outs helped break the ice with others. “Did you redecorate?” they’d ask, pointing to the frilly red and white check curtains framing my head.

“No, I’ve rented a boathouse on Cape Cod, to write.” The Dorothy Gale gingham was a bonus.

The whole miasmic mess of my wife’s hospice had taken a toll, and I’d run away from home. I couldn’t walk by the room where my wife had just died without losing it; I had to leave that sad house in a safe Boston suburb. After more than a decade of metastasis masquerading as life, at the end, it had been just us, alone in our immuno-compromised bubble, me holding her hand as morphine melted in her mouth. Now, I sought the solace of the sea.

Losing your partner means losing two lives—the person who died, and the life you shared. And when the new life you’re beginning looks nothing like the one that’s ending—with no recognizable signposts—it’s a fierce rite of passage. The waves crashing outside my window seemed about right.

Grief was my guide through this; humor helped me carry the load. Think Woody Allen debating the meaning of life with a back-packing Bette Midler while walking up a steep mountain path.

My Divine moments included:

- Learning the poetry of dating on Scruff, with its welcoming and affirming, dick pics,

- Discovering that not having been with a man was an excellent qualification for not finding a partner,

- Receiving a crystal butt plug with an embedded violet from a close, straight friend who wanted something to “fit” the occasion, and

- finding more catfish on Cape Cod than cod.

This went on for a while. Then, one March night worthy of The Shining, I got a message from a guy who was, according to Scruff’s locator feature, 865 feet away from me. I pictured a stalker in the woods near the boathouse, not a sexy biologist working at the Marine Biological Lab across the pond. But he had sent a grammatically correct text, a rarity, and that seemed worthy of risking a date.

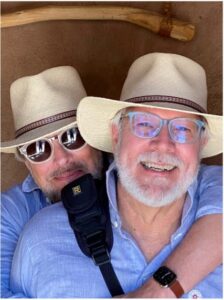

A few dates later, I started to envision a spacious new home with this guy; no closets, just a place where my queer sense and sexuality could live happily together.

Fast-forward a few weeks, where I’m being hazed by my Ph.D.’s lesbian posse. Standing in his kitchen on our third date, I’d been handed a bag of oysters to shuck, something I’d never done. I slipped on the glove, grabbed the shucking knife, and started hacking at the lip of the oyster.

She was staring at me across the kitchen island, arms folded, shaking her head. “You’re doing that all wrong!” Grabbing the knife out of my hand, she said “I’m a lesbian, and we know how to shuck.” “See this?” she continued, clutching the shell, and poising the blade. You probe around! You find the weakest spot! Then you thrust the knife in until you reveal that soft inside part, you flip that over, and you suck out the juice.”

The lesson ended there. I had much to learn about the ecstasies of queer cuisine.

But, in the end, I got the guy. Aw-shucks!

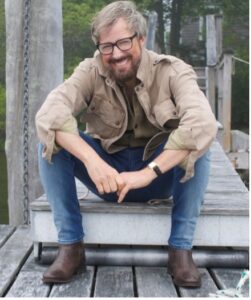

Charles Roussel writes prose and poetry on Cape Cod. He’s working on a memoir about a life of loving many beautiful things, which Van Gogh believed was the source of true strength.

Charles Roussel writes prose and poetry on Cape Cod. He’s working on a memoir about a life of loving many beautiful things, which Van Gogh believed was the source of true strength.

Discussion1 Comment

Great article, Charles! Stop by whenever you’re in Boston; miss seeing you.