THE LETTERS OF THOM GUNN

THE LETTERS OF THOM GUNN

Edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler, and Clive Wilmer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

800 pages, $45.

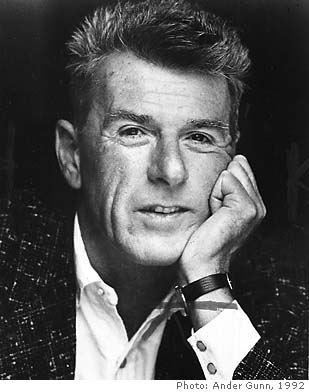

THOM GUNN (1929–2004), though widely recognized as a major British poet of the later 20th century, has often been marginalized by a literary establishment that has never been able to deal fully with his evocative, and explicitly gay, poetry. The publication of Gunn’s letters represents the start of what the poet Andrew McMillan has called “a welcome rebalancing.” As well as providing an intimate portrait of Gunn, the letters also give an insight into the origins of this imbalance. An unmistakable thread running through his letters is the extent to which he was forced to negotiate with a hostile culture as a poet who was a gay man.

Some of the most touching moments are found in Gunn’s love letters to his life partner, Mike Kitay, whom he met at Cambridge in 1952 and followed to the U.S. when he returned home two years later. These letters serve as an important record of how gay men constructed relationships in the pre-Stonewall era: “I love you wholly, so much with all of myself, that I don’t know what to do or say when there are other people by.” Yet between these tender moments are glimpses of the difficulties they both faced. In an early letter to his mentor Yvor Winters, Gunn is forced to invent an imaginary fiancée, as Winters “would have been appalled at the idea I was queer.” More worryingly, in 1956, when Mike was completing two years of compulsory service in the Air Force, Gunn writes in a panic to a friend: “Mike is being ‘investigated’ for homosexuality.” He recounts how they were outed by another man who had “seen us in some queer bars around here,” and how their apartment had been searched by the military police. Mike was threatened with a court-martial, and in the letter Gunn asks—in near desperation—that a female friend from Cambridge pretend to have been Mike’s girlfriend in order to throw off the investigation.

The letters reveal how Gunn’s development as a poet was shaped by his need to censor himself. He didn’t come out publicly until 1975, but as early as 1961, in a letter to Kitay, he expresses his “strong desire to write openly queer poems.” Nonetheless, he has to qualify that these are “not for publication—or else for publication under a pseudonym.” Evidence from Gunn’s archives shows that he wrote a number of “openly queer poems” throughout the ’60s and early ’70s, but had to edit out their gay content, delay their publication, or leave them unpublished. One such poem is “Nice Thing,” a candidly gay and erotic work, which Gunn hoped to include in his 1971 collection Moly. However, enclosing the poem in a letter, he acknowledges that he would be “quite surprised if Faber consents to print it.” Referring to his editor at Faber, Charles Monteith, he writes: “I can just picture poor Uncle Charles trying to write the letter in which he tells me that though he thinks it’s all right the others don’t want to print it.” (The poem eventually made it into print in 1982.)

Gunn’s difficulties with the literary establishment did not end once he began to publish openly. In a 1981 letter, he complains to the editor of a well-known poetry magazine about what he perceives as its “antigay stance” (it had published an article defending the use of the terms “fag” and “faggotry’). Similarly, Gunn was clearly hurt by the “bitchy” attitude of English reviewers to his 1982 collection The Passages of Joy, which was “dismissed so contemptuously by Peter Porter and Ian Hamilton and all the other powers.” By today’s standards, the tone of these reviews seems decidedly homophobic. Hamilton wrote that Gunn’s poems dealing with queer experience “simply make one want to look the other way,” while as distinguished a critic as Terry Eagleton stated that the collection “has little to recount beyond casual encounters and homosexual gossip.”

Gunn had far more to offer than “homosexual gossip.” The 1980s would prove to be the most difficult decade of his life, as he bore witness to the AIDS crisis sweeping through San Francisco. But it was also the decade in which he produced his finest work. Even while caring for friends who were dying of AIDS, he was writing the powerful, unsparing elegies that would become his most famous collection, The Man with Night Sweats. Once again, the letters prove an invaluable record, shedding light on the extraordinary lived experience behind Gunn’s poems. For instance, he recalls nursing Jim Lay, a member of his “queer household” who died in their home on Christmas Day, 1986: “Poor Jim, who shrank and shrank till he was about three stone, all bone, poor baby, couldn’t eat and the last three days couldn’t even swallow liquids. We squeezed wet sponges on the roof of his mouth to moisten it.” The opening lines of Gunn’s elegy for Lay, “Words for Some Ash,” recall the same details: “Poor parched man, we had to squeeze/ Dental sponge against your teeth,/ So that moisture by degrees/ Dribbled to the mouth beneath.”

Beyond his specific concerns as a gay man, Gunn’s letters illuminate the rich and varied life that informed his poems: his struggle to come to terms with his mother’s suicide; his life-changing experiences with LSD in the 1960s; domestic pursuits like cooking and gardening in touching letters to his family in England. He often described himself as an “impersonal” poet, and this book offsets this tendency with profound insight into his life and work. The editors provide a timeline of significant life events, a glossary of names, and detailed yet unobtrusive annotations of the letters. The collection opens with a letter Gunn sent to his father as a ten-year-old and closes with one to his brother from February 2004, just two months before his death.

In this final letter, he reports on the fact that the new mayor of San Francisco “decided as his first act to authorize the issuance of marriage licenses to people of the same sex, and so far there have been about 3000 gay marriages.” Such moments remind us how Gunn’s life ran parallel to the struggle for gay rights. Even as this collection deepens our understanding of his work, it reminds us of how his writing was affected by anti-gay attitudes. For much of his career, he was simply unable to publish openly—a fact that makes this encounter with his private voice all the more valuable.

Felix Hawlin is a doctoral candidate at Durham University with a specialty in Gunn’s poetry.