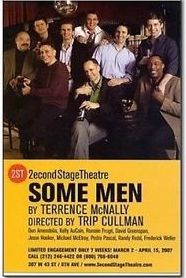

Some Men

Some Men

by Terrence McNally

Second Stage Theatre, New York

“I WANT to kill myself sometimes when I think I’m the only person in the world and the part of me that feels that way is trapped inside this body that only bumps into other bodies without ever connecting with the only person in the world trapped inside of them,” Johnny agonizes in Terrence McNally’s Frankie and Johnny in the Claire de Lune (1987). “We gotta connect. We just have to. Or we die.”

The life-or-death importance of human interconnection, and the insecurities that create hindrances to satisfying relationships, are at the heart of McNally’s dramaturgy. “I cannot hear through walls or … partitions!” Chloe complains in Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991), having spent the play asking of her husband in the next room, “Did you say something?” Similarly, in a recurring gag in A Perfect Ganesh (1993), two American travelers in India are exasperated to discover there’s no one on the line whenever they answer a constantly ringing telephone. Yet one of the most moving moments in McNally’s Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994) occurs when six gay men, outlandishly dressed in tulle and feathered headdresses, rehearse the “Pas des Cynges” from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake for an AIDS benefit. As the men cross arms, join hands, and dance en pointe across the stage, they parodically re-enact the medieval Dance of Death, a reminder of the universality of mortality. In McNally’s appropriation of the motif, however, the men’s forming of a community in the face of death becomes an emblem of the love, valor, and compassion with which gays might negotiate the terror of AIDS (this was before protease inhibitors).

“Only connect,” one man in a gay chat room volunteers to another in McNally’s new play, Some Men (which completed its limited run in New York in late April and is certain to become a staple of the regional gay theater circuit). Unfortunately, his correspondent’s recognition of gay novelist E. M. Forster as the source of the quote fails to guarantee a bond between the two men. The play, which is a series of vignettes of American gay life from 1922 to the present framed by the events at a gay wedding, readily admits to the difficulties of finding a satisfying relationship: sexual chemistry may not be present when other elements of attraction are; personal insecurities such as a fear of so cial disapproval or a reluctance to limit oneself to just one sexual partner become barriers to engagement; gay self-loathing proves a bell jar that suffocates the most promising relationship. Thus, in one of the play’s most poignant scenes, a 1930’s Harlem club performer narrates his relationship with a self-loathing composer that resulted in the song “Ten Cents a Dance.” And in one of the play’s most hilarious scenes, a pair of Queer Studies majors from Vassar is offended to learn that a long-married couple did not feel oppressed in pre-Stonewall America (“It was different then. We didn’t make so much of a fuss. … We just wanted to be happy”).

cial disapproval or a reluctance to limit oneself to just one sexual partner become barriers to engagement; gay self-loathing proves a bell jar that suffocates the most promising relationship. Thus, in one of the play’s most poignant scenes, a 1930’s Harlem club performer narrates his relationship with a self-loathing composer that resulted in the song “Ten Cents a Dance.” And in one of the play’s most hilarious scenes, a pair of Queer Studies majors from Vassar is offended to learn that a long-married couple did not feel oppressed in pre-Stonewall America (“It was different then. We didn’t make so much of a fuss. … We just wanted to be happy”).

McNally’s dramaturgy in Some Men reveals an even more subtle form of connection in what seems initially to be a pastiche of loosely connected, historically organized scenes but turns out to contain multiple connections unanticipated by the audience. Bernie, a closeted gay man who came out to his wife in the 1960’s and whose journey to self-acceptance is mapped across several scenes, turns out to be the grandson of the Irish immigrant chauffeur whose Depression-era relationship with his financier employer was dramatized earlier in the play. The hustler with whom Bernie had his first gay sexual experience appears in a later scene as the guest of a supposedly homophobic athletic club member, suggesting that the man’s virulently anti-gay comments are a mask for his own repressed desire. Later in life, the hustler becomes an influential Milton scholar who dies of AIDS and proves to have been a close friend of the men interviewed by the self-righteous Vassar undergraduates (one of whom subsequently attends a group therapy session where he awkwardly confesses his attraction to an older AIDS activist). The black partner of Bernie’s son mentions an uncle who owned a nightclub in 1930’s Harlem. And another participant in the gay therapy group mentions a drag queen uncle whom the audience recognizes from a scene set on the night of Stonewall. Thus, far from living separate, disconnected lives in different cities and decades, the “some men” of the title function as colored pieces of glass in the constantly changing kaleidoscope of modern gay life: names and circumstances may differ, but a desire for connection makes us one.

Stumbling into a piano bar on the night of Stonewall, an outspoken drag queen from Long Island named Archie (a.k.a. “Roxie”) confronts the divide that exists between gay men who wear “Shetland wool and musk oil” and those who dress as women. Catching herself answering one form of prejudice with another, Archie ponders: “We live in these little personal boxes and we break free only to find ourselves in a bigger box. I can break free for the rest of my life and still be in a box.” Before leaving to join his fellow drag queens rioting in the street, Archie sings a haunting a cappella version of “Over the Rainbow” in honor of the late, lamented Judy Garland, in the process framing the conundrum addressed by McNally’s play. Gays may break out of one box by winning the legal right to marry, but as important as it will be to celebrate and protect such a form of connection, marriage will not be a panacea. Rather, we’ll simply find ourselves facing new, increasingly more complicated problems in our relationships. This, McNally poignantly suggests, is the paradox of the ongoing struggle to connect: relationships promise a kind of happiness that seems present but remains maddeningly just beyond our reach—somewhere over the rainbow. Forever eluding us yet leading us perpetually forward, the hope of connection dares us to discover a state that is, in the words of one of the play’s characters, “beyond marriage.”

Raymond-Jean Frontain is the editor of Reclaiming the Sacred: The Bible in Gay and Lesbian Culture.