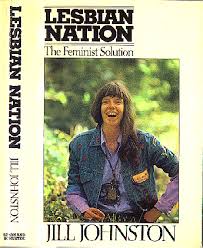

LESBIAN NATION was one of those books whose title said it all. The book itself was a series of essays published in The Village Voice from 1969 to 1972, written in the brash, brilliant, free-associating style for which Jill Johnston is famous—but it quickly became a “manifesto” for a segment of the population that was only beginning to come out in large numbers and get organized in 1973, just four years after Stonewall. The title became a rallying cry and a symbol of solidarity for those in the vanguard of this new movement and their followers.

The book’s subtitle, “The Feminist Solution,” referred to a dilemma of identity and political organizing that vexed many lesbians at the time: whether to honor their status as women by working with the burgeoning feminist movement, or whether to honor their lesbianism by joining the growing but increasingly male-dominated gay rights movement. Johnston’s solution was one that embodied both a stinging indictment of “the patriarchy” in all its manifestations and a stern critique of the straight feminist movement, which had witnessed periodic outbursts of anti-lesbian sentiment. The concept of a “lesbian nation” proposed a separation from both movements in favor of a radical brand of feminism in which men played almost no role—a feminism for women who needed only the company of other women. And not only out lesbians were invited to this party: “All women are lesbians except those who don’t know it,” Johnston famously wrote.

The book’s subtitle, “The Feminist Solution,” referred to a dilemma of identity and political organizing that vexed many lesbians at the time: whether to honor their status as women by working with the burgeoning feminist movement, or whether to honor their lesbianism by joining the growing but increasingly male-dominated gay rights movement. Johnston’s solution was one that embodied both a stinging indictment of “the patriarchy” in all its manifestations and a stern critique of the straight feminist movement, which had witnessed periodic outbursts of anti-lesbian sentiment. The concept of a “lesbian nation” proposed a separation from both movements in favor of a radical brand of feminism in which men played almost no role—a feminism for women who needed only the company of other women. And not only out lesbians were invited to this party: “All women are lesbians except those who don’t know it,” Johnston famously wrote.

Lesbian Nation qua “manifesto” has been credited with launching the lesbian separatist movement that produced, as the 70’s wore on, a bumper crop of women’s communes, coffeehouses, bookstores, and music festivals in the U.S. and Canada. Whether that was its intent is not entirely clear. With chapter titles like “The Second Sucks and the Feminine Mystake” and “Amazons and Archedykes,” Lesbian Nation was as much about wordplay and satire as it was about launching a separatist subculture. Indeed the often experimental writing was pitched at a high level of difficulty and complexity, hardly the stuff of political pamphleteering.

For all the historical importance of Lesbian Nation, the period of writing that produced it was in some ways a long detour for Johnston, who started life as a dance critic and resumed her career as an art critic in the 1990’s, turning especially to the visual arts with books such as Jasper Johns and Secret Lives in Art. In the interim, she produced a two-part autobiography (Mother Bound and Paper Daughter). A collection published in 1998, Admission Accomplished: The Lesbian Nation Years (1970–75), compiles Johnston’s essays during this five-year period and demonstrates in 56 pieces the breadth of her interests, which ranged from misogyny and same-sex marriage to language and literature. Her most recent book, At Sea on Land, published last year, is a meditation on travel and politics.

This interview was conducted by the Editor via the Internet in January 2006.

The Gay & Lesbian Review: This issue of the G&LR is focusing on some of the major turning points in the early rise of gay and lesbian culture. Your book, Lesbian Nation, was a landmark during this period (the early 1970’s) and became a manifesto for lesbian politics and organization. The book emerged out of a series of essays you wrote for The Village Voice. How did this series come about, and what role did the Voice play in these turbulent times?

Jill Johnston: Lesbian Nation, it’s true, emerged out of writings in The Village Voice—that would have been between 1969 and 1972. But these writings, which were technically columns, could only be said to have emerged from a prior ten-year involvement at the paper.

I began at the paper as a critic, in 1959, writing reviews and opinions about dance, art, happenings, Intermedia, the avant-garde generally, when the paper was just four years old. In the mid-60’s, an upheaval in my life turned me away from criticism to a running account of my adventures from week to week. These were daringly published by the Voice, even as my writing became more and more a-grammatical, disregarding all the textbook conventions. By 1968, this curious form was established, and was quite popular in the art world. In 1969, a few women in the GLF [Gay Liberation Front], finding me writing about my travels cross-country with a young woman, correctly divining that she was a lover, invited me to their meetings at a church on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan. And what followed became, as they say, history. Having been schooled in all the art forms, being very apolitical, I had a lot of resistance at first, especially to understanding the status of women in political terms. I had not a clue, in fact, that the genders were so seriously segregated, to the historical disadvantage of women. The fact that certain women, called lesbians, were outcasts, was not hard to get. So I started there.

