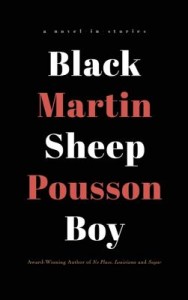

Black Sheep Boy: A Novel in Stories

Black Sheep Boy: A Novel in Stories

by Martin Pousson

Rare Bird Books. 208 pages, $22.

MARTIN POUSSON knows Cajun Acadiana, which he probed in his 2002 novel No Place, Louisiana and a book of poems called Sugar (2005). (Full disclosure: we attended graduate school together.) His new “novel in stories,” Black Sheep Boy, lyrically advances the plot of the earlier novel. The unnamed narrator, full of curiosity about the world, is a young gay Cajun boy chomping at the bit—more than one bit—placed there by circumstance. He speaks, he tells us, with a lisp, but he’s clearly aiming for a life lived out loud. But to get there, he will first have to endure a family and culture for which love is both a generative and a destructive force, leaving no one satisfied with who they are or whom they are with.

Pousson’s novel begins with a book being read out loud, a cautionary tale about a badly behaving boy making a mess of things. The narrator’s mother is mounting what will be a failed campaign of shame, superstition, and suppression. She intends to stamp the Devil out of the boy even as she squeezes the Cajun from her husband, who she thought would deliver her from a life of scarcity. She may be a black-haired, dark-skinned, mixed Cajun-Sabine woman, “a Pentecostal, revival-singing daughter of a voodoo man,” but she is determined to bleach any darkness from both her husband and her child. That she fails so passionately makes this book seductive and thrilling. We learn that her boy swishes, sways, stutters, flaps, and flits. He is charmed, possessed, and dangerous not only to himself but to her plans. His mother senses that her boy cannot survive in this bayou, which nonetheless is so much a part of who he is. This is one of the remarkable things about this book; for all their travails, a strained love seeps through the narrator, his mother, and his antagonists, binding and yet ungluing them. Pousson layers and lacquers sentences in such a way that the reader gets the colors of regionalism through the universal longing for escape. The stories are wild, but his writing never loses the control needed to take these people aloft on their own words, fantasies, delusions, convulsions, and magical histories. There’s a necessary excess, exhalations that breathe the book into magical life. The segments reveal the depths of passion and longing, as Pousson’s characters squirm in their own skin. This book really does cast a spell on you, and the effect is wild and wondrous. Magical realism has moved north to Acadiana, and the spell takes. The book’s structure of short, story-like sections moves us in and out of scenes of the narrator’s life as his changeling persona develops. The chapter titles hint at these transitions: “Revival Girl,” “Wanted Man,” “Masked Boy,” “Altar Boy,” and “Two-Headed Boy.” This is a novel of masks, hidden shames that explode into ecstasy only to creep back in the morning to change again. There is always some force tormenting, teasing, troubling the boy. He is surviving and living to tell the tale in his own terms, strands of pearls and evocative words soaked in the brine of place. This boy loves this place he has left; it left him first, looking askance and judging him unfit. Yet still he unfurled. Almost everyone in this book is possessed, on fire, stamping and shouting and perhaps flying through the air. His mama wants him to be a “solid boy,” but this child is in pieces, fragments that pull together as mysteriously as do the tales themselves. Generously, forgivingly, the boy keeps looking to his mother, who perhaps wittingly forces the “jenny boy” to be not a victim but a herald of change in a place where change is relegated to magic and loss, motivated by resentment, anger, and alcohol. The boy is slowly emerging into a man, but not like his ancestors. As he senses during a Mardi Gras parade: “Every Cajun man was, in some real way, smaller than the man before him.” This boy is on a different route, a twisted path full of language and longing, “humming and hiccupping and howling our way into the wide open night, into the wild and fantastic unknown.” We aren’t guided but sucked whole into his story. The boy, grown up, has come home to a place forever changed by his own spells. He knows all the steps to the dance now. Jeff McMahon is associate professor in the School of Film, Dance and Theatre at Arizona State.