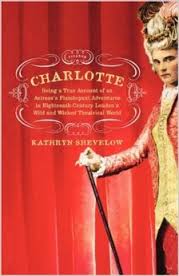

Charlotte: Being a True Account of an Actress’s Flamboyant Adventures in Eighteenth-Century London’s Wild and Wicked Theatrical World

Charlotte: Being a True Account of an Actress’s Flamboyant Adventures in Eighteenth-Century London’s Wild and Wicked Theatrical World

by Kathryn Shevelow

Henry Holt. 433 pages, $27.50

“I’M ALMOST THROUGH MY memoirs, and I’m here!” sings aging actress Carlotta Campion in the musical Follies, as she casts a rueful eye over decades of ups and downs. Her song, “I’m Still Here,” might almost have been inspired by Carlotta’s namesake of some two hundred years earlier, Charlotte Charke. Born in 1713 as the daughter of Colley Cibber—actor, playwright, libertine, and poet laureate, dubbed “King of the Dunces” by Alexander Pope in The Dunciad—Charlotte would follow her father into a theatrical career, one marked by early acclaim in comic roles.

Charlotte Charke’s eagerness for bigger parts led her to form her own “Mad Company,” but her penchant for playing male roles proved her undoing—especially when she took to wearing men’s clothes off stage, prompting paternal rejection and provoking the manager of the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane to fire her. Even though both men soon relented, Charlotte joined an upstart company led by the satirist Henry Fielding, who gave her full rein to wear breeches and to parody her father on stage. But Fielding’s audacious political farces, which lampooned the king and the prime minister, triggered a disastrous backlash. The Stage Licensing Act of 1737 had made it a criminal offense to stage plays anywhere in London outside of three authorized houses, which left Charlotte and many other actors scrambling for their livelihood.

For the next 23 years, Charlotte hurtled headlong through a dizzying series of attempts to support herself and her daughter Kitty (the child of her first husband, Richard Charke). “Oil merchant, sausage seller, innkeeper, pastry cook, gentleman’s valet, waiter, and puppeteer”—she tried all these occupations, and more, punctuating them with stage appearances. But bouts of illness and an inability to manage money continually frustrated her hopes for security. The specter of debtor’s prison loomed constantly, turning her transvestitism from a daring diversion into a necessary way of disguising herself from creditors. Even when she found work as an itinerant actress (usually with unlicensed companies), she lived precariously from week to week, troupe to troupe, dancing on the brink of—and sometimes slipping into—destitution. For Charlotte, constantly re-inventing herself was not some postmodern cliché; it was a dire necessity.

Charlotte’s most popular and enduring work was not her acting but her autobiography, issued in 1755. (It was also one of her most lucrative.) Today we’re so accustomed to tell-all memoirs as part of the machinery of celebrity that it may come as a surprise that the commercial publication of a personal memoir, still a new invention, was a rare occurrence in the 18th century. Hence Charlotte’s was “the first English autobiography written by an actress.” Like so much of her career, her Narrative was both an emulation of her father, who had published his own life in 1740, and a frustrated attempt to get his attention. Charlotte wrote openly about her frequent cross-dressing on and off stage, but her motives for it remained mysterious. Although it had become an expedient for evading creditors, it had originated in a “predilection” in her childhood. As Shevelow makes clear, Charlotte was only one of several women who became famous in the 18th century for passing as a man. But Charlotte took special delight in recounting her male adventures, which included turning down at least one proposal of marriage from a female admirer.

Charlotte herself had two husbands, having remarried briefly after Richard Charke’s death, but the only relationship that seems to have fully satisfied her was her companionship of many years with another actress. The two of them lived and toured as a married couple, Mr. and Mrs. Brown. Was Charlotte, then, a lesbian? Shevelow acknowledges the ambiguity of the evidence and the dangers of projecting our own concepts of sexual identity onto the 18th century. Yet she concludes that “Charlotte and Mrs. Brown occupy an important place in lesbian history as one of the few historically visible same-sex couples from 250 years ago, even if we cannot say for certain how closely the modern term ‘lesbian’ characterizes their experience.”

Shevelow’s book, the first full biography of Charlotte to be published, is carefully researched and informed by extensive knowledge of English social and cultural life of the period. Whether she writes about the dangers of childbirth, prison conditions, London street life, or the privations of working as a strolling player, she weaves in vivid details that add background and context to Charlotte’s story, but does so without obscuring the narrative. Her lively writing is full of humor and empathy for her subject, and she’s not afraid to enliven it further with fictional touches—for example, imagining a performance of Fielding’s Pasquin with Colley Cibber in the audience watching himself be lampooned. For the most part, Shevelow gives the reader sufficient clues that these scenes are her own embellishments, and such genre-bending devices seem appropriate for a book about someone like Charlotte Charke. Occasionally, though, the author’s imaginative reconstructions seem strained, as does her insistence that her subjects “must have” felt this or that in the circumstances: “Colley must have recognized” a childhood prank of Charlotte’s as a parody of him, “Charlotte must have had mixed feelings” about an action of her father’s (emphases added). Such tendentious notes, though, don’t detract from the overall care with which Shevelow distinguishes evidence from supposition, likelihood from possibility. The fine lines of such distinctions—like the lines in the period engravings that illustrate this book—interweave subtly to draw a fascinating portrait of an extraordinary woman and her times.

Stephen Kuehler, a research librarian in Cambridge, Mass., is pursuing a master’s degree in theatre history at Tufts University.