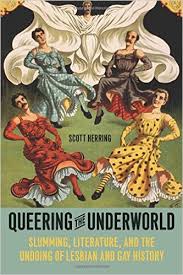

Queering the Underworld: Slumming, Literature, and the Undoing of Lesbian and Gay History

Queering the Underworld: Slumming, Literature, and the Undoing of Lesbian and Gay History

by Scott Herring

University of Chicago Press

278 pages, $25.

THIS SPRIGHTLY, informative book does a rare thing: it covers entirely new territory in gay literary studies. Queering the Underworld concentrates on the intersection of the fin de siècle phenomenon of “slumming”—that is, taking the bourgeois reader into the urban demimonde—and the emerging expression of gay and lesbian sexual identities. While there’s no intrinsic logic to restricting himself to American sources, Herring persuades us that his study gains clarity and perspective through such a specific prism. Both canonical authors and the marginalized suitably take their place. Among the former are Djuna Barnes and Willa Cather, whose story “Paul’s Case” (1905) has become a familiar reference point in queer fictional scholarship (Judith Butler, Jonathan Goldberg, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, et al.). Here, however, it is given new life by being considered in light of Cather’s close—and not always sympathetic—interest in Oscar Wilde’s trials and travails. A contrast to her own sturdy, masculine prose style is found in what Cather calls the “driveling effeminacy” of Robert Hichens’ satirical novel on æstheticism and Wilde, The Green Carnation (1894). Much more to her taste was Wilde’s peer, the “vagabond” poet Verlaine, as Max Nordau had labeled him in his notorious 1892 breviary Degeneration.v