HOW DID Gertrude Stein, a Jew who was also a homosexual in Paris during the Nazi occupation of 1940–1945, manage to survive—both physically and psychologically—during the Second World War? On the first question, that of physical survival, most of Stein’s biographers have concluded that the head of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Bernard Faÿ, protected Stein and her female companion Alice B. Toklas as the two waited out the war in Bilignin, France, during Maréchal Pétain’s Vichy regime. In an interview before his death, Faÿ claimed to have had Pétain write a letter and to have made frequent phone calls to the sous-préfet of Belley, despite the fact that thousands of non-French “undesirables” were being deported daily by the Nazis with the Vichy government’s help.

While biographers continue to debate Stein’s elusive political sympathies, no one has fully explored the nature of Faÿ’s protection or the exact details of its execution (with the possible exception of Linda Wagner-Martin in 1995’s Favored Strangers). John Whittier-Ferguson grants the existence of Stein’s “problems of allegiance in occupied France” (in his article, “The Liberation of Gertrude Stein: War and Writing,” in Modernism/ Modernity, Sept. 2001), but curiously does not engage in a discussion of such problems in relation to her wartime texts. He writes that Stein was “living exiled from the quiet confines of an imagined and secure self, without an island haven,” and that “[t]o be modern is to be forced … into contact with the irreducible mystery of others. It is to live always in the state of wondering ‘who goes there?’”

Stein’s psychic survival against the backdrop of the Nazi witch hunt is another question, one that can only be explained, in my view, with reference to her identity as a transgendered person. For if Gertrude Stein were to meet with any licensed psychologist today, she would undoubtedly be diagnosed as having “gender identity disorder.” Though she’s been widely regarded as a lesbian, the fact is that she saw herself, in essence, as a man. Her social status was that of a “lesbian” writer, but the code by which she unconsciously lived and which is revealed in her writing reveals a paradoxical existence, the conundrum of a transgendered identity. Like many transgendered individuals, Stein identified with lesbianism, because, as Gay Wachman suggests, writing of lesbian stereotyping in Lesbian Empire (2001), “a negative image can be preferable to a blank when one is struggling with identity.”

Stein’s struggles with gender identity haunt her wartime politics, especially in her two meditations, Paris, France (1940) and Wars I Have Seen (1945), written between 1943 and 1944. In Paris France, though her subject is France during the war years, Stein only occasionally mentions either World War, and does so in an offhand manner in the context of ordinary events. What’s interesting is that every topic she addresses, whether war, fashion, logic, or food, is polarized and pitted against another: peacefulness versus excitement; reality versus perception; women versus men; children versus adults; cats versus dogs; inside versus outside; above versus below. This method creates a linguistic battlefield that is transgendered in nature, because each idea is constantly vying for definition or explication with its opposite—but in vain.

Of her adolescent years Stein writes in Wars I Have Seen: “[T]here was no war and if there was it was not any war of mine.” The wars that were hers were personal battles, because “[s]uch wars as there were were inside in me, and naturally although I was a very happy child there were quite a number of such wars.” Stein consistently writes questions as declarative statements ending with a period. She sees herself as such a construction, as a declarative statement hidden inside a question. The statement, while direct, often reflects the trepidation that the exhausting demands of the transgendered struggle evoke: everlasting competition, opposition, conflict, and contradiction. In another passage she writes: “You ask questions now why in Russia do not the Germans surrender when they are surrounded. And there is no answer except that perhaps they are afraid to.” Stein understands imprisonment and the fear that accompanies it, and though she almost fatalistically states that “there is no answer,” this is one of the few instances in which Stein hazards a guess: “perhaps they are afraid to.”

