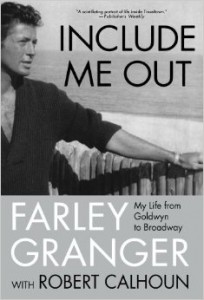

Include Me Out: My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway

Include Me Out: My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway

by Farley Granger

with Robert Calhoun

St. Martin’s Press. 272 pages, $26.95

IN THE PROLOGUE to his memoir, Include Me Out, Farley Granger recollects how, in December 2004, he was invited to a Luchino Visconti retrospective at the Brooklyn Academy of Music to view a restored print of Senso, the lavish 1958 melodrama in which he starred as an Austrian deserter who feigns love for a married Venetian countess and leads her into disrepute and an operatic act of revenge. Noting that he had only previously seen a butchered 1968 version of the film, cut to fit into a 90-minute format for TV, and that he was never comfortable watching himself on screen, Granger adds: “As the audience applauded at the film’s conclusion, I found myself applauding with them. Not only had I enjoyed Senso as much as they had, but I was also proud of the performance of that young actor playing Franz Mahler. For the first time in my life, I realized that in the time I had spent making films between my first movie, The North Star, in 1944, and Senso, in 1954, I had become an actor.”

Granger’s book is subtitled “My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway,” as if to remind readers that his life had a full and creative second phase in the theatre after a career primarily on screen. Co-authored by the actor’s life partner, Robert Calhoun, the book recounts how Granger was discovered and nurtured as a teen by the legendary Samuel Goldwyn, went on to work with top-notch directors Lewis Milestone (The North Star) and Nicholas Ray (They Live by Night), and, after including himself out of his contract, went to Italy to work with Luchino Visconti. The memoir’s title is an homage to the movie mogul’s notorioius malapropisms (or, Goldwynisms, as they came to be known).

In an amusing chapter entitled “The Gorgons,” Granger offers his shrewd depictions of Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons, Tinseltown’s gargoyles of gossip. Hopper is described as a pixilated and maternal harridan and Parsons as a bilious bitch with a psychological axe to grind. At one point Hopper advises the ingénue Granger to avoid leftist associations, reflecting the anti-communist sentiments in Hollywood that would eventually flare into the Red Scare and the McCarthy witch hunts. “Before I could say anything, she whipped off her blouse, revealing her naked shoulders and a white bra. I had never heard a woman, except my mother, swear before, especially one in her bra, with a hat like that, sitting behind a desk. ‘What the hell is Sam doing making a damn Commie movie?!’ she suddenly shouted at me.”

Like many actors in Hollywood past and present, Granger was compelled by the studio to keep his gay proclivities under a tight rein, and he admits that he didn’t have sex with anyone until his stint in the Army Special Services Unit in Hawaii. This unit was under the command of the classical actor Maurice Evans, who put together plays and arranged entertainments for all the troops in the Pacific. Long before “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” Granger was working in tandem with a homophobic and resentful macho Navy lieutenant named Chuck Garvin, who “didn’t believe that a ‘bunch of fags prancing around on a stage’ had anything to do with morale.” One can imagine what Garvin thought the “pansies” were up to in their unit, but Granger claims that “no one ever did anything remotely suggestive” while working, notwithstanding the amount of makeup worn by Major Evans’ private secretary.

Granger loses his virginity to an island sex worker named Liana after a few rum and Cokes. This is followed by a passionate tryst with “a very handsome lieutenant commander” named Archie who’s a dead ringer for Sterling Hayden. “Before I knew it, we were in the bedroom and out of our clothes.” Although they promise to get together “when this mess is over,” a reunion isn’t in the cards.

Referring to “liberal” Hollywood’s long-engrained tradition of homophobia, Granger observes the following:

I found it difficult to answer questions about “gay life” in Hollywood when I was living and working there. … I was never ashamed, and I never felt the need to explain or apologize for my relationships to anyone. I had many gay friends, but more of my friends were straight and most married with families. The ratio of my gay to straight friends was probably in direct proportion to that of gay to straight people in all aspects of the film business and society in general. I have loved men. I have loved women. I will talk with affection and without guilt or remorse about both in this book.

Although Granger’s career began in the 1940’s and 50’s, when movie moguls still groomed and engineered the public personae of their stable of contracted players, he bridles at one point when called on the carpet by a studio functionary about being seen in public with Aaron Copland, who had scored the first film he appeared in, 1944’s The North Star, directed by Lewis Milestone. Informed that Copland was a “known homosexual,” Granger replied “So what!” and pointed out that Copland was a major composer whose private life should not be a matter for gossip or speculation.

Long before the Church of Scientology became the refuge of last resort for movie stars intent on kicking away the traces of a queer past, the studios’ public relations departments worked overtime picking up the scattered hairpins, planting lead soles in the loafers, and supplying “beards” for their players. Granger recalls his studio-manufactured fan magazine romance with June Haver, and points out how MGM’s Van Johnson, although a homosexual, “worked nonstop and soon became the darling of the bobby soxers,” yet was continually pressured by Louis B. Mayer to get married “in order to protect his all-American image.” Johnson then married a recently divorced starlet and came out of the experience “relatively unscathed, at least in the gossip columns.” There are also backstage tales about numerous celebrities, including the bisexual heart-throb Tyrone Power, the omnivorous Leonard Bernstein, and Rope writer Arthur Laurents, with whom he had a brief affair. He also had a wild frolic with Barbara Stanwyck, endured a polite brush-off from Noël Coward, and spent a romantic night with Jean Marais aboard his houseboat in Paris.

After he appeared in Nicholas Ray’s film noir, They Live by Night—for which the publicity poster refers to his character as “Just a kid who’s seen too much of the crooked side of life and not enough of the straight”!—Goldwyn loaned Granger to Warner Brothers to work with Alfred Hitchcock in the director’s first color film Rope, based on the notorious Leopold and Loeb case, in which two students who are ostensibly lovers commit the “perfect murder” for the intellectual thrill of it all. Next, Granger would be cast in Hitchcock’s “criss-cross” suspense film, Strangers on a Train, based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, in which the director ingeniously casts him as the star tennis jock, Guy Haines, against Robert Walker’s campy gay psychopath, Bruno Anthony.

Having grown up and worked on the venal lots of Hollywood, Granger was attracted to Broadway and the chance to strengthen his acting ability in the theatre. After buying out his contract, Granger moved to the Big Apple, “around the corner from Bloomingdale’s, which to my Los Angeles eyes was the choicest store I had ever been in.” When Luchino Visconti failed to get Marlon Brando for the lead in Senso, a film that uses Italy’s Risorgimento as its historical background, he approached Granger for the role. Although the latter had never heard of the Italian director, he agreed upon learning that Tennessee Williams was involved in the project.

The last third of this memoir is devoted to Granger’s considerable work in theatre and television, where he starred with Julie Harris in The Heiress, waltzed with Barbara Cook in the 1960 first revival of The King and I at City Center, toured in the National Repertory Theatre with the legendary actress (and “outspoken lesbian”) Eva LeGallienne in classics such as The Crucible, The Seagull, and Hedda Gabler, and appeared in Deathtrap and Lanford Wilson’s Talley & Company, with the Circle Rep, for which he won an Obie Award. In short, this is a memoir that will prove compulsive reading to old movie buffs as well as those who are fascinated by the inner workings of Hollywood.

Michael Ehrhardt is a freelance writer and journalist based in New York City.