Published in: May-June 2014 issue.

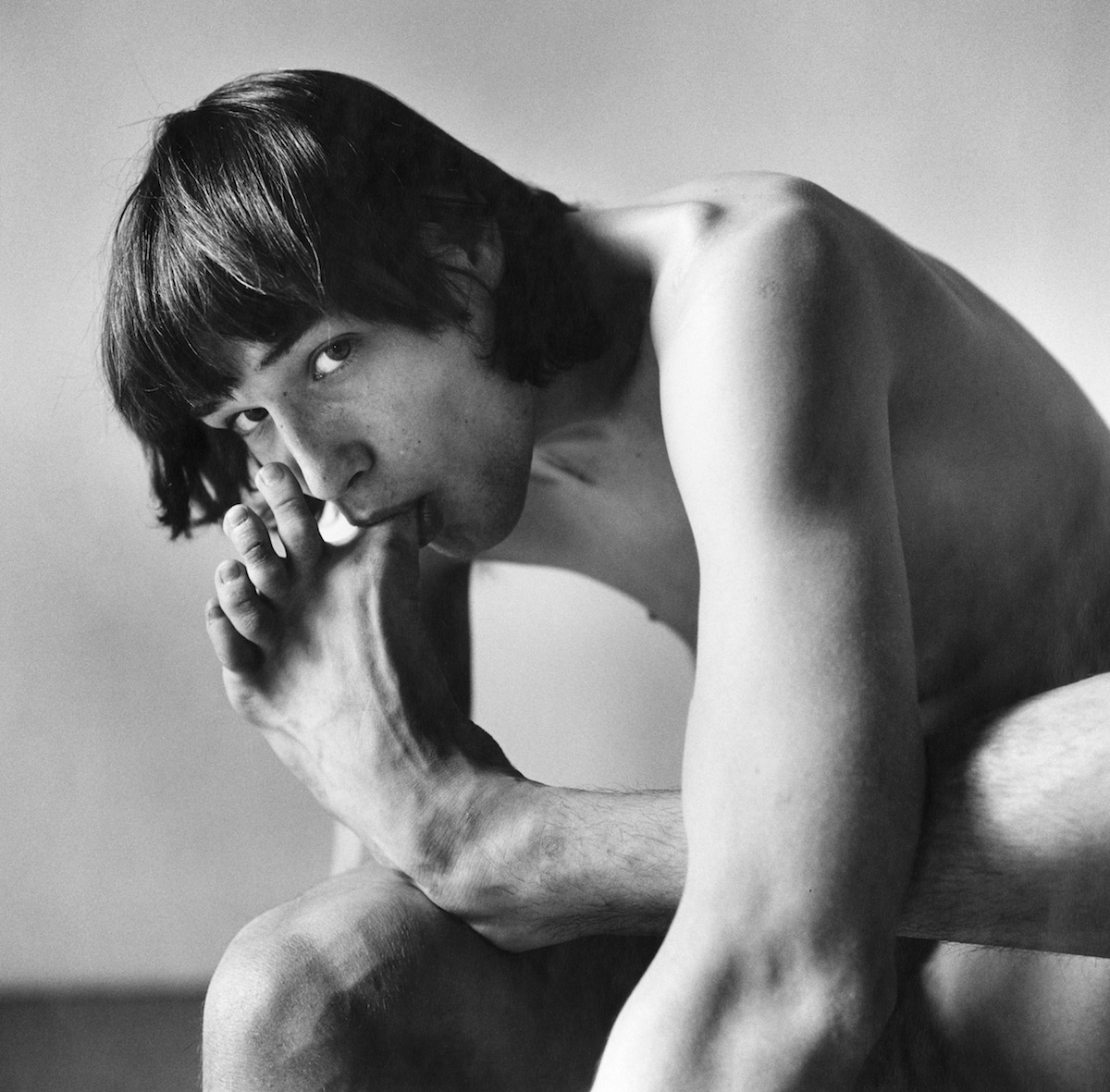

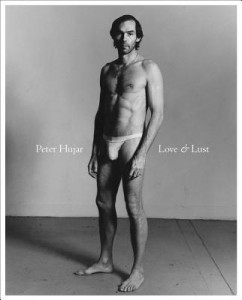

Peter Hujar: Love & Lust

Peter Hujar: Love & Lust

Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Jan. 4–March 8, 2014

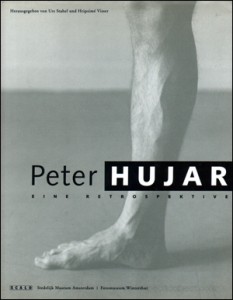

Exhibit Catalogue

Exhibit Catalogue

Fraenkel Gallery. 82 pages

with 36 tritone illustrations, $45.

PETER HUJAR (1934–1987) began as commercial photographer’s assistant, then shifted to the world of fashion before turning exclusively to fine art photography. This trajectory is identical to that of his mentor, Lisette Model, who also taught many other fashion-to-fine art photographers, notably Richard Avedon, David Bailey, Annie Leibovitz, Helmut Newton, and Irving Penn.