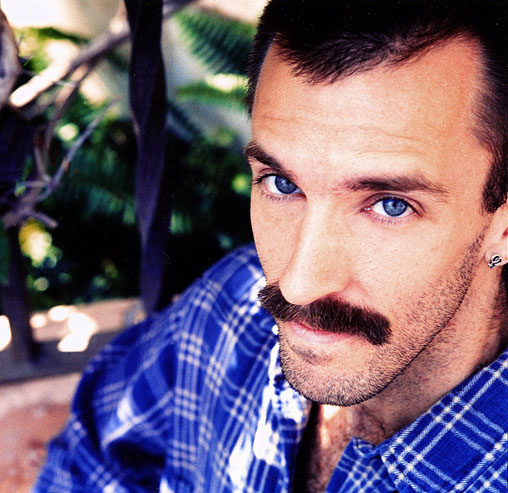

For a singer who describes his career as governed by “trial and error,” Mark Weigle has produced a steady output of CDs since his debut in 1998, and has attracted a loyal following across the U.S. That first CD was called The Truth Is, a title that promised to tell the truth about being a gay man living with HIV. His next two albums, All That Matters and Out of the Loop, added to his corpus of original songs, most of them ballads sung by Weigle with a band backing him up. He’s now put out a new CD called Different and the Same, in which he interprets songs by other artists. Weigle’s work has garnered major music-store distribution and raves in Billboard magazine. He won three OutMusic awards in 2003 and was named “Artist of the Month” by the USA Songwriting Competition.

And he’s done it all as an openly gay man who often addresses alternative communities within gay culture—bears, deaf people, cowboys, older men, people with AIDS, and others. With sensitivity and humor, Weigle sings about issues that don’t often show up in music from more mainstream gay artists. He is now working on a fifth album, which will include new songs that address, in his words, “more complex issues in the gay community, like how we treat each other,  healing, and body image.” For more info on Mark Weigle and his music, visit www.markweigle.com.

healing, and body image.” For more info on Mark Weigle and his music, visit www.markweigle.com.

Weigle grew up in a small town in Minnesota, Annandale, with his siblings blaring 1970’s songwriters like Dan Fogelberg and Jackson Browne from the stereo. After a period in Montana he landed in San Francisco, where he now lives with his partner Daniel. I interviewed Mark in person when he was in Boston for a performance late last spring.

— Stephen Hemrick

Gay & Lesbian Review: Let me ask you for a little background on your musical training and early career as a songwriter. Did you start writing music in college?

Mark Weigle: I never went to college! I have a degree from Berkeley in deaf culture and American Sign Language, but I got that much later. Actually, the years that most folks were in college, I was singing in this heavy metal band with hair to my waist and jumping around in spandex. Within a couple weeks of high school graduation, I moved from Minnesota to Montana with the intention of being a park ranger. I’m very into nature and wilderness, as you might have been able to tell from my music. Then I moved back to Minnesota and formed a heavy metal band. We did shows for all ages, rented armories, and put on shows. I wrote the music for the band and so that was sort of a dream come true.

Meanwhile, I was struggling with being gay and not out. Coming out to the band was actually my biggest coming-out step. After that, I came out to my family. Soon I decided I wanted to be more out than the band afforded me, so I cut my hair and I was accepted into New Pacific Academy, a gay activist training school founded by Cleve Jones to train the next generation of activists. In 1990, so many leaders in arts and literature and activism were dying of AIDS in San Francisco, so he brought a hundred young activists there to train the next generation of community leaders. I did seminars with Randy Shilts and Vito Russo and Ginny Apuzzo, and he brought all these friends of his. I met Harry Hay and John Burnside, and Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. It was incredible.

G&LR: It sounds like it. I guess you could say that was the beginning of your activism career.

MW: Yeah. I got a job and worked with Cleve for a while, met my lover, and lived in California. For seven years I was a residential counselor at a crisis shelter for teenagers. And that was a lot of my healing. I got into going to ACA [adult child of an alcoholic]meetings. My mom’s an alcoholic. That was a lot of my healing that turns up in the CDs. And now my music is my activism. It’s where I get to talk about being HIV-positive and to affirm gay men’s self-worth.

G&LR: What are some of your inspirations for your songs?

