ONE OF THE MOST AMAZING PLACES in the world to learn about the gay past is the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London. Almost every gallery contains someone famous and/or fascinating who (in our terms) fell somewhere on the GLBT spectrum. This was especially clear a couple of years ago, when the first piece you saw in the permanent collection was a statue of Edward II and the last piece was a portrait of Ian McKellen.

The NPG, like Boston’s MFA, is one of those museums that constantly moves things around, so that, like the New England soil that brings up new rocks every year, its galleries are always turning up new portraits, including those of gay subjects. So, Edward II is gone now, but soon you arrive in the gallery of the early Stuarts, where there are portraits of James I, his “favorite” courtier George Villiers the Duke of Buckingham—showing off his famously comely legs—and the bisexual bard, William Shakespeare.

Ian McKellen is also gone, but now the last person in the display is the gay playwright Joe Orton. In between, there’s an amazing panoply of GLBT people, including the great 18th-century transvestite, the Chevalier D’Eon; the 19th-century explorer Richard Burton, who shocked Victorian England with a lengthy essay on same-sex love that he appended to his famous translation of The Thousand and One Nights; and Radclyffe Hall, the early 20th-century author of The Well of Loneliness.

The museum is particularly rich in material from the Bloomsbury group, the loosely organized social node of post-Victorian experimenters who transformed British ideas of art, literature, and love in the early 20th century. There are portraits of the revolutionary biographer Lytton Strachey, the great economist John Maynard Keynes, and the brilliant novelist Virginia Woolf on display, as well as lesser-known figures such as Violet Keppel (the daughter of George VII’s mistress and lesbian lover of author Vita Sackville-West).

Just to give you an idea of the collection’s gay riches, the last time I was there, there were some early snapshots on display taken by society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell (the lover of Bertrand Russell) at her country house, Garsington Manor (now known for the summer opera festival). One shows a little group of Bloomsburyites chatting in the garden. The seated, bearded man benignly holding forth is Lytton Strachey. Standing behind him is the group’s cutie-pie painter Duncan Grant, who was Strachey’s cousin—and lover. The strikingly placid and beautiful woman seated to Strachey’s left is Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s older sister, also a painter. Bell and Grant, after a brief sexual relationship, maintained an artistic and emotional partnership for many years, mainly while living at a country house in Sussex called Charleston Farmhouse. Their sexual relationship resulted in the birth of a daughter named Angelica (though Bell was married to critic Clive Bell), but Grant had various other lovers, all of them male. These included, aside from Strachey, Keynes and an author-editor named David “Bunny” Garnett, who later married Angelica—a move considered shocking even by Bloomsbury. The woman to Strachey’s right is Dora

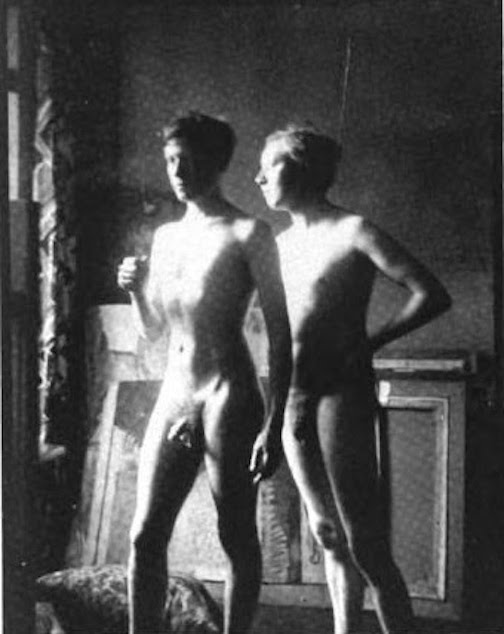

For fun, take a look at the photo at right: a nude of Grant and Garnett together in 1914 (Grant, in front, was 29, Garnett 22), when they were doing farm work together as alternate service during World War I. The young men in the Bloomsbury set took quite a number of nude photos of themselves and each other—another strikingly modern thing about them.

If you’re curious, you can learn more on Oscar Wilde Tours’ Gay London/Gay Paris tour this coming August, click here. The tour includes a tour of the National Portrait Gallery, a walk around Bloomsbury, and a visit to Charleston Farmhouse – a magical place with touches like an unfinished nude of another of Grant’s boyfriends still on the easel.