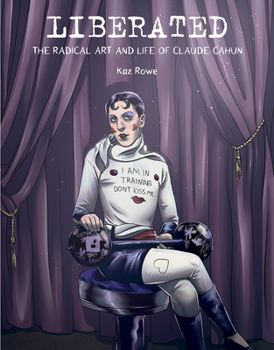

LIBERATED

LIBERATED

The Radical Art and Life of Claude Cahun

by Kaz Rowe

J. Paul Getty Trust. 96 pages, $19.95

CLAUDE CAHUN was an essayist, a novelist, a pamphleteer, a sculptor, an artist, a monologist, an actor, and a photographer during the early 20th-century Surrealist movement in France. In collaboration with Marcel Moore, Cahun created photographic self-portraits and hosted a salon with regular attendees that included André Breton and Sylvia Beach. Cahun and Moore were very active in the French Resistance against Hitler and the Nazis. They were lovers from the time they met in 1909 until Cahun’s death in 1954.

Born Lucy Renée Mathilde Schwob in 1894, Cahun might have preferred the term “non-binary” over “lesbian” if she were alive today. In her 1930 memoir Disavowals, she wrote: “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Marcel Moore (née Suzanne Alberte Malherbe), it appears, was similarly noncommittal on the matter of gender.

That “neuter” quotation is one of many that occur throughout Kaz Rowe’s new graphic biography of Cahun, Liberated: The Radical Art and Life of Claude Cahun. Rowe, a cartoonist, illustrator, and YouTube influencer, is a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago. They completed their BFA in 2018 with a brief comic biography of illustrator J. C. Leyendecker titled “He Lives in the Echoes.” While working on Liberated, Rowe turned to YouTube, where they create educational videos about underrepresented queer histories. Rowe was drawn to Cahun and Moore’s “breathtaking life story” and produced a loving homage of graphic nonfiction to honor them.

Born in 1894, in Nantes, France, Lucy Schwob was raised by her grandmother from 1897 to 1905. Her grandmother taught her about their Jewish heritage and exposed her to the literary classics. In 1908, Lucy went to the Parsons Mead School in Surrey, England, to ensure her safety amid the anti-Semitism in France that had been stirred up by the Dreyfus Affair. (One day in school, she was tied to a tree with a skipping rope and stoned by anti-Semitic students.)

Born in 1894, in Nantes, France, Lucy Schwob was raised by her grandmother from 1897 to 1905. Her grandmother taught her about their Jewish heritage and exposed her to the literary classics. In 1908, Lucy went to the Parsons Mead School in Surrey, England, to ensure her safety amid the anti-Semitism in France that had been stirred up by the Dreyfus Affair. (One day in school, she was tied to a tree with a skipping rope and stoned by anti-Semitic students.)

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.