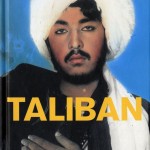

Taliban

Taliban

Photographs by Thomas Dworzak

Essays by Dworzak, John Lee

Anderson, Thomas Rees

Trolley Books (UK)

128 pages (illustrations), $24.95

Arriving in Kandahar in July 2001, photographer Thomas Dworzak intended to ask Afghans to sift through hidden collections of photographs from schools, studies, and families. The Taliban, who had banned photography since taking over in 1996, refused to grant Dworzak a visa, certain he would be “proselytizing.” In December 2001, during the war against the Taliban and al Qaeda, he returned to Kandahar. The photographs he collected were commissioned by Taliban warriors wishing to commemorate their heroism, bravery, and (perhaps less consciously) youthful beauty during the American invasion in the fall of 2001. The soldiers, on the brink of defeat, wanted a record of who they were. Dworzak arrived to sort through the abandoned photos whose subjects, one of the photographers reminded him, were mostly now dead.