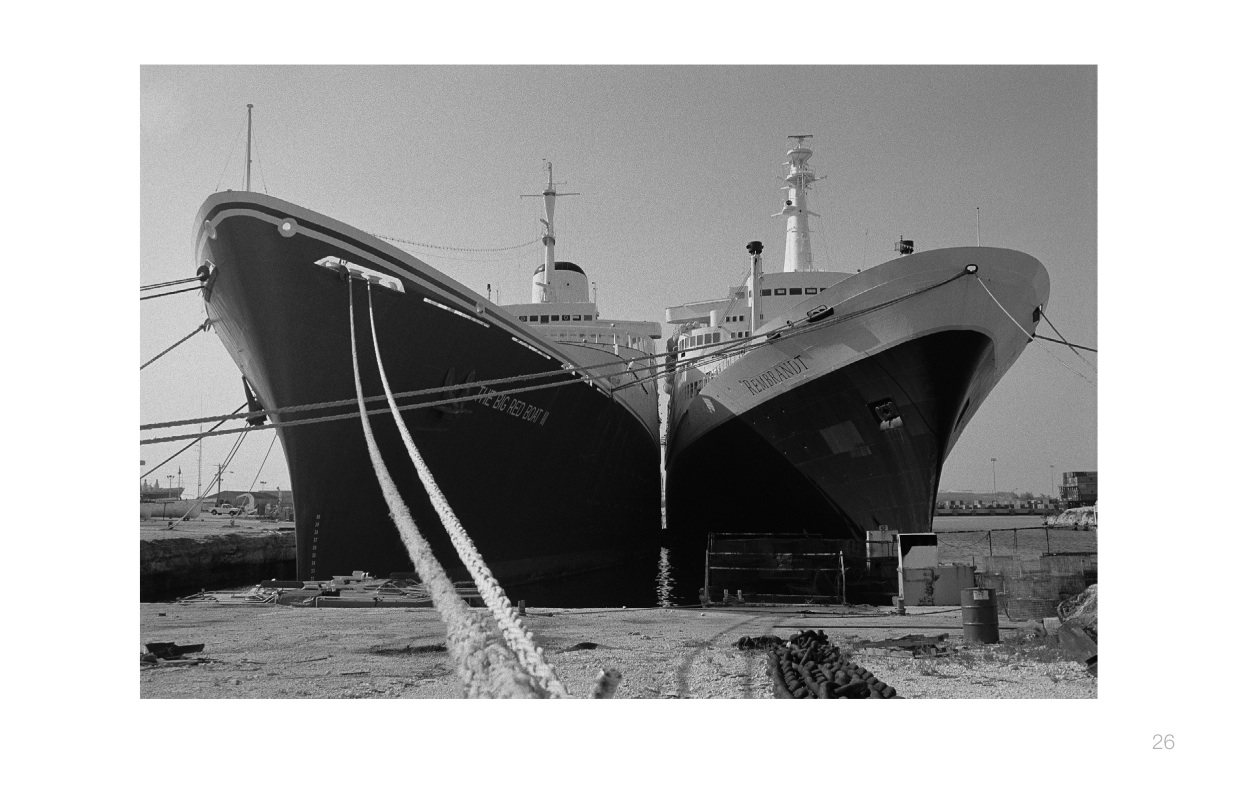

I’M LOOKING at 25 photographs of retired, wrecked masters of the sea, ocean liners laid up and languishing in disuse and decay. These photographs, from Stranded: The Twilight of the Ocean Liner: Photographs by Martin Cox, at the Los Angeles Maritime Museum, illustrate the reverse velocity of technology, steely in these old ships which, like us, are only as good as their last crossing. As an act of honor and salvation, from 2000 to 2005 Martin Cox traveled to various ports in the U.S., Canada, China, and the Philippines during the time when these ships from the middle of the past century were being cut adrift. They had fascinated him as a child growing up in Southampton, England. Here he gives us the titans of his youth, tethered at their final destination.

One might expect that Cox, now living with his husband in Los Angeles, would train his camera, at least occasionally, on the sailor and not the ship. But that has not been the case.

Jeff McMahon, a writer and performer, is associate professor at the School of Theatre and Film at Arizona State University.