Published in: November-December 2006 issue.

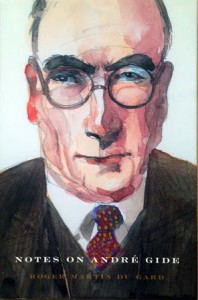

Notes on André Gide

Notes on André Gide

by Roger Martin Du Gard

Helen Marx Books. 99 pages, $14.95

ACCURATELY TITLED, Notes on André Gide is a fragmentary memoir about Gide by a close friend who offers new insights into the great French novelist and essayist whose nonfiction book Corydon was the first defense of homosexuality in modern times. The close friend, Roger Martin Du Gard, an important French writer in his own right, begins his memoir in 1913 with the words: “At last I have met André Gide!”