Ask an LGTBQ+ author about their inspiration to write their first piece of fiction, and the answer may not be a book, but perhaps a play or a film. In my case, it was seeing the 1963 musical Oliver! on Broadway, which I saw when I was almost thirteen; I fell for Georgia Brown, who played Nancy. After wearing out two records of the soundtrack, I was hungry to immerse myself further into the story, so I read Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. This inspired me to set pen to paper and to begin my own novel, entitled Nancy, which I finished late that year.

Did I understand why I was so attracted to Georgia Brown and what it meant?

After finishing Nancy in 1963, I continued to write poetry and stories through high school, but I also secretly wrote some F/F (‘female/female’) short fiction, which I shared with one friend, both of us in a panic about being discovered for what we were reading (we weren’t). Many of my “straight” stories received awards and publication in my school’s literary journal, but then, when selecting universities, I chickened out and didn’t accept either Bennington or Bard Colleges to study creative writing, choosing instead to pursue a “safer” major — graphic design — at Carnegie Mellon University. Thinking back now, I wonder if this was safer because the writing was too close to my heart and too close to my undisclosed lesbianism.

After graduation, I worked for many years at university presses as a book designer, but it wasn’t until 2001 that my professional writing career began, with the acceptance of a poem in a literary magazine. This was followed by the publication of numerous short stories and poems, and my first poetry volume in 2009: Snow, Shadows, a Stranger. In retrospect, the title was revealing because I felt like a stranger in the shadows. Then, in 2012, my first novel, Jenny Kid, was published. Set in Venice, the female protagonist, Jenny Kidd, is a young artist who is uncertain about her sexual orientation. At a masquerade, she is dazzled by a seductive countess and becomes entrapped in a plot reminiscent of those by Patricia Highsmith. Thinking back, I wonder: if my own ambivalence about writing a lesbian character channeled into Jenny’s confusion. Did I supply an excuse for Jenny to react to this elegant, glamorous noblewoman because anyone—male or female—would be attracted to her?

With thirteen novels and four poetry collections under my belt, I now realize the delay in my career may have been subconsciously related to my fear of being outed,

and the fear of my parents reading work that was gay— especially the love scenes. This is somewhat odd because I was open about my lesbianism at age twenty-five, yet, I think it was coincidental that my first books were published after my parents died. I wonder how many LGTBQ+ writers postponed their work until their parents were gone. Perhaps writing about queer characters produces more anxiety because the creative process is uniquely intimate. And for some of us writers — of a particular age—we may still feel the faint shadow of the anti-LGBTQ rhetoric that hung over us during our formative years. Regardless of how open we are now about our relationships and who we love, it’s difficult to erase this haunting disquiet, but we strive to march forward and try not to let it deter us from writing the fiction we wish to write.

Although nine of my books showcase gay characters, three of my novels and many of my short stories feature heterosexual characters and plots. Writing the latter seems to engender a sense of balance or maybe it might be more truthfully described as subconscious relief. And even in the fiction with protagonists who are LGTBQ+, they are set in the real world, i.e. amid a predominantly heterosexual population. In this regard, I differ from many lesbian authors who create environments almost exclusively peopled by and written for lesbians. While these titles have great value for this audience, I’ve espoused a mentality similar to that of Gore Vidal, whose work I’ve always admired: I don’t consider myself an LGTBQ+ writer; I am simply a writer who sometimes creates stories that include LGTBQ+ characters, though they are treated as an integral part of the social fabric and don’t exist in a world unto themselves.

I appreciate and even envy the freedoms younger writers have experienced because LGBTQ writing empowers their openness, sense of community, and social inclusiveness. However, my writing was shaped during a different time and, as a result, I am a more interior, solitary novelist. My experience growing up in the fifties and sixties, during a very closeted time in America, with parents who were emotionally reserved, has definitely affected my life and my writing, making it more restrained. My characters tend to be creative loners, many of whom place their work above forming relationships; some are in the process of deciding their orientation or are teenagers, such as in my coming-of-age novels; some are undecided or ambivalent, though leaning toward a future with same-sex partners.

In addition to not writing for a specific readership, I also span genres, ranging from psychological suspense, comedy, young adult, and literary. Perhaps the best descriptor is that I’m a “bridge writer,” who writes the book that comes to me, the story and characters who capture my attention, with plots that unfold organically. Although I sometimes have a notion of how a novel will end, most often I give my characters free reign to see how they will behave in whatever kinds of situations they may encounter. This includes female protagonists who will be attracted to other women, male characters who will be attracted to other men, or straight narrators who follow a heterosexual path. Although this flexible approach feels the most natural, it can be a challenge when many readers, like their authors, stick to a specific genre and consistently feature either queer or straight primary characters.

For my most recent published work, The Black Leapord’s Kiss & The Writer Remembers, I decided to take a chance and create two linked novellas that feature magical realism and Orlando-esque touches, with the protagonist rocketing between childhood and late adulthood. The book allowed me to synthesize many present-day thoughts and concerns while also plunging into how it feels to be both a child and a teenager who was dealing with a powerful need to write and wrestling with attractions to other girls, while also incorporating fictional situations to enhance the plot. The work is risky in that it doesn’t follow the structure of my previous fiction and ‘flies high’ in a literary sense, yet what fun this book was to write and what an exhilarating feeling of freedom to toss the usual stylistic structures into the air! And how liberating to write about an author who shares some of my traits, who struggles with some of the same identities and emotions: partial disability, age, personal reticence, and the dim echoes of disapproval from decades prior!

Like the girl who repeatedly listened to Oliver! and wrote secret stories behind closed doors, I’m still a private person and writer, but by creating characters who take risks and explore, and are often braver than myself, I’ve been able to expand my own experience, which is, after all why readers read and why this writer writes.

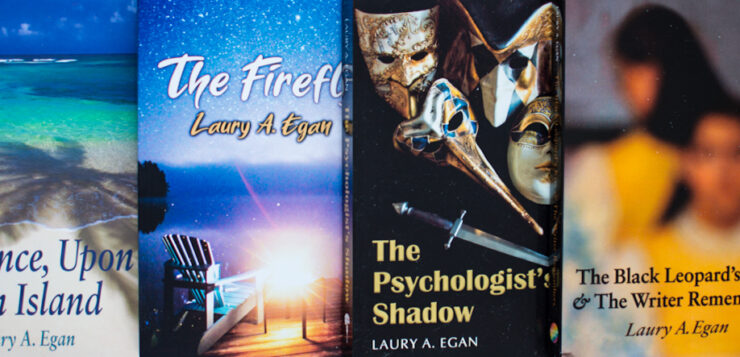

Laury A. Egan is the author of thirteen novels, including The Black Leopard’s Kiss & The Writer Remembers; The Psychologist’s Shadow; Once, Upon an Island; and The Firefly; t collection, Fog and Other Stories; and four volumes of poetry. Her short fiction and poetry has been published in 85 literary magazines and anthologies. You can read more of her work on her website.

Laury A. Egan is the author of thirteen novels, including The Black Leopard’s Kiss & The Writer Remembers; The Psychologist’s Shadow; Once, Upon an Island; and The Firefly; t collection, Fog and Other Stories; and four volumes of poetry. Her short fiction and poetry has been published in 85 literary magazines and anthologies. You can read more of her work on her website.

Discussion1 Comment

Thank you for posting my essay about my beginning as a writer! Very kind!