British Queer Cinema

British Queer Cinema

Edited by Robin Griffiths

Routledge. 248 pages, $31.95

BRITISH QUEER CINEMA? What’s that? This substantial collection of academic essays appears under a title that is less self-evident than it may appear, in respect of all three of its terms.

Pretty much all the contributors are obliged to discuss the knotty term “queer,” conceding that the word has invariably been applied to Amer-ican and continental European filmmaking, with the single exception of the late Derek Jarman’s oeuvre. They make such a meal of this rather unnecessary problem—establishing what “queer” is, and/or insisting it can’t be defined, and then meas-uring selected movies against sundry definitions and non-definitions—that the reader simply wants to say: “Get on with it!” Ultimately, characters, actors, directors, and writers are shunted under collective umbrella terms such as “lesbian/gay/ queer” anyhow. Everything I found interesting in these pieces had nothing to do with abstract or definitional crises. (Robin Griffiths’ introduction succumbs to that other blight of academia, the tortuous pun, as in: “the history of queerness in British sinema.”)

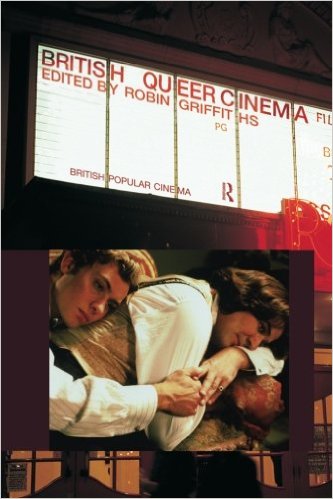

Having said that, the cover photo of Stephen Fry and Jude Law in the bio-pic Wilde still raises an eyebrow. However flexible “queer” might be, it is more customarily invoked to suggest radicalism—formal or thematic—and/or a spirit of dis-sent from the mainstream or the traditional. This flawed, cozy film not only suffered from the inertness of its central per-former but from a lumbering, heterosexual- or family-indoctrinated script.

The term “British” throws up problems less prominently discussed but arguably more interesting. Stars and scripts from “over here” have long ended up in Hollywood, of course, and several American treatments of British storylines are given houseroom. Most successful is Lizzie Thynne’s essay on Robert Aldrich’s The Killing of Sister George (1968), adapted from British playwright Frank Marcus’ play and starring a bawdy West End icon, Beryl Reid, who was entirely unknown in the States. Overall, the funding contexts and implicit understandings of audience reach, sensibility, and so on are too often marginal in this book’s discussions. But Thynne, herself a filmmaker as well as an academic, is a worthy exception. She also discusses at length the role played by production codes, certification, and the censor, all vital material circumstances to many films featuring homosexuality through the last century.

Nowadays, the funding vicissitudes of cinema throw up all manner of peculiar transnational com-binations and oppor-tunities, not least as a result of television’s incursion into the field. Britain’s Channel 4, for example, was a pivotal source of money for the TV dramas based on Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City novels, especially when American channels were put under pressure from right-wing organizations to withdraw. One consequence is that British stars now become “established” on celluloid in very different ways and at very different times from country to country. Ian McKellen was a household name in Britain for decades before cracking it internationally in the U.S.-scripted, -funded, and -filmed Gods and Monsters, where he played the expatriate director James Whale.

A number of essays contrive to discuss the role of casting par-ticular stars and respecting their actual or rumored sexualities, though oddly none draws on gay critic Richard Dyer’s Stars, a groundbreaking 1970’s study of the whole fame phenomenon. In the case of Jude Law, it’s not so much that he’s “renowned for baring his trim, toned physique: his body is routinely offered up in still images as an erotic object of contemplation,” as Glyn Davis argues. That is true of most (all?) Hollywood pin-ups. Nor is it too relevant that “extratextual, speculative gossip re-garding his sexual orientation often circulates subculturally.” The key point is that the three roles which introduced Law to us were variations on the rentboy–sexual opportunist figure. Davis misses a trick in analyzing his contribution to Wilde without reference to the link between his interpretation of Alfred Douglas and the character he played in the first film he starred in, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Then again, that, of course, was an American film, “queer” or otherwise.

