In a recent and unexpected turn of events, I received a call from Annie O’Neil, a documentary filmmaker. She told me that I’ll Miss You Later, a collection of my poems written during the AIDs epidemic, made her cry. She read the book on Zoom to a group of people who fund her projects. They came up with the money for her and a film crew to come to New York and interview me. Would that be okay?, she asked.

Somewhat stunned, I agreed. Two weeks later, I found myself in my studio apartment, sharing a range of anecdotes about life during the pandemic. I talked for the first time about being a member of an anonymous support group for advanced cases who had decided to end their lives themselves and needed someone present to make sure their exits went as planned. That story led to another I had never told anyone — how Roy Cohn saved my life.

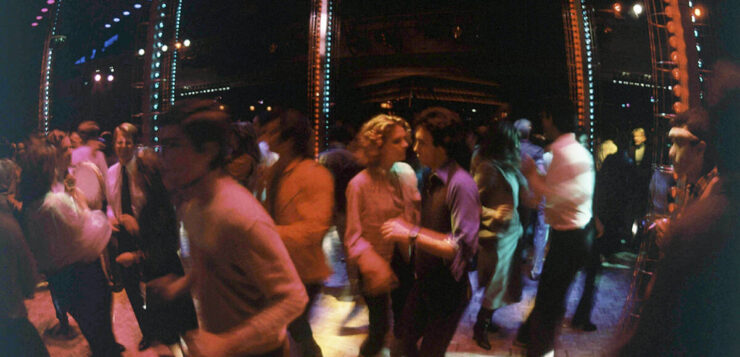

In December 1979, I was leading a somewhat rarified downtown Manhattan party-world life. I was a poet, writer, editor, bartender, and occasional model. The bar I worked in closed around 2 a.m., which meant that after a shift – I had ample cash, and it was peak time to head to Studio 54. I was having great sex with one of the bar backs and would show up to wait for Gregg (with three G’s) to finish his shift.

It was an alternate reality, glittering and drug-fueled. I seem to remember Liza and Bianca floating by, on their way downstairs to ‘VIP Land.’ I was hanging out at the bar, waiting for Gregg. I had scored some coke and was looking forward to an evening of dancing and general madness.

A friend came over and told me that Perry Ellis wanted to meet me, and, of course, I thought, “Why not?” Which is how I found myself in a gaggle of cheekbones and 8% body fat. I heard a voice say, “…and this is Roy Cohn.”

Our eyes met. I remember his icy reptilian stare, but, more importantly, I could feel a shiver go up my spine. Coming from a politically-engaged family of liberals, I was now officially face to face with the closeted gay Antichrist. The Roy Cohn who came to prominence during the McCarthy hearings, targeting government officials and cultural figures not only for suspected Communist sympathies, but also for alleged homosexuality. The Roy Cohn, who was New York’s mob lawyer of choice, Studio 54’s fixer, and mentor to a young Donald Trump. The Roy Cohn later of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which portraying him as a closeted, power-hungry hypocrite haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg as he denies he’s dying of AIDS.

I think I mumbled something that sounded like a hello, but I was hearing a loud voice in my head (possibly my father’s, maybe God’s) telling me, in no uncertain terms, that, if I was being introduced to Roy Cohn, it was time to leave. My life had taken a wrong turn.

So, I left. I don’t remember cancelling my night with Gregg, but I did get myself into a taxi and made it home. I then spent three days meditating (it was also the beginning of my Zen period), after which I decided that I needed to make a dramatic change in my life. No more drugs. No more disco. And no more sex. … At least, for a while.

The while became a year and, with the holidays back in full blast, I realized that I had gone a year without sex or drugs. I immediately decided that enough was enough and went out, getting high and laid. And then went another year without. By the time Christmas of 1982 rolled around, AIDS had started to make its presence known, and life in New York, along with Studio 54, darkened.

So I found myself telling a camera about how Roy Cohn had saved my life — because, during the two years when the virus was at its most transmittable and when I would have been at my most enthusiastically sexual, I was celibate. It’s pretty much the only reason I can come up with as to why I’m still here.

Fast-forward some forty years later: COVID-mandated sheltering in place over the spring and early summer of 2020 awakened something familiar — a sense that every day brings with it a numbing death toll. Also familiar was the rage directed at a government doing the worst job possible, characterized by a callous lack of concern last seen during the AIDS epidemic.

Along with my déjà vu, anger, and despair came another familiar feeling— a desire to dig in my heels, a determination to do something, anything— so, isolated in my apartment, I decided to prepare for the inevitable, and began to update my will, investigate body donation, and let go of as much detritus-in-waiting as possible.

I also began reading and shredding the forty years of journals and letters I had accumulated in an old wooden box, starting with my move to Paris in 1971 when I was determined to be a novelist and find love. I returned to New York in 1977, and journal entries became erratic, due to a late-night existence anchored in Studio 54 and The Saint, a pharmacopeia of recreational drugs, and as much NSA sex as I could manage. Then, starting in 1986, everything became about AIDS.

I found a small pocket notebook with a torn red cover, unwinding wire binding. I kept it during the worst years of the AIDS epidemic as a help in compiling resources and organizing memorial services, of which there were 38 (one for my unbearably hot Gregg with three G’s), the last one in 1997.

There were notations and contact information for relatives, newspapers, gay-friendly venues — many places and business that refused to deal with anything AIDS-related — florists, caterers, ministers, rabbis, a rebel Jesuit and a terrific Wiccan priestess — as well as scribbled notes to self, such as “family is Southern Baptist ODG, get rid of porn”; “F. hated sonnets”; “Sondheim again! write something about Into the Woods and urban mythology.”

Some of those notes-to-self eventually became poems, a few of which — much later — made solo appearances in a range of publications, including The G&LR. I found twenty short poems I had written over eleven years, based on what I had jotted down while gathering details of my friends’ lives. I put them together in the chronological order they had suggested themselves — recreating the context that inspired them. I’ll Miss You Later is the result.

James W. Gaynor is the author of Everything Becomes a Poem, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice in 61 Haiku and I’ll Miss You Later. He lives in New York City.

Discussion7 Comments

Once again, the great James Gaynor’s unique view of life reminds us to listen to our inner voice. There are Roy Cohns all around us. Thank you, Jim, for this wonderful story. Loved “I’ll Miss You Later.”

I love this James, brought tears to my eyes. And made me smile – of course. SO very you.

What an incredible story and a pivotal moment and time in your life. Thank you for bringing this story to life and sharing it with us all.

I wouldn’t think it possible, but the context from the article gives the poems in the collection additional and deeper feeling.

I love this story! I had an amazing time designing I’ll Miss You Later, and this is one I hadn’t heard.

Well written and interesting. A powerful example of how the law of unintended consequences can significantly impact one’s life.

Reading James’ writing transports you into another world. You can almost smell the cigarettes and sweat and see the dark purple lights against the disco walls. A master storyteller that envelops you in his prose and then releases you to begin researching rabbit holes in history.