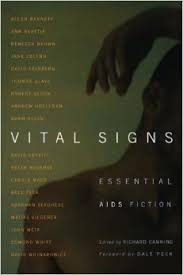

Vital Signs: Essential AIDS Fiction

Vital Signs: Essential AIDS Fiction

Edited by Richard Canning

Carroll & Graf. 352 pages, $15.95

WHEN DID WE STOP thinking about AIDS? Was it when the combination drug therapies started to keep people alive? Or when the epidemic shifted to the third world with a magnitude difficult to grasp in any personal way? Or when we became engaged in other battles, for gay marriage, against global warming? The AIDS epidemic in America, first mentioned in the New York Times in July 1981, is now part of history. In this book, Richard Canning, who teaches courses about AIDS literature to college students, has assembled eighteen short stories, written at what he calls “the epidemic’s darkest time of unknowing,” the early 1980’s through 1998. What is startling about these stories, especially for readers who lived through that era, is not how distant but instead how familiar they seem.