Davis’ essay is among the least successful in criticizing its chosen text for its purported conservatism. It is not problematic that director Brian Gilbert’s “camera regularly lingers on beautiful men,” nor that Fry has exhibited “unclear” politics. (True of Renée Zellweger? Ewan McGregor? Most stars, except Schwarzenegger?) Fry has indeed written for the right-wing Telegraph newspaper. So did Dirk Bogarde. What of it? The awkwardness of Wilde resides in its overall handling of the gay theme as conceived by Julian Mitchell (of the more successful Another Country fame). Whether in accordance with auteur theory or simply as an unintended echo of the priorities of film production companies, these essays place hardly any emphasis on the central role played by scripts. Kenneth MacKinnon, for example, spends more time discussing the casting of Vanessa Redgrave in the Alan Bennett–scripted Prick Up Your Ears (1987), the biopic of Joe Orton. Bennett’s (perhaps accident-ally) progressive script deserves a fuller study, especially con-cerning how it upends the prurient drift of John Lahr’s source biography.

A few essays concern fleeting glimpses of homosexuality prior to 1961’s watershed Victim, directed by Basil Dearden. This seminal courtroom drama was the first British movie with homosexuality at its center, and—it would later transpire—a gay actor, too, in Dirk Bogarde. Griffiths’s own contribution is an impressive survey of the role of a number of gay directors—Tony Richardson, Lindsay Anderson, John Schlesinger—in the same decade, in movies with secondary or incidental gay stories and characters.

Lastly, the third term “cinema” is oddly tricky, given the blurring of boundaries between films for TV, cable, and the multiplex. This is particularly important since a number of TV ventures have had inordinate influence upon and resonance for gay representation. Three obvious examples don’t feature in British Queer Cinema, unfortunately: Granada’s much-celebra-ted 80’s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (not even in the selected filmography), Oranges are not the Only Fruit (BBC, 1990), and Channel 4’s Queer as Folk (1999), which inspired its U.S. namesake without resembling it one bit. Still, TV drama is clearly allowed. Gregory Woods gives a useful summary of a number of works addressing AIDS that will not be known to most American viewers. Hettie Mac-donald’s overrated Beautiful Thing (1996), a film much in debt to British TV soap operas, has an essay dedicated to it, though Ros Jennings notes its predictable moves and can only com-mend it for its “positive unoriginality.” Huh?

In some cases, so much space is necessarily given to plot summary that the link between what happens and what a film text “signifies” is rather too immediate. Formal or technical choices can recede. Omissions of all kinds are inevitable in collections like this, and there have been a number of volumes aiming at a more complete “take” on British gay cinema. Still, Derek Jar-man’s career—without equal, and spanning cinema, theatre, pop music, advertising, and television—is discussed only by way of Edward II, in a rather good study by Raymond Armstrong.

As in almost anything written under the aegis of “queer,” there’s a tendency to valorize poorly made or ideologically sus-pect works of radical chic. The execrable Nine Dead Gay Guys (2002), for example, is commended, it seems chiefly, be-cause a lot of people either didn’t see it (poor distribution) or walked out. This is the “radical efficacy” of “queersploitation.’

Among the rewarding pieces in British Queer Cinema, there are also a few dogs. Keith Howes’ “Are there stars out tonight?” meanders incoherently between Rupert Everett, Dirk Bogarde, and Ian McKellen, with such subjective observations as: “Un-like Everett, Dirk Bogarde was a genuine star, at least in Britain, for over a decade.” Here and throughout the book, prose seems not to have been proofread. One of Howes’ sentences runs: “There were Hollywood offers, refused Gigi, and unwisely accepted Franz Liszt’s story.” Elsewhere, Eileen Atkins morphs into “Atkinson.”

Griffiths has edited a volume that will be useful predom-inantly for students and scholars in the field. For all my reser-vations, it opens up numerous areas worth further inquiry, and, of course, the history of gay men and women in British flicks is far from complete. It’s a still moving picture.

Richard Canning, author of Gay Fiction Speaks and Hear Us Out, is the editor of a new book of gay male fiction, Between Men (Carroll & Graf).