“First, can I go outside and grab a quick smoke?” Bruno Isaković asks after we quickly shake hands. I am following him out the lobby of the Skirball Center for the Performing Arts at NYU to continue the discussion we started a week ago, over video chat. It’s an hour before the Queer New York International Arts Festival (QNYIAF) is about to begin, which brings together an assortment of global artists to explore queerness through lectures, theater, dance, and multimedia installations spread over eleven days. And includes a performance piece by the Croatian-born performer and choreographer, Isaković.

A long-running production curated by Croatian Zvonimir Dobrović, the artists have been invited by Skirball to present the QNYIAF in the city following a six-year hiatus, a gamechanger in terms of recent efforts for visibility and institutional support. Isaković is looking forward to seeing if the move from the slightly looser environs of previous years, like either the LaMaMa Experimental Theatre Club or Abrons Arts Center to the NYU campus, will attract a different type of audience. The slate of performances is meant to expand the conversation beyond the lens of gender and identity to issues of race, class, social dynamics, and different types of marginalized communities. Isaković still finds it a far-out idea, for this little Croatian festival to show up and address these topics in New York, the town, as curator Zvonimir Dobrović likes to refer to, as the place that invented the term ‘queer.’

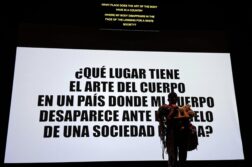

Isaković is represented on the bill by two distinct works. One is the dance piece Kill B., made with frequent collaborator Mia Zalukar, which riffs on Quentin Tarantino’s revenge epic Kill Bill to examine the power dynamics of Isaković and Zalukar’s working relationship. The second piece is Yira, yira (Cruising, cruising) – a devised theater piece co-directed with Nataša Rajković, centering around the stories of four Argentinian sex workers.

As we stand across from Washington Square Park, Isaković pulls a hand-rolled cigarette from a crumpled packet of Bali Shag tobacco. He’s just finished adjusting the staging of Yira, yira, and making minor tweaks to retain the intimacy of the show for a venue this spacious before it plays to a New York audience for the first time. Drawn from the lives of the four performers, the piece interrogates the complex intersection of the social and economic realities of the performers in very personal terms. In discussing the show during our previous conversation, he said “I wouldn’t say that Yira, yira is about sex work, but Yira, yira is about public space, money, love, sex, pleasure, and love but through the vision of a sex worker.”

Isaković has performed frequently in New York over the past decade, an experience he finds to be both terrific and uniquely challenging. New York crowds are more receptive, more vocal, he tells me, more interested in staying after a show and discussing the work, in contrast to his home in Croatia, where the audience files out after a piece is finished. Later this evening, a healthy number of spectators, including iconic performance artist Penny Arcade, will stay for the talkback with the cast and creators.

While he’s built a sturdy body of work over the past two decades as a performer and choreographer, Isaković didn’t begin training from early childhood to be a dancer. His path took him from partying at raves as a nineteen-year-old to a formal course of study — “bribed” as he put it— by one girl into attending class at the same age. He left Croatia to complete his studies, ultimately graduating with a degree in contemporary dance from the Amsterdam School of the Arts. After six and a half years in Holland, he returned to his native Croatia and resumed performing with his first teacher and mentor Ana-Maria Bogdanovic, where he started creating original works.

He remembers it was liberating early on to be onstage and to be applauded for what he loved to do. A gift, he says, to be embraced and accepted by audiences. Especially as his work deals with subjects that matter to him personally and politically. “I cannot avoid it; I think I have a problem,” he says with a laugh. He’s always had a sense of fighting for something in his work using it to process difficult ideas, his art and activism intrinsically linked.

Returning to themes of gender and sexual identity in his artistic practice, he remembers one review of one of his stints in New York that said something like, “Isaković is back, and he’s preoccupied with nudity.” Still, that has become a throughline, in a way, in his body of work. It was his show Denuded which he performed across five continents. It was that work which evolved, expanded, from a solo to an ensemble piece, testing the elasticity of its central idea, an exploration of breath and tension. He was able to expand that preoccupation to multiple bodies, bodies of different age, size, and gender.

Reflecting on his work in workshops and talkbacks, Isaković notesIn the town of Arequipa, Peru, he conducted a workshop open to professional performers and non-professionals alike— teachers, bankers, food service workers, people from all aspects of life — who came to spend their free time discussing and reflecting on the relationship between body, breath and nudity. Those who were typically viewers became the willing participants, “stripping” themselves, physically and psychically. He attributes their openness to being connected to their environment, and to aspects of Indigenous culture. By contrast— in Tokyo— in the same set-up, it was bodily shame that dominated the conversation.

Currently, Isaković is developing two new works for performance. The first, in a more humorous vein, with his other frequent collaborator Ana Mrak, on the topic of failure; the fact that they’ve fumbled several attempts to get together to rehearse the piece means “we’re in the key of the work,” he says laughing. The other piece about the body and public perception, and how one feels one’s body in different circumstances and environs.

In addition to choreography and performance, Isaković works as a graphic artist and web designer, which offers him the perfect balance, and a steady income to support his artistic pursuits. In fact, it paid for a sizable portion of his studies in Holland, where he created websites and online portfolios for fellow artists.

When we first chatted over video call, I commented on Isaković’s choice of a virtual background: a tranquil Japanese tea Garden framed by a blush of cherry blossoms. He has an affinity for Japanese art and culture form time spent working there. Along with friend and collaborator Zvonimir Dobrović, he’s amassed a sizeable collection of Japanese Shunga, or “spring pictures,” a genre of woodblock prints depicting various erotic entanglements; and they co-curated an exhibition in Zagreb, and plan to continue to collect and exhibit pieces throughout Croatia. He even has one of the Shunga images as a tattoo, he tells me, after finishing his smoke. “They’re called the gods of Intercourse,” as he shrugs off his coat and rolls up the sleeve of his tight, olive-green t-shirt, exposing the two figures—the personification of an elderly penis and vagina, with sagging, rotund bellies, standing arm in arm–inked in black on his bicep.

“I always feel empty,” Isaković says when I ask how he manages the end of a show. It may have been presumptuous, with the festival just starting, but I was curious if he had any rituals to recharge or decompress afterward. He draws the comparison between that feeling and the comedown, the emptiness experienced after a break-up, or the end of a party, alluding to his techno youth. Explaining the churn of emotions followed by the absence, he seems to have made peace with the ephemerality of the process, landing at a rather Zen place. “Then it doesn’t matter anymore, and you have to start something new.”

Mike Dressel lives and writes in New York. His work has appeared in publications such as The Berlin Review, Warm Brothers, Bachelors, and Chelsea Station, among others. He previously reviewed the exhibition “Queer Maximalism” for The G&LR.

Mike Dressel lives and writes in New York. His work has appeared in publications such as The Berlin Review, Warm Brothers, Bachelors, and Chelsea Station, among others. He previously reviewed the exhibition “Queer Maximalism” for The G&LR.