Published in: March-April 2005 issue.

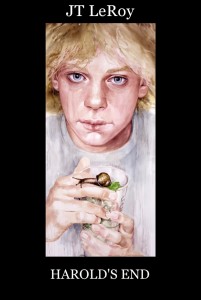

Harold’s End

Harold’s End

JT LeRoy

Last Gasp. 48 pages, $19.95

JT LeRoy’s new novella Harold’s End has the shape and feel of a personal diary or journal. Small in size and squarish in shape, the book sports a black cover (under the dust jacket) and, inside, the text is illustrated throughout with drawings of the story’s characters by Australian artist Cherry Hood. All of this makes perfect sense, because the story the narrator shares is the type of tale diaries are meant for: unabashedly intimate and filled with discoveries most of us would keep to ourselves.