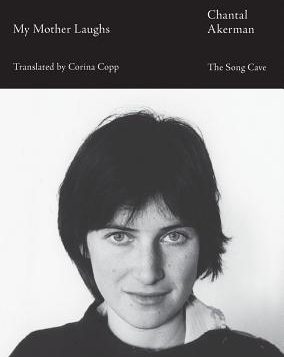

My Mother Laughs

My Mother Laughs

by Chantal Akerman

Translated by Corina Copp

The Song Cave. 173 pages. $20.

CHANTAL AKERMAN’S memoir My Mother Laughs is similar to her films: layered, defying time and space, concerned with the quotidian. Her work is woman-centered, often lesbian-centered, and focused on describing the position of women in society, including how the oppressive forces of patriarchy inflict both physical and emotional trauma on women. This memoir chronicles her experience of witnessing her mother’s death. The life of her mother Natalia (Nelly), a Holocaust survivor, is a theme that runs through much of Akerman’s works. It was an intense but anguished relationship.

The memoir focuses on the often banal daily activities of the two women’s lives. The writing is diaristic and fragmented, moving from Akerman’s interior world to the pedestrian events of her day. We get glimpses of her life, which is split among teaching at City College in New York, breaking up with her lesbian partner, and phoning and visiting her mother in Brussels. She homes in on Nelly’s physical deterioration: her mother’s broken shoulder that would not heal. The theme of wounds that are beyond repair underpins the love–hate relationship that Akerman has with her mother. There are unresolved tensions between mother and daughter involving the latter’s lesbianism and her Jewish identity. Shadowing my reading of this memoir was my awareness of Akerman’s suicide in October 2015, a year after the death of her mother. It occurred just days before the release of her final film, No Home Movie, which serves as a companion work to her memoir. The film gives us a portrait of her mother at the end of her life—a life of unimaginable and unspoken trauma as an Auschwitz survivor. Akerman was a filmmaker of extraordinary individuality, refusing to label herself. She did not want her films to be shown exclusively at feminist, LGBT, or Jewish film festivals, which would box them into politically correct ghettos. She also wanted to reach general mainstream audiences—to “woke” them from their habitual ways of seeing. Two of Akerman’s films seem to me to stand out as masterpieces: Je Tu Il Elle (1976) and Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, Bruxelles 1080 (1975). Both deal with female sexuality in ways not seen before in film. Je Tu Il Elle has a lesbian sex scene that’s nearly seven minutes long. Both graphic and loving, the scene is representative of a feminist gaze that upends patriarchal objectification of women. Similarly, Jeanne Dielman chronicles the trance-inducing banality of women’s domestic lives while simultaneously smashing long-held taboos on female sexuality and violence. There is no simple explanation for Akerman’s creative work, and likewise there is no simple answer to her death by suicide. Her memoir offers a window into a creative though troubled interior world in all its complexity. In the pantheon of auteur filmmakers, she was a radical pioneer of feminist, lesbian, and Jewish cinema.

Irene Javors is a frequent contributor to The G&LR.