But for Stein very little changed during war, because she was always at war with herself anyway, which somehow cancelled external events. France’s ability to change its mind toward Germany or the Allies reflected its mutability and mixed emotions about occupying armies. Stein writes: “In one war they upset the Germans by resisting unalterably steadily and patiently and valiantly for four years, in the next war they upset them just as much by not resisting at all and going under completely in six weeks.” Here, Stein deals with resistance and surrender as twin imposters, two sides of the same coin, which deserve the same indifferent response. The passage also speaks to Stein’s obsession with opposites—and her egalitarian treatment of each element—usually accompanied by a cavalier tone hinting at a sadness that there either are no firm answers or that nothing can be done.

But for Stein very little changed during war, because she was always at war with herself anyway, which somehow cancelled external events. France’s ability to change its mind toward Germany or the Allies reflected its mutability and mixed emotions about occupying armies. Stein writes: “In one war they upset the Germans by resisting unalterably steadily and patiently and valiantly for four years, in the next war they upset them just as much by not resisting at all and going under completely in six weeks.” Here, Stein deals with resistance and surrender as twin imposters, two sides of the same coin, which deserve the same indifferent response. The passage also speaks to Stein’s obsession with opposites—and her egalitarian treatment of each element—usually accompanied by a cavalier tone hinting at a sadness that there either are no firm answers or that nothing can be done.

Stein’s experience of war is also noteworthy for her apparent refusal to face its horrors, as well as her inability to commit to one side or the other. While she saw the miseries war could visit upon the populace, she also wrote that “war comes and it has its advantages.” Her prose takes on even darker tones in Wars I Have Seen. At times Stein seems to turn a blind eye to the deportations and persecution going on around her: “Anything can be a dream, and in war it is more a dream than anywhere. Just now they have sent forty thousand people out of their homes in Marseilles, it is so real to me that it is a dream, not that I know any of them.” She recounts the time she turned away a man in tears who appeared to be a resistance fighter, who had come to her for help with a message in a matchbox. Yet she writes quite clearly about the sous-préfet of Belley, who, when the Germans began to increase the deportations in the summer of 1944, warned her lawyer to “tell those ladies that they must leave for Switzerland, to-morrow if possible otherwise they will be put in a concentration camp.” Despite such warnings, Stein and Toklas did not only refuse to leave, they moved to an even more vulnerable position, a manor house in Culoz near a German security checkpoint and railway station.

For all the military surveillance and persecution of both Jews and homosexuals in this era, Stein and Toklas seem to have remained beyond the pale of the Vichy government’s lens. Oddly, no one seems to have questioned Stein about her personal identity or political loyalties. In addition to the obvious advantages of Faÿ’s protection, which, however, seemed to be wearing thin by 1943, I cannot help but wonder if her ability to elude detection is not partially because of a kind of “freak factor” that kept the authorities off balance. For it was not so much her “lesbianism” as her gender transgressiveness that her enemies, like her critics, found unnerving. Stein was often scrutinized in the press for her mannerisms and for her “female masculinity,” revealing uneasy biases and misogyny on the part of her many detractors. Despite Stein’s Judaism, homosexuality, and intellectual standing within the community, as a transgendered person she remained ultimately uncategorizable. In order for an enemy to hit a target, the target must be clearly in sight

