The week of February 12th 2024, New York City’s first real snowstorm of the past two years transformed the historic Greenwich village into a delicate landscape of icy grounds and cashmere scarves – a reclamation of winter settling in as I made my way to NYU’s Skirball Theater for the latter half of the Queer New York International Arts Festival (QNYIAF). Returning from its six-year hiatus, the festival was also experiencing its own revival of time with a refreshing approach to queering the stage with artists from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Croatia, Germany and the U.S.

Zvonimir Dobrović, the curator of QNYIAF, founder and artistic director of Queer Zagreb and Perforations festivals in Croatia, sets the guiding principle for the festival in opening remarks before each performance. In clarifying insight, Dobrović reminds us that “queerness depends on geography,” its definition shifts based on who and where we are, an inherently political positionality. Each performance stands boldly in its exploration of how queerness is experienced in each respective culture – language and dance is not compromised solely for the American audience members. Rather, the compilation of these acts highlights the interconnection of our queerness across the globe. This is what distinguishes the festival from other queer art performances, at least in the U.S.: it is not afraid to understand and showcase queerness in all the ways it impacts us.

Even the way we experience memory can be queered, as Indigenous Argentinian artist Tiziano Cruz exemplifies in his performative lecture “Conference” or “Three Ways to Sing to a Mountain and Find a Childhood.” While Tiziano stands front and center on the stage, no direct spotlight on him as he watches the audience slowly find the center of the room – we are instructed by the ushers to fill in the seats closest to the stage. This is helpful and earnestly more personal later on, for the more interactive and classroom-esque techniques sprinkled in his performance – passing printed one-pagers down the aisles, twisting and turning to reach over seats, forced to look at our fellow audience members.

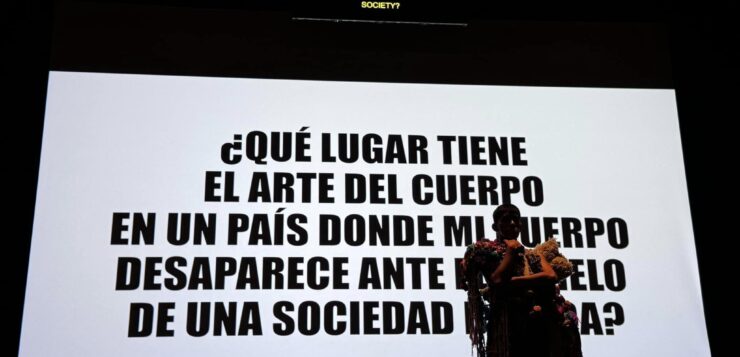

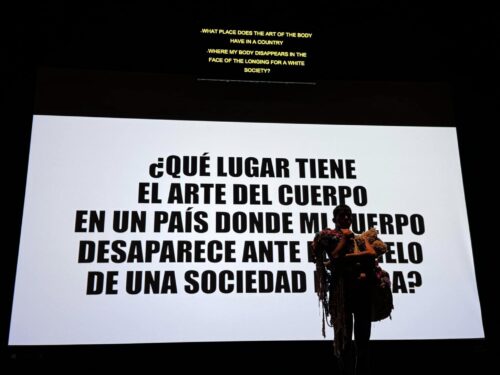

The stage is bare, with the exception of a podium, a saddlebag of colorful props next to Cruz, and his honest invitation into his memories with the remark, “All that you see is all that I am. I have left everything due to poverty.” Wearing a white cropped tee that says, “this is not my life this is theater” Cruz begins his performance as an intimate lecture with a large white projector screen asking: “QUE LUGAR TIENE EL ARTE DEL CUERPO EN US PAIS DONDE MI CUERPO DESAPARECE ANTE EL ANHELO DE UNA SOCIEDAD BLANCA?,” which translates to: “WHAT PLACE DOES THE ART OF THE BODY HAVE IN A COUNTRY WHERE MY BODY DISAPPEARS IN THE FACE OF THE LONGING FOR A WHITE SOCIETY?”

Cruz answers his own question by way of evidence: a photograph showing his late sister who passed away due to the neglect of the American healthcare system and a younger version of himself – his entire face covered with a bag. This is not a curated photo, but carries an emotional weight as a silly and self-fulfilling prophecy for his role as an artist in his family and community. This reveals how his body, which he offers us in tactile ways, is also an extension of his art.

