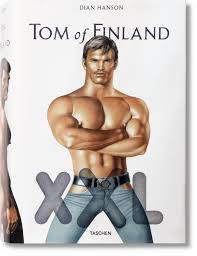

Tom of Finland XXL

Tom of Finland XXL

Edited by Dian Hanson

Taschen Books. 668 pages, $200.

ANYONE who’s even casually acquainted with Tom of Finland’s work knows that, for Tom, size was everything. The frolicking gay men in his pictures are always well-muscled, often to absurd proportions. Invariably, they sport either impossibly large bulges in their pants or, better yet, titanic, tree-trunk-thick erections that defy the laws of physics. So it’s altogether fitting that the new Tom of Finland book just published by Taschen is as much a physical monument to the legendary gay artist as it is a study of his work.

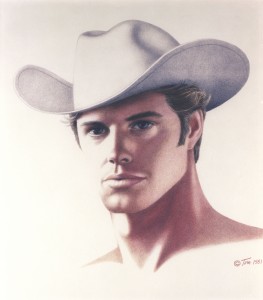

Consider the dimensions: measuring roughly thirteen by nineteen inches and three-and-a-half inches thick, the nearly 700-page volume weighs in at about fifteen pounds. No doubt the artist would be proud of these proportions, and of the fact that carrying it home from the bookstore provides something of a workout. Fortunately the publisher has packaged this gargantuan tome in a box equipped with a plastic handle. (And this isn’t Taschen’s first Tom of Finland book, having published one other monograph and even a small-scale mini-boxed set.) Tom of Finland, who was born Touko Laaksonen in Finland in 1920 and died in 1991, did much to redefine the gay male identity. If that claim seems at all suspect, editor Dian Hanson makes a good case for it through a series of essays by the likes of art critic Edward Lucie-Smith, literary critic Camille Paglia, and fashion designer Todd Oldham, among others. These writings, along with the reproductions of Tom’s work, help illuminate the artist’s life, development, and importance to gay culture. Other writers have chronicled Tom of Finland’s life and work in greater detail than this volume. Micha Ramakers’ Dirty Pictures: Tom of Finland, Masculinity, and Homosexuality (2000), for example, is an entertaining and accessible analysis of the artist’s contributions. Valentine Hooven’s 1993 biography provides a full picture of Laaksonen’s development into Tom of Finland. But the essays collected by Hanson, many of them quite brief, provide a wonderfully diverse set of perspectives. Lucie-Smith succinctly traces Tom’s artistic development and explains the cultural confluence that helped his work resonate so powerfully. When his first published drawing appeared in Physique Pictorial magazine in 1957, the McCarthy-era view of homosexuals as feminine and weak but potentially subversive still prevailed. Tom, as Lucie-Smith notes, “revived the spirit of Walt Whitman” and celebrated the strength, power, and wholesomeness of gay love as both beautiful and masculine. This coincided with the emergence, among other things, of the California bodybuilding culture and also the valorization of the leather-clad biker outlaw as epitomized by Marlon Brando’s performance in the 1953 film The Wild One. In depicting gay male sexuality with such jubilance, Tom “encouraged and participated in the creation of a distinctive and separate gay male culture.” Paglia’s essay takes the analysis even further. In addition to doing her part to put forth a more generous assessment of Tom’s place in art history than many others have offered, Paglia notes that Tom’s frequent play with top-bottom role reversal helped subvert gay stereotypes and that his work advanced the cause of gay liberation. Words like “liberation” and “freedom” pop up often in these essays. Todd Oldham, Armistead Maupin, John Waters, and Holly Johnson (of “Frankie Goes to Hollywood” fame) offer personal accounts of how Tom of Finland opened their eyes to the celebration of male beauty and figured in the formation of their own gay identities. Of course, any artist who depicts sexuality of any kind with such assertiveness invites controversy. A scan of the index of Ramakers’ study of Tom’s work reveals a litany of things that Tom has been accused of—Nazism, racism, and promoting the patriarchy, among others. Truth to tell, it’s easy to understand the charge that Tom’s work glorifies fascism. Uniforms are everywhere, and Tom’s scrapbooks (of which selected pages are reproduced in the Taschen volume) contained pasted-in photos of German soldiers and officers. Although Tom fought heroically for Finland in World War II, he was clearly fascinated by, and attracted to, German soldiers—but for sexual rather than political reasons. Indeed, as Durk Dehner notes in two essays in the book, Tom avoided discussing politics and was deeply conflicted about his wartime experiences, two of which Dehner discusses briefly. One was a series of clandestine encounters with a handsome German airman who was killed soon afterward in an air battle. Another was Tom’s shock, upon turning over the body of a Russian paratrooper he had just bayoneted, at beholding one of the most beautiful faces he had ever seen. Both of these experiences haunted him, but they also informed his explorations of the sexual possibilities of military regalia. Reading anything more into the uniform pictures risks missing the point. Tom’s depictions of black men, and of women, have also generated a fair share of commentary. Hanson’s essay, “Tom’s Woman,” offers a rejoinder to the idea of “Tom’s Man” and describes the infrequent (but by no means nonexistent) portrayals of straight and bisexual encounters, and their attendant power structures, in Tom’s work. With respect to racial politics (a topic not addressed at length in any of the essays), Tom was clearly fascinated with black men, and there are many depictions in his work of biracial romps. The book even includes at least one picture of a black man topping a collared-and-leashed Asian. Perhaps the most loaded image, as it were, is Tom’s fanciful drawing of a Caucasian hunk ramming his member into the planet Earth as he holds it in place with his hands. Yes, this can be read as an inherently imperialistic and patriarchal image, but in the end, as Paglia reminds us, Tom’s work is really about boundless fertility. As an artist, Tom of Finland was certainly prolific. He created an estimated 4,000-plus sketches, drawings, paintings, linocuts, and pastels. Of these, some 1,200 finished works and 1,500 studies have survived. Hanson has arranged a representative sample of these by decade, with detailed captions for each in English, German, and French. She also includes a fascinating section of Tom’s rarely seen “lost” works. This book helps secure the reputation of an artist who has clearly found his place not only in gay culture, but in art history as well.