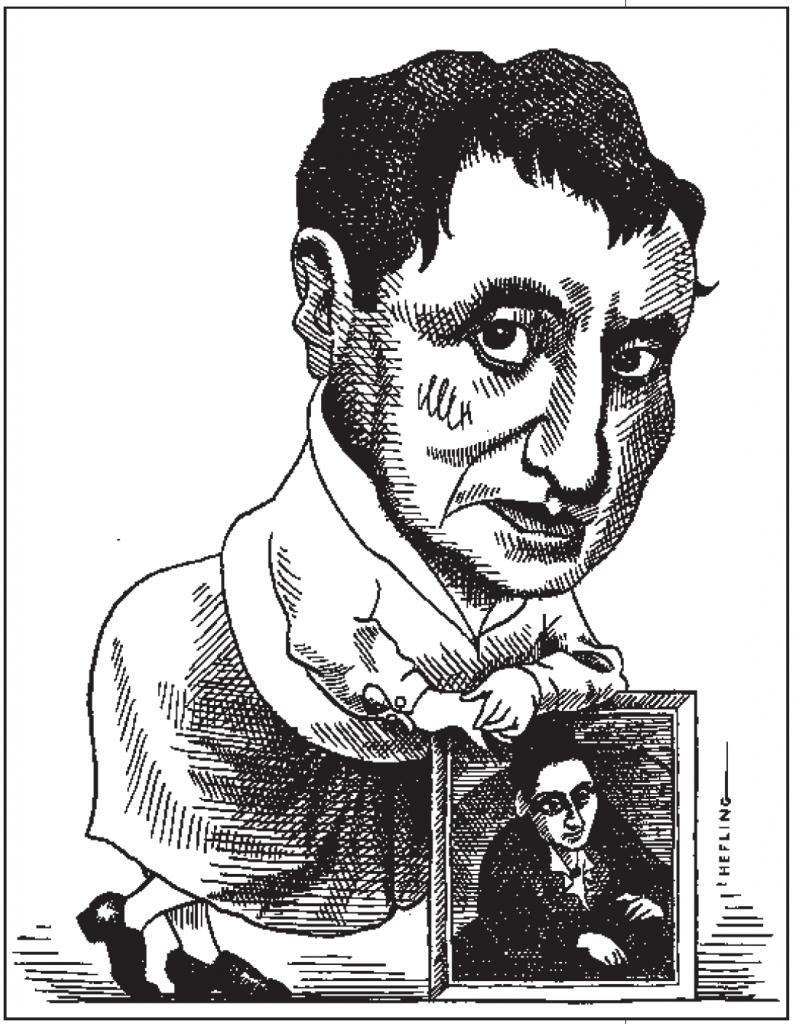

Ideas and objects jockey for position in Paris, France, but they’re often presented as enclosed in outer shells or encased in coverings of less value or authenticity. Thus, for example, of her adoptive homeland she writes that France “came up in my mother’s clothes and the gloves and the sealskin caps and muffs and the boxes they came in.” In a passage on citizenship she explores both the duality and layeredness of identity: “After all everybody, that is, everybody who writes is interested in living inside themselves. That is why writers have to have two countries, the one where they belong and the one in which they live really. The second one is romantic, it is separate from themselves, it is not real but it is really there.” Even in childhood, she reports, Stein envisioned herself inside an oil painting, “where you stood in the center on a platform and all around you on every side of you was an oil painting. You were completely surrounded by an oil painting.” This comment resonates with early childhood memories of many transgendered people, who describe intense out-of-body experiences at a young age, fantasies in which they’re transported or placed inside other enclosures, where they feel happy and whole.

In Paris, France, Stein allowed herself to be who she wanted without fear of negative publicity, and she loves the fact that in France it’s the norm not to talk about one’s political allegiances and beliefs. “One does not tell the political party one belongs to.” Even her servant does not reveal her political affiliation. Of such alliances she writes, “it is not a secret but one does not tell it.” The norms of privacy even apply to one’s physical presence somewhere: “In France they pay attention to you when you meet, but they do not bother you because in between they do not know that you are there.”

In the August 1945 issue of Life magazine, in an article called “Off We All Went to See Germany,” there’s a famous photograph of Stein surrounded by victorious GIs on the terrace of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden, imitating Hitler’s fascist salute. Stein looks comfortable as she always did in the company of soldiers and men. While many critics see the figure of Stein as that of a liberated woman, I see her as a Pétain supporter, a figure with fascist political sympathies housed in the body of a now “patriotic” American. Her pose is that of a political observer with a dual perspective, and her expression in the photo is a natural byproduct of a transgendered identity, conveying a sense of relief over having successfully played both sides in the struggle.

