THIS IS THE SECOND PART of my interview with Edmund White, in which he discusses two books that have recently been released: Jack Holmes and His Friend, a novel; and Sacred Monsters, a collection of more than twenty of his essays and reviews on artists and authors. In the first part, he talked about amour fou (“crazy love”), Paul Bowles, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and Susan Sontag. Here, White discusses other “sacred monsters,” a term derived from the French, which describes “a venerable or popular celebrity so well known that he or she is above criticism, a legend who despite eccentricities or faults cannot be measured by ordinary standards.”

Of the authors and artists discussed in Sacred Monsters, White explains: “Fifteen of my subjects were gay or bisexual or closeted or conflicted about their sexuality. Glenway Wescott, for instance, lived openly with his partner Monroe Wheeler and with their erstwhile third wheel, the photographer George Platt Lynes, but they were all three in the public eye and had to practice a measure of discretion, especially during the witch-hunting McCarthy years. Wheeler directed publications for the Museum of Modern Art, Wescott was for a long time the president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and Lynes was one of the most celebrated American photographers.” White also continues his discussion of his latest novel, Jack Holmes and His Friend, which represents a departure from his notably cerebral fiction and edges toward a more narrative prose style, one less discursive and æsthetic.

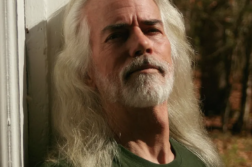

Edmund White spoke with me last November from his home in the Chelsea section of New York City.

— Michael Ehrhardt