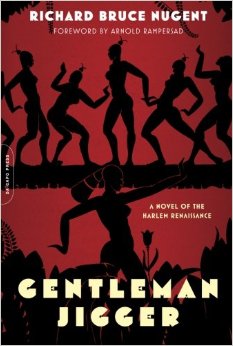

Gentleman Jigger

Gentleman Jigger

by Richard Bruce Nugent

Da Capo Press. 352 pages, $16.95 (paper)

RICHARD BRUCE NUGENT, one of the youngest members of the Harlem Renaissance, and the only openly gay one, seems poised for his own literary renaissance. More than twenty years after his death, Gentleman Jigger, which Nugent wrote in the waning days of the Roaring Twenties and the early years of the Great Depression, has finally been published, thanks in great part to Nugent’s literary executor and editor Thomas H. Wirth. Wirth reminds us that the vexed expression “gentleman jigger” is a “sardonic riff on an old racist ditty” and implies mixed racial heritage. Wirth’s indispensable Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent (2002), which contains an excerpt from Gentleman Jigger, was reviewed in these pages (Nov.-Dec. 2002), and Nugent appeared on the cover of a recent issue (Jan.-Feb. 2008).

Gentleman Jigger is a dialog-heavy novel, with the character Stuartt (correctly spelled)—clearly a stand-in for Nugent, who was in his early twenties when he wrote it—represented as the most fabulous artist and delightful person that one could hope to meet. With characters whose real-life counterparts can often be easily discerned (and others for whom Wirth helpfully provides a key), Gentleman Jigger’s first half is a breezy, sometimes sarcastic, retelling of carefree days full of wild parties, gin-soaked nights, and exceedingly hung-over mornings at 267 West 136th Street in Harlem, the rooming house where he and his platonic friend Wallace Thurman lived.

It was Thurman (who’s called Rusty in Gentleman Jigger) who dubbed it “Niggerati Manor.” He was working on Infants of the Spring (1932) at the same time as Nugent was writing his opus, and it remains unknown to this day which parts of these romans à clef were stolen from the other. Their friends, acquaintances, and hangers-on were all writers, artists, and bon vivants connected to the Harlem Renaissance. They read Firbank, Proust, and Apollinaire, drank Ganymedes, danced the “mess around,” and sometimes had serious discussions about racial identity and prejudice, often causing discomfort to Thurman’s lover Bum, who had become “one of the clique.” In real life, he was Harold “Bunny” Steffanson. Except for the 1920’s slang, their arguments sound entirely contemporary.

Near the end of the first half of the novel, Stuartt moves away from Harlem to Greenwich Village to educate himself in the ways of hustling and to follow his love objects, who are for the most part Italians and often gangsters. Throughout, Nugent writes very openly about his (or Stuartt’s) sexual escapades, and sometimes one forgets how long ago he was writing, especially when he, Bum, and Rusty talk about hoodlums and rough trade.

In Part Two, the setting moves to Chicago, where Stuartt falls in love and has an affair with a mobster named Mario Orini. Wirth identifies Orini as probably being based on Lucky Luciano. Stuartt’s attraction to gangsters leads him into several dangerous liaisons, but he also has time to fall in love with a debutante with the unlikely first name of Wayne. Stuartt and Wayne are often in society’s spotlight with Orini and his moll, Bebe. Rather more hurried than the first half of the novel, the book ends with Stuartt becoming a major success on stage, as a costume designer, and as an artist. (In real life, he was an artist and dancer, touring for two years with Porgy and Bess). An outing of an entirely nonsexual sort appears in the last pages and makes one wish that Nugent had continued his writing career.

It should be noted that Fire!! A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists—in which Nugent’s “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” famed as being the first openly gay-themed short story by an African-American writer, appears—was reprinted and is available at a very reasonable cost. It includes an insert, dated 1982, in which Nugent describes his early years and Wirth offers comments on the growing importance of Fire!! in the late 20th century.