Cruz’s “Conference” was both a lesson and a telling of vulnerability as a means to resist colonial mechanisms of erasure. Through each item in his qepes – (or saddlebag, in ) Cruz remembers himself and the livelihood of his Andean culture, alongside us. Ranging from cajas, a musical instrument, to a Quipus, constructed of primarily rope and hanging cords of wool and which were later used to quilt blankets that covered his family in the winter. At the end of each act with the object, he would put it over his head (a nod to his younger self) and kneel to the stage: which in an hour, had transformed into an altar of collective memory. The generosity of his performance doesn’t elude the reality of Indigenous erasure rather brings us into intimate relationship with his land through creating new knowledge – a combination of stage performance, personal narrative and research as all avenues to preserve a memory, but perhaps something more. He begs the question, what happens to your livelihood when it becomes endangered? Cruz actively creates his memory and lineage, part necessity, part ritual, both of which are inherently queer, allowing him to assert agency in a system that is working so hard against him.

Dobrovic and I spoke briefly at the end of the festival’s closing performance about his choice for ending such a versatile week in one of the more straight-forward, familiar rituals of art we’ve seen as theater-goers but also as people: the act of paying tribute. “It was the perfect funeral” was the takeaway from not only his curating choices, but the audience’s overwhelming agreement with that sentiment. The Raimund Hoghe Company, in “An Evening with Raimund” brought the festival to an emotional, almost spiritual place.

This movement piece revisits choreography fragments over the course of Hoghe’s life — a renaissance man born with a spinal deformity which courageously informed his dance pieces of bodily limitations. As a member of Gen-Z, I stood out from this crowd in more ways than one — but it became immediately clear that the amount of people who showed up were in deep reverie and obligation.

The seven dancers in the dance company, all dressed in business casual clothes, stood in a straight line at the very back of the stage and slowly made their way up to the front in unassuming, free flowing ways to wash one another’s hands. The tenderness and organization of this homage told me that I was witnessing something important. The dancers flitted in and out after this opening ceremony, dancing to sound bites of his documentaries, sweeping orchestral pieces and classics even I recognized, like “Singin’ in the Rain.” Despite my unfamiliarity with the concept of a , there was a visceral entry point as I became increasingly present with my own body as I paid rapt attention to the dancers’ unconventional choreography. Whole pieces performed on the floor or two person acts where one is leading the other’s spine was all at once new and mundane.

The striking sentiment of it all left me grateful for what both queerness and a performance of a ritual can give: a collective truth. I walked away from QNYIAF with bright hopes for what the stage can still reveal to us. This sentiment was echoed in an astute comment from Dobrovic at the beginning of the festival, when he explained how, sometimes the color of our skin makes us more queer than our sexual orientation, which is a resonant reminder that queerness is anything outside of normalized, societal conventions. We have a responsibility as a queer community to bear witness to this truth – a process that Tiziano Cruz regards as ritualistic.

Sarah Drepaul is an Indo-Caribbean nyc native artist merging poetry and filmmaking to rethink how sexuality, spirituality, and memory resides in the body. Her work queers the notions behind archival as the truth, in an effort to understand film and writing as a liberation practice. Sarah’s projects have screened at the King Manor Museum (NYC), Queer Women of Color Film Festival (San Francisco), TwelveGates Art (Philadelphia) and more. Her work has been supported by the VelvetPark NYC Residency, PERIPLUS Writing Collective, BlackStar Film Fest and others. A practicing intimacy coordinator and producer, she believes vulnerability is essential for our collective liberation.

Sarah Drepaul is an Indo-Caribbean nyc native artist merging poetry and filmmaking to rethink how sexuality, spirituality, and memory resides in the body. Her work queers the notions behind archival as the truth, in an effort to understand film and writing as a liberation practice. Sarah’s projects have screened at the King Manor Museum (NYC), Queer Women of Color Film Festival (San Francisco), TwelveGates Art (Philadelphia) and more. Her work has been supported by the VelvetPark NYC Residency, PERIPLUS Writing Collective, BlackStar Film Fest and others. A practicing intimacy coordinator and producer, she believes vulnerability is essential for our collective liberation.