MW: My older sister in particular was an inspiration for me. Sixteen years older than me, she was a sort of a role model, and very into 70’s singers and songwriters like Dan Fogelberg, Gordon Lightfoot, James Taylor, and Jackson Browne. I started writing songs after I got my first guitar at eighteen, left home, and moved out on my own. “Celebrity” is the first song I ever wrote.

G&LR: How did you get started performing with the band?

MW: The band is actually a relatively recent thing. For several years I’ve toured with solo acoustic kinds of gigs, though the CDs have full instrumentation with bass drums and electric guitars. So since last summer I’ve been touring with a four-piece standard rock-style band with bass, drums, and guitar.

G&LR: When did you decide to start singing about the gay world?

MW: Well, in 1998, I put out my first CD, The Truth Is. I’ve put out a CD every even year since then, until the end of last year. I wrote commercial country music in Nashville and pitched my songs to the country producers, who told me I should become a mainstream country singer. I knew they were assuming that this would mean my going back into the closet and maybe plunking on a cowboy hat. But I already came out once, and I wasn’t about to go back in. So The Truth Is is a reference to that experience, and I decided then to sing about being gay because I am gay.

G&LR: A lot of your lyrics are gay-oriented and concern your HIV status, which is obviously not something you hide. How did you come to the point of immersing those parts of yourself into your lyrics?

MW: Where gay experience is concerned, there are many untold stories. There are tons of gay novels that tell lots of stories, but as far as music goes there are very few of us singing about our experiences. I have a song about a married man having sex for the first time with another man in an adult bookstore booth, a song about a man who lost his partner to AIDS, a song about HIV meds, and one about a former boyfriend of mine who is deaf, and I perform it in sign language. My lyrics developed from wanting to write from a unique perspective about a fresh subject.

G&LR: Are all of your lyrics basically autobiographical?

MW: It’s a mistake when people presume that everything is strictly autobiographical. Like the song “All That Matters” about two elderly men, one of whom makes a reference to World War II, a military burial, and going off to war in ’44. So I’m not sure how people are able to construe that as autobiographical.

G&LR: You look good for your age!

MW: There ya go. As long as people resonate with the story for themselves, how autobiographical it might be is simply extraneous.

G&LR: Since the subject matter of your songs is mostly gay-related, are you specifically targeting a gay audience, or do you hope that this can be a way of reaching out to and in some way educating straight people?

MW: At this point my audience is mostly gay. Part of the reason I perform at predominantly gay venues is out of financial necessity. This is my sole source of income. I used to play at folk festivals and songwriter clubs, and people would come up and tell me how much they loved it, and they’d buy a CD and have me autograph it for their gay brother in L.A. Like, you can’t listen to it cause the lyrics are gay? I can watch The Color Purple and get something out of that. I don’t have to be black to resonate with the emotions in that story. But it seems as if straight folks aren’t ready for the depth of how to explore a gay experience.

G&LR: So is that, in some sense, a failure of the straight world that they’re not able to appreciate a gay artist—unless maybe there’s some kind of campy, maybe slightly puerile humor element?

MW: Yeah, puerile is right. I think straight folks are much more comfortable with some of the more shallow aspects of gay stereotypes, such as those shown on TV shows. I think as the culture evolves to be more comfortable with gay people, straight people will be able to feel a little deeper about our experience and who we really are rather than the campy ha-ha stuff.

G&LR: Do you think there’s anything that you could do to appeal to a larger audience, including lesbians?

MW: Well, the show that you attended [in Boston]was promoted by some local gay men, who really pushed it via bear websites. I call it the fringe of the fringe. My audience tends to be guys in their thirties through their fifties, who either have HIV and/or have really been impacted by HIV and AIDS losses, including bears, rural gays, and gays who are into country music.

G&LR: What’s your definition of a bear?

MW: The PBS show In the Life did a segment on bears, in which one of the interviewees defined a bear as anybody who doesn’t fit the “gay-stream,” as I call it, the self-perpetuated stereotype of the twenty-year-old, smooth pretty-boy with muscles. I appeal to everyone who’s not that. That’s why I’m kind of dismissed by mainstream gay publications and gay pride festivals hiring straight dance divas or for the circuit boys. They don’t really care about my audience. Those whole huge segments of the gay world don’t register enough on their radar.

