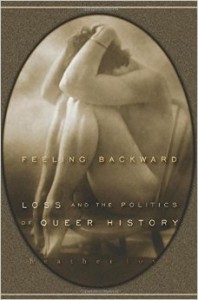

Feeling Backward: Loss and Politics of Queer History

Feeling Backward: Loss and Politics of Queer History

by Heather Love

Harvard University Press

163 pages, $39.95

Feeling Backward is a scholarly treatment of queer theory that assumes some knowledge of conventional literary theory. In it, Heather Love makes the argument that we have feelings in common with those who came before us, but early practitioners of queer theory have ignored the effects of oppression on our literature.

Establishing her thesis in a thirty-page introduction, she attacks the issue from several angles in exhaustive detail. She then moves on to investigate the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the lives and writings of four authors: Walter Pater, Willa Cather, Radclyffe Hall, and Sylvia Townsend Warner.