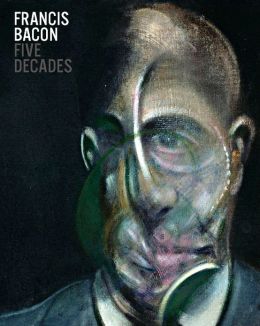

Francis Bacon: Five Decades

Francis Bacon: Five Decades

Edited by Anthony Bond Art Gallery of New South Wales

240 pages, $65.

THE DATES of painter Francis Bacon’s birth and death (1909-1992) fit so snugly within the twentieth century, and his canvases are so uniquely of their time, that it almost seems he was predestined to become who he was. Of course the atheist Bacon would have laughed at that conceit. Yet it didn’t take long for critics to realize that Bacon’s work was a signal achievement, and he’s now counted as one the 20th century’s most important painters. He’s also one of its most recognizable; there’s no mistaking a Bacon painting.

His work was almost exclusively focused on the human form. With their hauntingly bulbous, smeared, and distorted bodies and faces—the latter often punctuated by the disconcerting clarity of a screaming mouth—Bacon’s forms echo some of the most memorable and disturbing images of the last century. One is reminded of photographs of World War I soldiers, horribly disfigured by mustard gas; of the famed Odessa steps sequence of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin; of Picasso’s Guernica; of Adolf Eichmann in his glass booth in Jerusalem. These associations are not accidental. Bacon admired the work of Eisenstein and Picasso (among many others), and his cluttered studio contained thousands of photographs (including many of Hitler and the Nazis), a store that he mined for the motifs that appear throughout his paintings.

Bacon discouraged any biographical reading of his work, but of course critics and scholars can’t resist the exercise—and the painter’s life did have its share of drama. What’s more, Bacon’s homosexuality, his history of intense relationships with troubled lovers, and his sadomasochistic leanings clearly inform the menacing quality of so many of his images.

Although he was born into financially comfortable circumstances, the young Bacon lived through the tumult of the Irish “Troubles,” World War I, and the Great Depression. He also had a particularly difficult relationship with his father, who beat him often and enthusiastically, episodes that Bacon later said produced a distinctly sexual response. (One wonders if the same could be said of his father.) Photographs of the young Bacon show a decidedly attractive young man: he had soulful eyes, sensual lips, and a boyish quality that served him well in attracting the older artists who later became his mentors. His beauty probably played no small part in tempting the rustic stable hands (employed by his father) who were his first sexual partners.

Francis Bacon: Five Decades, published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales to coincide with its exhibition marking the twentieth anniversary of Bacon’s  death, is a handsomely produced survey of his long and remarkably consistent career. Editor Anthony Bond includes an essay by Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels that enumerates Bacon’s connections to Australia (his father was born in Adelaide and the Bacon surname was prominent there in the 19th century) and his debt to his Australian mentors. The book also contains a fascinating series of photographs and an essay about Bacon’s Reece Mews studio, a chaotic hoard that was painstakingly preserved and transported wholesale to a Dublin museum after his death.

death, is a handsomely produced survey of his long and remarkably consistent career. Editor Anthony Bond includes an essay by Martin Harrison and Rebecca Daniels that enumerates Bacon’s connections to Australia (his father was born in Adelaide and the Bacon surname was prominent there in the 19th century) and his debt to his Australian mentors. The book also contains a fascinating series of photographs and an essay about Bacon’s Reece Mews studio, a chaotic hoard that was painstakingly preserved and transported wholesale to a Dublin museum after his death.

The book is organized chronologically, and Bond provides a tidy summary of key events in the artist’s life during each of the five decades. Bond’s notes provide illuminating and sometimes titillating details. For example, in the 1950s, Bacon befriended Allen Ginsberg in Tangier and the poet asked the painter to do a portrait of him having sex with his boyfriend. This never happened—but it’s certainly intriguing to think about what kind of canvas would have emerged. Bacon, incidentally, was also a friend of another prominent Beat writer, William Burroughs.

Those familiar with Bacon’s work are probably aware of the important role that his lover George Dyer played in his life and his art. (This relationship was memorably depicted in the 1998 film Love Is the Devil, with Daniel Craig playing Dyer.) Bacon met Dyer in 1963 under rather strange circumstances—Dyer was trying to break into the painter’s home. So began a relationship that lasted until Dyer’s suicide in 1971. It’s fair to say that this thief-lover became Bacon’s obsession. After Dyer’s death, Bacon broke his old rule of never painting the dead, and did several works based on photographs of Dyer. Dyer’s suicide was eerily familiar to Bacon, occurring in Paris on the eve of Bacon’s 1971 retrospective at the Grand Palais. In 1962, on the opening day of Bacon’s first retrospective (at the Tate), the artist learned of his lover Peter Lacey’s death in Tangier. Bond’s notes inform us that in both cases Bacon went on with the show, maintaining his poise even to the point of being charming with journalists and the public. But such a performance makes sense under Bacon’s rule of strictly compartmentalizing his work and his private life.

Francis Bacon: Five Decades also includes an essay by Ernst van Alphen that offers a helpful survey of critics’ responses to Bacon, including a discussion of Gilles Deleuze’s well-regarded analysis, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, which appeared in 1981. “Sensation” is a concept central to Bacon’s own assessment of his project—he stressed the physicality of his canvases. Many of them have deliberately paint-free spots where bare canvas is exposed. Bacon said in interviews that he aimed for the “nervous system” of his viewers and wanted them to apprehend, in a direct and unmediated way, the absolute reality of the human form. In this respect, he stood outside both the mimetic and abstract schools of painting, carving out a territory all his own. When he died of a heart attack at 81 while visiting a friend in Spain, an unfinished painting was waiting in his cluttered studio.

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.