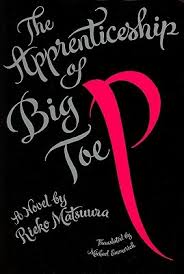

The Apprenticeship of Big Toe P

The Apprenticeship of Big Toe P

by Rieko Matsuura

Translated by Michael Emmerich

Kodansha International

447 pages, $24.95

OVER THE PAST fifty years or so, Japanese literature has had a distinctive strain of what could be called magical realism. Many of its novels feature characters who undergo startling personal transformations manifested by uncommon, or downright bizarre, changes in their living situation or personal appearance. The work of novelist Kobo Abe, widely available in English translation, is perhaps the best example of this. In novels such as The Face of Another (1964), The Box Man (1973), and Kangaroo Notebook (1991), as well as a play titled The Man Who Turned Into a Stick (1967), Abe explores characters who experience physical dislocation, deformity, and even cross-species metamorphosis. Abe uses these for his exploration of the diffuse nature of identity.

The work of another novelist, Rieko Matsuura, who is less well known to English readers, fits squarely within this category of Japanese fiction. Her 1993 novel, The Apprenticeship of Big Toe P, tells the story of a young woman, Mano Kazumi, who wakes up one morning to discover that the big toe of her right foot has transformed into a penis.

Matsurra’s novel is available for the first time to English readers thanks to Michael Emmerich’s translation. When the novel appeared in 1993, it made quite a splash, achieving critical and commercial success. The book’s subject probably had a lot to do with its sales. A more cynical critic might label the book pornographic, as not only does Matsuura lavish great detail on the sexual activity she describes, she also manages to invent sexual pairings, positions, and fetishes that border on the fantastic.

Other observers have written widely about the extremes of Japanese popular culture and the nation’s fascination with depictions of extreme violence and sexuality. (Japanese cinema provides many examples.) It has become a cliché of sorts to explain away these preoccupations by pointing to Japan’s traditionally “repressive” and highly mannered culture. Much has been made, too, of Japan’s ethic homogeneity, as well as its geography; these features might also be responsible for the recurring theme of physical transformation in Japanese literature and cinema.

It’s clear early on in Matsuura’s novel that she’s not out to exploit her theme for salacious purposes, even though the story’s graphic nature no doubt helped it gain word-of-mouth appeal. But Matsuura does seem to embrace the polemical. Kazumi’s transformation becomes an opportunity for her to explore, and question, not only her own sexuality but that of her many partners, and, by extension, it allows the novelist to comment upon Japanese society’s sexual mores. Matsuura makes sure this is not lost on the reader by including herself as a character (the female novelist “M”) in the novel’s prologue and epilogue. What happens within this frame is nothing less than a grand sexual adventure in which Kazumi achieves her transformative sexual and emotional education.

Kazumi is young, and while not sexually innocent before her transformation, she is rather naïve and emotionally undeveloped. As one can imagine, the sudden appearance of her new penis is not only bewildering; it’s also a source of fear and shame. Her new body part eventually prompts a split between her and her boyfriend, Masao, though not in a way one might expect. Masao actually accepts the penis, and though he keeps his distance from it, he jokingly refers to it as “little brother.” It’s Kazumi who changes most, losing interest in sex with Masao.

Soon after her breakup, Kazumi meets another young man, a blind musician named Shunji, who is boyish compared to Masao’s more masculine persona, and who possesses an alluring combination of innocence and sexual precociousness. He is equally comfortable in bed with both men and women. But he’s also emotionally unaffected by sex, using it solely as recreation. Shunji becomes a liberator for Kazumi, unleashing her into a new world of sexual awareness and exploration after he unhesitatingly fellates her toe penis. In falling in with Shunji, Kazumi becomes entangled in his sordid circle of friends and lovers, for there are many around him who are more than willing to take advantage of his easygoing manner, and his naïveté.

Kazumi and Shunji meet and join a troupe of underground performers, The Flower Show, who offer secret, live sex shows that feature their diverse sexual abnormalities. The troupe includes, among others, a transsexual; a young man with a uniquely shaped penis; another young man who can only have sex via a Siamese-like twin; and an older woman who personifies the vagina dentata myth. For obvious reasons, Kazumi finds a sort of family among these people, and at their hands, through entanglements of one kind or another with each of them, she achieves enlightenment and “grows up.”

The Apprenticeship of Big Toe P is a long novel full of plot turns, extensive and varied sexual encounters, and long passages in which Kazumi and other characters meditate on the nature of friendship, sexuality, gender identity, and related themes. At times the novel seems too long, and the prose can become almost stridently political. Yet Matsuura takes her very strange cast of characters and makes them not only interesting, but even engaging and worthy of following on their strange journey.

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to the G&LR.