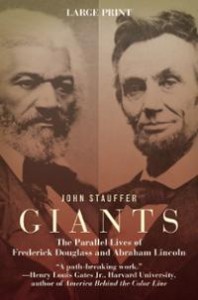

Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln

Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln

by John Stauffer

Twelve. 432 pages,

$30. (paper, $14.99)

“Who Lincoln Was”

by Sean Wilentz

Article in The New Republic,

July 15, 2009

“LINCOLN’S SOUL MATE and the love of his life was a man named Joshua Speed,” John Stauffer writes in his dual biography of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Stauffer refers to carnal love, not to one of those asexual “romantic friendships” in vogue with certain scholars. He chairs the History of American Civilization Department at Harvard; Stauffer’s perspective can’t be easily dismissed as fringe. But that did not deter Sean Wilentz.

Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton, published a gargantuan (25,000-word) review–essay on Lincoln literature in the July 15, 2009, issue of The New Republic. He critiques seven books, including Stauffer’s, that have appeared in tandem with the bicentennial. Wilentz is an elegant writer with an elegant mind. He’s also a mean-spirited crank on various topics, including Barack Obama. Wilentz has a problem with the liberal intelligentsia finding Obama “Lincolnian.” He thinks it’s naïve, misplaced, and just plain wrong; and he might be right. But as he himself admits, the historical verdict is a long way off. Who knows what impends? And in any case, Wilentz shoots himself in the foot when he acknowledges that Obama shares Lincoln’s coolly calculating and opportunistic political style. The similarities don’t end with both being tall, skinny, self-made, eloquent guys from Illinois.

In much the same way that Wilentz objects to the identification of Obama with Lincoln, he objects to Stauffer’s comparison of Frederick Douglass to Lincoln. For example, he dismisses Stauffer’s observation that both Douglass and Lincoln achieved greatness against extremely long odds. America teemed with “self-made” white men, Wilentz insists. Well, yes. But this point detracts not at all from Stauffer’s theme: what could be more remarkable or more inspiring than the fact that a white-supremacist hick, self-educated, and a fugitive slave, also self-educated, ended up playing pivotal roles in the most profound upheaval in American history? Wilentz argues that Douglass had little or no influence on Lincoln’s conduct of the Civil War. He seems by extension to suggest that Douglass had no influence on Lincoln’s long journey to the abolition of slavery. Yet,