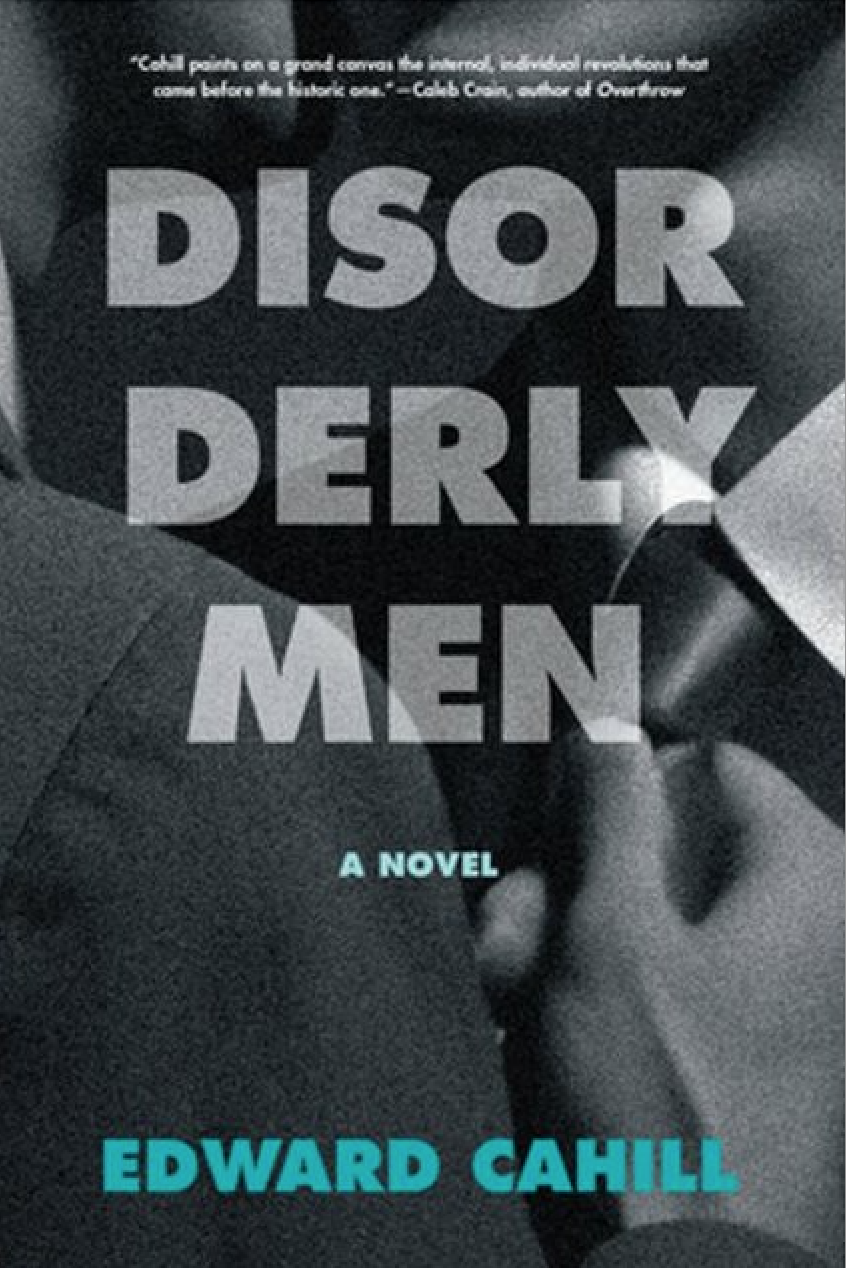

DISORDERLY MEN

DISORDERLY MEN

by Edward Cahill

Fordham Univ. Press. 342 pages, $28.95

SOMETIMES our pre-Stonewall history can feel downright prehistoric. Few of us lived through Senator McCarthy’s red-baiting and the “lavender scare,” when LGBT people were purged from jobs in the federal government. Some of us do, however, remember times when our bars and clubs were routinely subjected to police raids, which continued into the late 1970s. Patrons could be roughed up by rogue cops, arrested, fingerprinted, and photographed like criminals. Worse, their names, ages, addresses, and places of employment were published in newspaper accounts of the raids, causing them to lose their jobs, their family ties, their homes, and sometimes their very lives. Such raids were commonplace in American cities in the 1960s, including in New York, where things came to a head at the Stonewall Inn in 1969.

Edward Cahill’s novel Disorderly Men begins with just such a police raid on the fictional Caesar’s bar in New York’s Greenwich Village in the early 1960s.

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.