G&LR: I noticed that you’re nude on the back of one of your album covers, and painted in all the colors of the rainbow on the front. Are you into naturism at all?

MW: Oh, sure I am, whenever possible! The CD art was done by an incredible body paint artist named from San Francisco named Toby Jantzen. He shaved my whole furry body and spent nine hours painting me. He’s not accustomed to shooting partial nudity; he normally does art photography where you can show everything. But this CD was going to be carried in Best Buy and Circuit City, and they’re not into overt nudity. We had to Photoshop my right testicle off the back cover as it is.

G&LR: Oh no!

MW: Yeah, it didn’t hurt a bit.

G&LR: Back to your music. It has a slight country twang and a folksy sound to it. Is that an accurate description?

MW: My first CD is probably more country-folksy. My second one is more pop oriented. In this blurb society, it’s kind of tough, but it has elements of pop, folk, rock, and country. If your definition of country encompasses Lyle Lovett or folks like that, then I’m comfortable with the country label. A lot of people have a pretty rigid stereotype of country music, and while I don’t wear a cowboy hat, I have performed at many rodeos and gay country dances. Like bears or HIV-positive folks, it’s the fringe of the gay-stream, and I’m all about affirming that. It’s a slippery label. On one hand, I don’t want people to reject me based on a stereotype of what country music is, and on the other hand, a lot of people who can’t stand country can really appreciate what I do because I don’t twang. People who love country tend to like what I do because my songs tell stories, which is a hallmark of country music.

G&LR: Would you consider them ballads?

MW: Well, from a songwriting perspective, I’m only interested in telling stories that are fresh or unique, that haven’t been told a million times before. It’s hard to write a basic love song anymore without being stale or redundant.

G&LR: There seems to be a commentary on the state of the gay world right now, and the fact that maybe it’s a little too superficial and body-oriented to appreciate the kinds of meanings and depths that you’re getting into in your music.

MW: I think so. I think our whole culture, our whole society, is so much into consumerism and youth. I have a line in one of my songs, “They tell you you’re broken and then sell you the fix. They create your insecurities, then profit off them.” It’s like, if you have dandruff or bad breath, or not enough muscles, or you’re too fat or too short or too tall, you’ll never be happy or have love, so buy these products and you’ll be fulfilled.

G&LR: It’s a good message that you’re trying to invoke, of self-acceptance and acceptance of all body types and not having to fit a specific mold. Self-acceptance is hard for a lot of gays and something they struggle with a lot of their lives.

MW: Thank you. I get a whole lot of satisfaction, spiritually, from singing to primarily gay audiences, because as gay men we need affirmation. What has kept me motivated to keep doing this are the e-mails and the letters I get from gay men saying, “I lost my lover and your song helped me to remember him,” or “I’m married to a woman and your songs make me feel alive again.” So I don’t think having a primarily gay audience is some second-class status. I agree that straight people would get a lot out of it too if they were willing to allow themselves to feel it, but so far my attempts to reach them haven’t succeeded.

G&LR: You mentioned getting satisfaction spiritually. Are you religious or spiritual?

MW: I’m certainly not religious. Spiritual, absolutely. While the word “sacred” crops up a couple of times in my lyrics, I believe lots of things are sacred by my definition, not some religious institution. The one reference to God in the song “All That Matters” is sung from the perspective of an elderly man whose lover has died. They’ve been lovers for many years, and I was trying to think what would be important to this guy from his generation. It’s definitely from his perspective more than mine.

G&LR: What about the currently raging issue of gay marriage, which some people think is great and more revolutionary types think is not?

MW: I’m not interested in that for myself, but I do want people to have the legal benefits straight people get if they get married. What’s sad to me about gay marriage is it makes me realize that once we have completely equal rights, most of my lesbian and gay brothers and sisters will cease to be activists of any kind. They’re happy to go along with consumerist materialism, which is antithetical to all the things that I think activists should be about.

G&LR: So in a way you’re afraid of gays assimilating into mainstream society and losing touch with their identity?

MW: Yeah. Vito Russo said someday we’re gonna be accepted and understood, and when that day comes, we’re gonna miss the secret world. I’m not interested in fighting for the right to be like everybody else. I’m interested in fighting for the right to be me, to be who I want to be.