MOST OF THE WORK Stein produced after meeting Toklas, including her war texts, deals with her 38-year “marriage” to Toklas, but her earlier work deals explicitly with lesbian themes. I would attribute these earlier works to Stein’s painful exploration of identity and to her realization that in order to survive she would need to bond with someone of the “opposite sex.” This, of course, would entail bonding with a woman, ensuring that she would have to endure all of the negative consequences of being in an ostensibly homosexual relationship. It wasn’t until Alice B. Toklas moved into the Stein’s household in 1910 and her brother Leo moved out that Stein was able to blossom into the man she truly was.

Critics who discuss Stein in terms of lesbianism assume that this was her route to freedom from patriarchal oppression. In fact, I believe they are perpetuating a lesbian myth. In her groundbreaking study Surpassing the Love of Men, Lillian Faderman writes that “Stein presents herself in many of her autobiographical works as a sensual, humorous lesbian lover who relishes lesbian life and lesbian sex,” and contends that the reason Stein is so difficult to understand is largely due to her wish to disguise the forbidden lesbian relationship. In addition to devices like repetition and the omission of key grammatical conventions such as subject and verb, Stein frequently “refers to the Alice figure as her wife and … gives herself masculine pronouns.” While lesbian authors, painfully aware of censorship and the stakes involved when two women share a bed, often “cross-write,” according to Wachman, they rarely embrace the fundamental tenets of masculinity as fully or as unabashedly as Stein.

Faderman “hopes” that when Stein defines the proper role of a wife in “Didn’t Nelly and Lilly Love You”—“A wife hangs on her husband that is what Shakespeare says a loving wife hangs on her husband that is what she does”—that she’s doing so “with some humor.” I don’t think Stein is trying to be funny at all, beyond the fact that the joke is ultimately on us. And I think the lesbian community is engaging in wishful thinking in believing that Stein is poking fun at patriarchal norms when she asks Alice, “can you obey./ Remember the position. Remember the attention that/ you pay to what I say.”

Lesbian relationships are sometimes modeled on heterosexual unions, though Shari Benstock (Women of the Left Bank, 1900–1940) rightly cautions us not to generalize or surrender to such stereotypes, because “Stein and Toklas shared assumptions about female relationships that were, in fact, antithetical” to other lesbian couples during the Paris years. However, a lesbian relationship that is modeled on a heterosexual union usually manifests itself insofar as one partner assumes a more masculine role and the other partner a more feminine one. These are often referred to as butch/femme relationships or, in the chic language of today, “tops and bottoms.” According to Benstock, in Stein’s day “[t]he term ‘inversion,’ used by these women to describe their own sexual inclinations, meant for them not only the desire for someone of the same sex, but the more pervasive need to duplicate heterosexuality within the homosexual relationship.” But Stein’s work and life defy this categorization, as well.

Stein’s rejection of grammatical rules in her writing was not so much anti-patriarchal, as many critics have suggested, as it was anti-structure and anti-form. As a transgendered person, structure and form had betrayed Stein. Finding herself in a female body, she nevertheless identified with the patriarchy and yearned to remove the covering that concealed a phallus, her true self as a man. In the 1996 documentary film Paris Was a Woman, Stein told novelist Samuel Steward:

Poetry is the addressing, the caressing, the possessing, and the expressing of nouns. When I wrote “a rose is a rose is a rose,” I took the word rose which had lost its meaning. Over the years it had gradually gone away from the object itself. And when I wrote “a rose is a rose is a rose,” I gradually brought meaning back to the word. In other words, I addressed, I caressed, I possessed, and I expressed the word, and I am the first person in 200 years to have done that.

Putting aside Stein’s penchant for grandiosity, her desire to bring “meaning back to the word” and to join structure with essence can be seen as a transgendered person’s dream. Stein’s writing then becomes a cri de coeur to expose her male identity, reveal her true patriarchal self, and become whole.

Jean E. Mills teaches English at Hunter College in New York City.