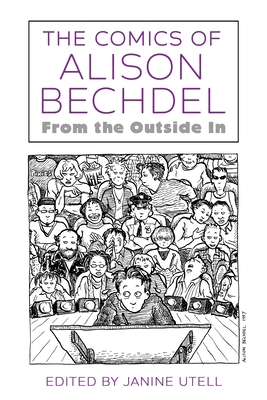

The Comics of Alison Bechdel: From the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel: From the Outside In

Edited by Janine Utell

Univ. of Mississippi. 282 pages, $30.

ABUNDANT MEMORABILIA from when she was only three years old confirm Alison Bech-del’s penchant for sketching line images of people and situations. She learned to read soon thereafter, launching the second faculty that would become the basis for her extraordinary career as a narrative cartoonist. The Comics of Alison Bechdel: From the Outside In, edited by Janine Utell, contains essays by sixteen scholars in the fields of comics studies, gender studies, and popular culture. Bechdel, who lives in Vermont with her wife, artist Holly Rae Taylor, was awarded a Mac-Arthur Fellowship in 2014. This is the first book to focus entirely on scholarship about her major works: Dykes to Watch Out For, Fun Home, and Are You My Mother?

Utell’s introduction neatly summarizes Bechdel’s accomplishments. Born in rural Beech Creek, Pennsylvania in 1960, she went from nonstop sketching as a child to earning a bachelor’s degree in studio arts and art history at Oberlin College before moving to New York City to become a cartoonist. In addition to her zeal for drawing, Bechdel knew early on that she loved women. What eluded her was how to make a career that would take those two realities into account. Browsing through the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in Greenwich Village in 1981, she happened upon a trove of comic books by gay and lesbian artists, and the chance discovery inspired her, in her words, “to apprehend the rich, transformational quality of lesbian experience and get it down on the page.”

Soon Bechdel’s professional career took off. From single-image cartoons, she began drawing what became the serialized and widely syndicated comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. The out-but-lonely cartoonist populated the strip with wildly original characters, among them: an alter ego, Monica (Mo) Testa; Mo’s lovers Harriet and later Sydney; the bisexual woman Sparrow, who has a child with mild-mannered, progressive Stuart; and Lois, an irrepressible “polyamorous genderqueer drag king,” in Utell’s description. Dykes to Watch Out For portrayed “hilariously particular insights” from the feminist lesbian community, with scenes that ricocheted smoothly from uninhibited lovemaking to heated political argument. The enormously popular series ran from 1983 to 2008 (and was briefly resurrected in 2017 following the election of Donald Trump).

While still producing the comic strip, Bechdel started work on her graphic novel Fun Home, a memoir about her childhood, her development as an artist, her awakening as a lesbian, and her closeted father’s suicide. Published in 2006, the riveting memoir was made into a musical that won five Tony Awards, including Best Musical. Bechdel’s second graphic memoir, Are You My Mother? appeared in 2012. The author structured this story about intense mother-daughter struggles using a 6’ by 4’ chart on the wall. Referring to psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s dictum that “the father must be murdered, but the mother can be dismantled,” she has commented elsewhere that it’s “a lot easier to murder someone than to dismantle them.”

While still producing the comic strip, Bechdel started work on her graphic novel Fun Home, a memoir about her childhood, her development as an artist, her awakening as a lesbian, and her closeted father’s suicide. Published in 2006, the riveting memoir was made into a musical that won five Tony Awards, including Best Musical. Bechdel’s second graphic memoir, Are You My Mother? appeared in 2012. The author structured this story about intense mother-daughter struggles using a 6’ by 4’ chart on the wall. Referring to psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s dictum that “the father must be murdered, but the mother can be dismantled,” she has commented elsewhere that it’s “a lot easier to murder someone than to dismantle them.”

Essays in The Comics of Alison Bechdel examine the groundbreaking contributions she has made to graphic narrative as an art form, her depiction of characters’ “multiple selves” at different times of life, and the “choreographic” method she uses to construct comics panels. Several of the most resonant essays shed light on deeper questions, such as what Bechdel aims to do in her comics, how she approaches her work, and what are the sources of her extraordinary appeal.

For example, “The Hospitable Aesthetics of Alison Bech-del,” a sprightly paper by Vanessa Lauber, looks at Bechdel’s self-described early goal, which was “to reach a broader audience while staying radical politically.” Lauber finds evidence of this aim in Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun Home, and shows how those works invite readers into a “relational space,” a notion borrowed from performance art. Here the artist uses her characters, Lauber says, to expose tensions with personal and political weight. She points out that Bechdel invites readers to be her collaborators by picturing themselves inside each comics panel. This boldness holds risks, as hinted at by The Comics’ cover cartoon, which depicts the cartoonist at her easel onstage, pen in hand, facing away from a packed theatre audience. She is sweating—maybe wondering how the polyglot assembly will react to her sketch.

A paper by Smith College professor emerita Susan Van Dyne titled “Inside the Archives of Fun Home” explores how Bechdel approaches her craft. To accomplish this she interviewed the artist in the vault at Smith where, as luck would have it, the archives for Fun Home are stored. Bechdel reports that her purpose in writing Fun Home was to “re-inhabit her father’s consciousness and see herself through his eyes as a route to self knowledge.” The process took seven years. Bechdel kept a daily work log for the first year. At the start of each work session she retyped one of the letters her father had sent while she was in college, the better to imagine what was on his mind. She pored through boxes of personal and family artifacts such as photos, diaries, datebooks, tickets, and fliers. She posed for hundreds of images of herself and of her father, often drawing from the resulting photographs. Van Dyne praises the arduous “memory work” that allowed her to create “the father who would embrace her.”

Bechdel’s wit, inventiveness, and drive are clear, but what accounts for her strong and expanding appeal? Cultural researcher Natalja Chestopalova finds an answer in the ability to “provoke new dialogues”: exchanges that prompt readers to connect her “generational and familial trauma” with their own experience. The scenes Bechdel recreates in Fun Home are not heartwarming, she says, but they do strike chords of recognition. Chestopalova describes how Bechdel came to realize her father was a “gay man with a hetero-normative family,” and the anguish she felt upon realizing that he took his own life shortly after she came out to him.

The Comics of Alison Bechdel sheds light on how the artist has shown LGBT and mainstream readers new ways to understand human connection. In Utell’s words, Bechdel’s scenes “enact in everyday life the idea that to be intimate is to accept others in recognition of both their difference and their humanness.” Occasional jargon can be tough to digest, but the essays overall offer well-researched takes on this superlative comics artist, and identify fresh areas for future study.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer living in Cambridge, Mass.