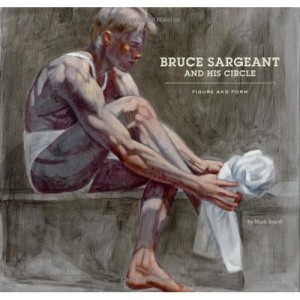

Bruce Sargeant and His Circle: Figure and Form

Bruce Sargeant and His Circle: Figure and Form

by Mark Beard

Chronicle Books. 144 pages, $45.

EVEN those who consider themselves well informed about 20th-century art have probably never heard of Bruce Sargeant (1898-1938). A sculptor, draftsman, and painter (not to mention a sometime poet), Sar-geant’s beaux arts training comes through in works that are focused almost exclusively on beautiful young men. While Sargeant’s art has long been prized by elite collectors in Europe and the U.S., it has never been featured in any major exhibition or survey. Mark Beard, an artist and distant relative of Sargeant, has devoted twenty years to collecting and studying the neglected artist’s work. The result of this effort, Bruce Sargeant and His Circle goes a long way toward rectifying this state of neglect.

The beautifully printed volume features many full-color plates of a wide array of Sargeant’s paintings, drawings, and sculptures. (And while it favors the life studies, it does include a few examples of Sargeant’s still lifes.) Beard also provides a helpful biographical introduction and a timeline of Sargeant’s short but eventful life. In addition, Beard offers compact sections featuring the work of other artists: Sargeant’s teacher, Hippolyte Alexandre Michallon; two of his friends and contemporaries, Edith Thayer Cromwell and Brechtholdt Streeruwitz; and the contemporary painter Peter Coulter, who was a student of both Cromwell and Streeruwitz.

So who was Bruce Sargeant? He was born in England to an American mother and British father. The latter’s successful business ventures allowed the family to live well and travel often. Although Sargeant’s father wanted Bruce to take an interest (and no doubt eventually run) the family businesses, the young man had interests of his own, and was apparently keen on realizing them. These included poetry, painting, travel—and other young men.

During a 1916 visit to New York City, Sargeant saw the work of “Ashcan school” painters John Sloan, George Luks, and others, and that encounter sparked an interest in art. Rejected from military service for medical reasons, Sargeant returned to England and worked in the ambulance training corps during World War I, but saw no military action. He eventually studied art at London’s Slade School (under the instruction of the École des Beaux-Arts-educated Michallon), and began to paint commissions. In addition, he spent time with the famed Bloomsbury group and continued to write poetry.

In 1924, his affair with a boy in his hometown of Rotherham caused a minor scandal, and Sargeant’s father forced him to move to Winnipeg, Canada, where he carried on a correspondence with his lover and pined for home. With the death of his father in 1926, Sargeant was able to return to England. While his romance with his young lover soon faded, his newfound freedom, and the money he got from the sale of his family’s businesses, allowed him to continue his travels, his painting, and his love affairs (including, during a 1936 stay in Berlin, an affair with a Nazi youth). In 1938, during a wrestling match with a younger man, the forty-year old Sargeant was killed when his neck broke as a result of a powerful scissor-lock.

As Thomas Sokolowski, director of the Andy Warhol Museum, notes in his foreword to Beard’s book, the beautiful young men in Sargeant’s paintings seem to exist in an idealized, timeless world “terribly removed from our own.” They are rowers, wrestlers, boxers, gymnasts, and also soldiers. Their bodies are perfectly muscled and proportioned, their faces uniformly chiseled and handsome, their hair thick, wavy, and usually blonde. These are pictures that are very much a product of their time, the era of interwar England, the world of E. M. Forster and Evelyn Waugh. Sargeant’s subjects embody the 5th-century Athenian ideal of male beauty, young men who have earned the right to be admired as much for their athletic prowess as for their physical perfection.

Removed as it is from our world, Sargeant’s paradise of gorgeous lads nevertheless looks strangely familiar. One is reminded of the American painter, Thomas Eakins—indeed, an early observer dubbed Sargeant “the English Eakins”—and of later artists such as Paul Cadmus. Recent critics have remarked upon the debt that photographers like Herb Ritts and Bruce Weber owe to Sargeant. It’s no surprise, then, that Abercrombie & Fitch recently featured installations of Sargeant’s works in some of its stores. Sargeant’s young men exemplify the same notion of carefree, youthful beauty, and homoerotic energy that have become the clothing retailer’s trademark.

Beard’s book does a great service by focusing new attention on Sargeant and identifying the influence he continues to have. But the brief biographical information included in the book seems to prompt as many questions as it answers. For example, Sargeant resided briefly in Berlin, had a Nazi lover, and painted flattering portraits of German Olympic athletes, facts that might prompt one to wonder if he harbored Nazi sympathies. Beard does not explore this in his introduction or elsewhere in the book. Sargeant’s contemporary, Streeruwitz, was quite proud to have one of his works included in Hitler’s famous exhibit of “degenerate” art, and one hopes that Sargeant would have stood firm with his friends who stood against the dictator. That said, Bruce Sargeant and His Circle is a handsome and welcome testament to the work of a largely forgotten artist.