The role, I would say, that the Voice played in “those turbulent times” as regarded my part in them was that it continued to publish me. It seems I became good copy. During the early 70’s they received hundreds of letters to the editor about my column. I received hundreds of them myself. And I never wrote about sex per se, by the way. It was just the L-word that did it. I can’t discount, however, the appeal of the craziness of my adventures—for example, encounters on the road on book tours with hostile crowds and raucous claques.

G&LR: Maybe you could talk a little about the historical and cultural backdrop out of which you developed your ideas about feminism and lesbian separatism. The antiwar movement and the counterculture were in full swing: what impact did they have?

JJ: Once I understood the feminist doctrines, a lesbian separatist position seemed the commonsensical position, especially since, conveniently, I was an L-person. Women wanted to remove their support from men, the “enemy” in a movement for reform, power, and self-determination. A revolutionary prototype existed in their midst. But the prejudice against women within the ranks of women, much less loving women at the intimate level, was so great (still is, of course) that feminists could only act against their own best interests and trash the women who modeled their beliefs. The split between straight feminists and lesbian feminists was extremely damaging, and will no doubt continue to be in any future wave, to the cause of women’s liberation. The internal damage within the lesbian feminist ranks was also lethal.

You ask about the backdrop of the antiwar movement and counterculture. The huge turmoil in the 1960’s produced an atmosphere of insurrection generally. That’s where we all came in. The media were making money off it, and book contracts were being handed out. The feminist movement was male-supported, -defined, and -perpetuated right down to the barricades. Lesbian Nation was bought by a male editor, titled by him, and produced and publicized by his male-owned corporation (Simon & Schuster). We were all agreeable, sometimes enthusiastic, employees. Money and exploitation aside, the men were information-gathering, finding out what we thought, what we were up to, how far we could go, and what concessions might be made by society and government before we were shut down.

G&LR: To what extent was the concept of a “lesbian nation” a literal concept, i.e. a vision of a world of women living lives independent of men? The ideas developed in Lesbian Nation helped to inspire the communitarian movement and separatist organizing of the 1970’s. Can you talk a little about some of these experiments and organizing efforts?

JJ: In a revolutionary time, separatism is inevitable. An oppressed group of people first must gather together to define themselves and seek mutual support. A “vision of a world of women living independently of men” was not a realistic, indeterminately future one. It was rather a stage in the process. Black separatism had the same profile. I see a number of stages like this (provided the earth survives) until the oppressor group ceases to exist as such. Straight women in the 70’s, of course, left their husbands and boyfriends in droves, many of them coming out, or trying to. Separatism was hardly carried out just by lesbians, all perceptions to the contrary. Merging was going on, and lines blurred. But at heart, the women’s liberation movement was one of reform, not revolution. Clamoring to get a better deal under patriarchy isn’t a bad way to define it.

G&LR: Lesbian Nation came at a time when both the women’s movement and the gay and lesbian rights movement were in their infancy. Lesbians had divided loyalties because of their dual minority status. Your book seemed to counsel women to move away from the world of men, including the male-dominated gay rights movement. Is this an accurate reading?

JJ: Yes, the women in the lesbian/feminist movement were defining themselves independently of men, including gay men. However, Lesbian Nation had the imprimatur of the mainstream mass media, which helped create consensus and identity. For example, copies of the book took up the entire window display of Brentano’s on Fifth Avenue.

G&LR: When Lesbian Nation was published, it quickly became a cultural event. How would you describe the reaction to the book in general? Why do you think the book had this kind of impact?

JJ: Gee, I can’t really answer your questions about the impact and results of Lesbian Nation. I was too much in the middle of it, and trying to survive its publication. As a writer, as which I chiefly identify myself, survival has been difficult to say the least.

G&LR: You obviously continued writing long after Lesbian Nation was published. How did your own thinking about feminism and GLBT rights issues evolve in the ensuing years? To what extent have you modified the central views you expressed in the book?

JJ: I haven’t modified anything I said in the book. I just don’t say it any more. As an evolving writer, however, the way it was written now looks weird to me. I’ve been through a number of stages of writing, subject- and style-wise, since then. Those several years naturally influenced my future writing, though it’s often hard to see how exactly, when the attitudes appear transformed in new subjects.

G&LR: How would you characterize the significance of the book in the larger context of the 1970’s and the GLBT rights movement? What would you say was the long-term impact of the book from a vantage point of thirty-plus years?

JJ: I have no idea about any significance of Lesbian Nation in the context of the GLBT rights movement. I personally am firmly lined up behind civil rights for gay men and lesbians. At the same time, I have otherwise always found the link between us to be weak to non-existent. Gay men, however discriminated against, are still patriarchs. My alignment was always with the women, across all lines. Personally, again and however, I had a number of male friends back then, and still do. I have a son Richard and a grandson Ben, among other male relatives and friends.