Published in: March-April 2005 issue.

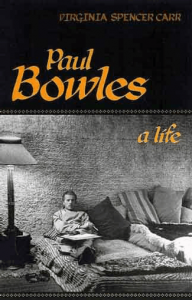

Paul Bowles: A Life

Paul Bowles: A Life

by Virginia Spencer Carr

Scribner. 409 pages, $35.

AMONG THE WRITERS whose names are associated with the Beat Generation—Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and the rest—perhaps only Paul Bowles is destined to transcend that association and secure his own place as an artist of the late 20th century. It’s appropriate to designate him as an “artist,” for Bowles was not only a critically acclaimed novelist, poet, memoirist, and translator; he also achieved fame as a composer of both classical and theatre music, and he was a photographer and illustrator, as well.