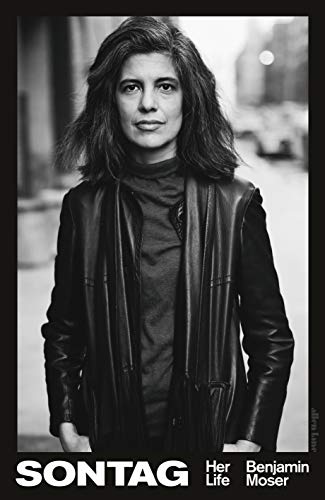

Sontag: Her Life and Work

Sontag: Her Life and Work

by Benjamin Moser

Ecco. 832 pages, $39.99

BENJAMIN MOSER’S biography Sontag: Her Life and Work makes a show of presenting Susan Sontag’s life in a nonjudgmental way, but I fear he is not always successful in this undertaking. Although the book is a virtual kitchen sink of information about Sontag’s life, Moser seems to have started the project with certain expectations about Sontag that she does not live up to in his estimation.

He begins with a wealth of details about her early life—notably the death of her father, her alcoholic, fault-finding mother, her terrible marriage to Philip Rieff, the birth of their son—and moves on to her vast array of lovers, both male and female, and to her lifelong inability to come to terms with her sexuality, which was undoubtedly lesbian at root. We learn of her relentless ambition to be famous and to be taken seriously as an essayist and a novelist.

At some point in this gargantuan biography, Moser takes a detour and decides to change the focus, moving in the direction of psycho-biography. Ironically enough, psychologizing was anathema to Sontag herself, who criticized writers who engage in this practice in her 1966 essay “Against Interpretation,” where she singled out writers who attempt to explain a person or character in terms of a single motive or characteristic rather than from multiple perspectives.

Sontag is presented as not only unhappy in love but also dissatisfied with herself in just about every aspect of her life. She wanted to be known as a novelist, yet fame came for her essays. She dreaded being alone, but she was often unapproachable. She hated to bathe and often didn’t change her clothes for days. She ate “weird” stuff, smoked incessantly, took speed to stay awake during her all-night writing marathons, and wasn’t the perfect mother.

In short, Sontag was a complex person; she was idiosyncratic; she did things differently. But Moser does not do an adequate job contextualizing her as a woman and an intellectual who was born in 1933 and came of age in the late 1940s and ’50s when a woman’s highest vocation was to get married and raise children. Sontag was a brilliant woman, a lesbian who wanted a life of the mind. She wanted to be known as a writer and an intellectual—not as a woman writer or lesbian writer or a Jewish writer. She felt that such adjectives lessened her work in the patriarchal literary and intellectual worlds. When she wrote about cancer in Illness as Metaphor (1978), she did not personalize the discussion by talking about her own cancer. She wanted to convey a universal message that wasn’t just about her.

Moser is the most damning of Sontag with respect to her insistent avoidance or denial of her sexual orientation. As the author of Notes on Camp (1964), she displayed an intimate knowledge of gay life that no heterosexual at this time is likely to have had. Later on, although her lesbian affairs were an open secret, she maintained a level of discretion that seemed unnecessarily defensive, especially as the years passed and more and more people came out of the closet. Moser especially takes her to task for not coming out during the plague years at the height of the AIDS pandemic. She wrote AIDS and Its Metaphors in 1988 but refrained from publicly revealing her lesbian identity. Moser reminds us of the disappointment and betrayal that many people felt at the time.

Moser moralizes about this denial rather than making any attempt to understand it. Whatever the psychological issues driving Sontag’s inner world, her lesbian self was an area in her life that she found it difficult to talk about. Sontag’s younger sister Judith recounts that Susan always referred to her lovers by using “he” rather than “she.” Her obituary in the Times did not name Annie Leibovitz as her partner. We are left with the fact that Sontag had the courage to go to Bosnia and dodge bullets and rockets, but when it came to leaving her lesbian closet, she found the world too dangerous to negotiate.

Moser’s book is a mixed bag of biography, psychology, and literary analysis. It did not have to be such a doorstop; indeed, it needed a good editor to cut some of the repetitious references. Moser’s journey as a biographer of Sontag is perhaps the more interesting story as he goes from adulation of an idealized Sontag to disappointment when he discovers her darker corners and vulnerabilities.

For those interested in reading Sontag’s own journals for a more authentic understanding of what she thought and felt, the following are suggested: Reborn (2008), journals from 1947-1963, and As Consciousness is Harnessed To Flesh (2012), journals from 1964 to 1980 (both of which were reviewed by me in these pages when they were published, in 2009 and 2012, respectively).